US election: America the beautiful's ugly election

- Published

US election: Relive the wild ride in 170 seconds

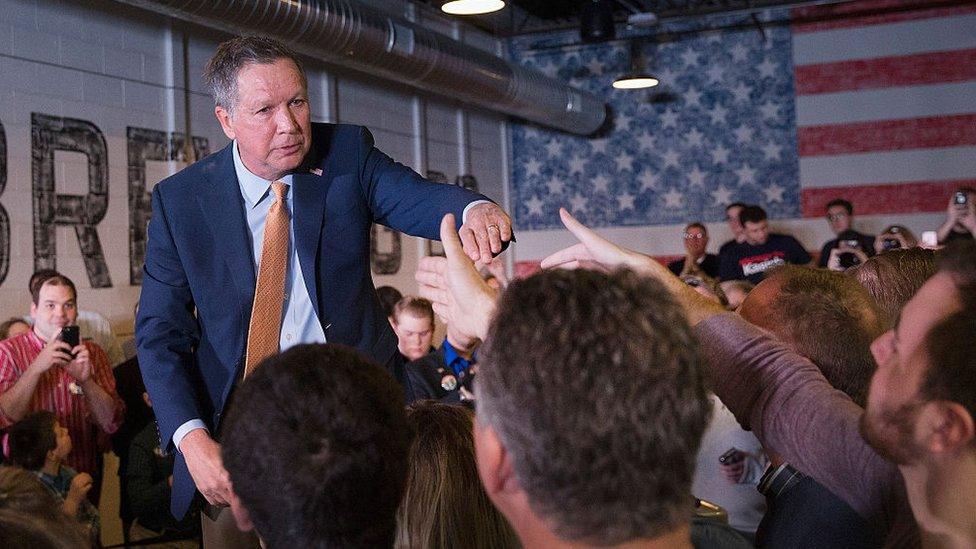

Some of the wisest words I have heard during this campaign came from the Governor of Ohio and Republican presidential hopeful John Kasich.

During a campaign stop at a brewery in Michigan, he explained how he had implored young aides, during a picturesque swing through the upper peninsula of the Great Lake State, to avert their eyes from their smartphones and to take in the scenery passing by unnoticed outside.

Though sometimes it meant coming late to the newest Trump Twitter storm or reading the freshest batch of Clinton campaign emails a few minutes after Wikileaks released them - an eternity in this age of hurtling news cycles - I have tried to heed his advice.

For the landscape of America is not just a wonder to behold, but always provided clues to this election.

John Kasich had some words of advice that Nick Bryant took to heart

The post-industrial wastelands of the rustbelt, with their skeletal remains and carcass-like old steel mills, are hardly a new feature of the topography in states like Pennsylvania and Ohio. But to view them again was to look at the seedbeds of Trumpism - rubble-strewn but seedbeds nonetheless.

In New Hampshire, especially when we visited some of the state's pretty university campuses, it was impossible not to notice the Bernie Sanders signs dotting the snow-covered lawns and verges. In Florida, ahead of Super Tuesday, it was the absence of Marco Rubio placards and the proliferation of Make America Great Again signage that pointed towards a Trump victory.

US election: The essentials

More recently in the suburbs of Philadelphia, the home to many soccer moms, security moms and Starbucks moms, demographics that often have the decisive say in presidential elections, it was the surfeit of Clinton/Kaine markers.

Had we not been looking outside the window as we drove away from Pittsburgh airport one morning, we would have failed to notice the signpost to Clinton, Pennsylvania.

Down that road, greeting drivers as they entered, was a mammoth Trump/Pence billboard, which stood in towering defiance of the name of this small hamlet, and conveyed the message that Clinton was Trump country.

US Election: Voters in Pennsylvania sound off

Just this past weekend, had our eyes been trained on our smartphones as we drove through the steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, we wouldn't have seen the long queue stretching around the block.

Knowing that these people could not be queuing to cast their ballots, since Pennsylvania doesn't have early voting, we stopped to see what was happening. We found out they were waiting in the damp cold for food handouts.

Many of these working people, inevitably, were supporting Donald Trump, even though none of them could ever afford to stay at one of his hotels or play a round at one of his golf courses.

Indeed, the rule of thumb in this election, in non-urban settings especially, was the more impoverished the landscape, the more likely its inhabitants were to support the billionaire.

Yet this election hasn't only provided a lesson in geography, physical and political. Teachable moments have come in all manner of forms. We've had to study again the fast-changing demographics of the American electorate.

For years we've been talking about the mounting importance of the Hispanic vote, and it is clear already from early voting that this sleeping giant has awoken. In Florida, the Clinton campaign estimates it has increased by 139% over four years ago.

The multi-ethnic make-up of this nation of immigrants could end up being decisive. Indeed, just as a sign hung in the Clinton campaign headquarters in 1992 declaring "It's the economy, stupid," this year it could easily read "It's the demographics, stupid."

Because it is weighted so heavily in the Democrats' favour at present, the Electoral College, the state-based mechanism by which Americans elect their presidents, is also key.

This is primarily because many of the most populous states, like California, New York, Illinois and Pennsylvania, are reliably Democratic. They form part of the famed "blue wall" - 18 states, plus the District of Columbia - that have voted Democrat in the past six elections.

Election 2016: The race for battleground states

If recent history repeats itself, those states alone would give Hillary Clinton 242 Electoral College votes. If she won Florida, and its 29 electoral votes, she would bust through the 270 mark needed to win.

Understanding Electoral College mathematics is essential for any campaign reporter, but I wonder how many correspondents have, like me, checked the rules in Nebraska and Maine, the only states that are not winner-takes-all. Another teachable moment.

There have been others. Since most of us modern-day journalists like to try our hands at psychiatric portraiture, I have tried to learn more about narcissistic personality disorder.

Many commentators from both sides believe having a basic grasp of the condition was important in making sense of the behaviour of Donald Trump. It also came in handy when the disgraced former congressman Anthony Weiner made an unexpected cameo at the end.

On the psychiatric front, I've also learned more about co-dependency or relationship addiction. Defined as "an emotional and behavioural condition that affects an individual's ability to have a healthy, mutually satisfying relationship," it neatly described the media's relationship with Donald Trump.

Covering Hillary Clinton raised the fascinating question of what feminism means for millennial women, many of whom have been singularly unenthused by the prospect of a first female president.

And as with Trump, her personality is endlessly intriguing. Why, for instance, does she struggle to convey the warmth and spontaneity in public that many of us have witnessed in private? Trump, too, can ooze charm when you meet him one-on-one.

Because of the criminalisation of American politics, and, more specifically, the FBI's investigations into Hillary Clinton's private email server, we've all had to brush up on our jurisprudence. If this election turns out to be disputed, maybe we will have to become quickly versed again in US constitutional law, as in 2000, although one can only hope that this year's contest will be decided by voters rather than jurists dressed in black robes.

Because of the "celebritisation" of American politics, the blurring of the lines between pop culture and political culture, we've all had to try at least to keep pace with the zeitgeist.

Katy Perry (Roar), Pharrell Williams (Happy) and Rachel Platten (Fight Song) have provided much of the soundtrack, but I confess that the most memorable musical moment of the campaign came for me when Donald Trump entered on the night of the Empire State primary with Frank Sinatra's thumping anthem, New York, New York, bouncing off the marble walls of Trump Tower.

That night I made the mistake of trying to record what we call a piece to camera while the billionaire was delivering his victory speech.

Blessed with a booming voice, in an atrium that doubles as an echo chamber, for a few seconds my words came close to overpowering his. Thinking he was being heckled, Trump stopped mid-stream, as his security and press team converged on my red-faced cameraman and me.

On other occasions, when Trump harangued the press in a thuggish and abusive way, I would happily have ejected myself from Trump Tower.

This has been an ugly and dispiriting campaign. All the more reason to look out the window at the landscape.

But what of the people who inhabit this great land - the voters who decide this election?

The commonplace has it that a country gets the politics it deserves. But as we reach the end to this absurdly long and costly process, my sense and profound belief is that America is better than this election.