President Trump: Seven ways the world has changed

- Published

With Donald Trump in the White House, the US's relationship with the rest of the world has changed in some important ways. Here are seven of them.

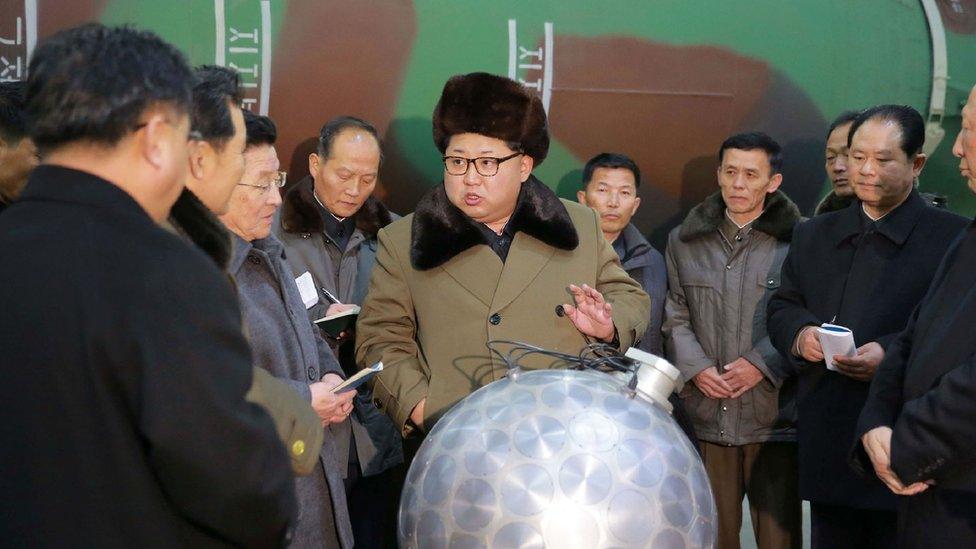

Heightened nuclear tensions in Asia

Donald Trump still has to decide how to handle this man - Kim Jong-un

A Donald Trump presidency has raised major security questions in Asia.

Not only did he shock China with comments on Taiwan before his inauguration, but his Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has spoken of blocking China's access to artificial islands it has been building in the South China Sea, prompting warnings of a "military clash" from a state-run newspaper.

Japan and South Korea have both been singled out by Mr Trump for relying too much on the US. He has even said they would benefit from having their own nuclear arsenals.

Then there is the region's renegade state, North Korea, which is currently developing its own nuclear weapons.

Mr Trump faces the task of curbing those ambitions, something that has eluded successive US leaders.

Under President Obama, the policy was called "strategic patience" - squeeze North Korea with sanctions, persuade others to do the same, particularly China, and wait it out.

But Mr Trump's Vice-President Mike Pence has now said the "era of strategic patience is over".

The administration says "all options are on the table" and Mr Trump's announcement that he was sending an "armada" of US warships towards the Korean peninsula raised the spectre of military action.

The move was met with defiance from North Korea's regime, which threatened "weekly" missile tests and warned of "all-out war".

But there was increased confusion just 10 days later when it emerged that the US Navy strike group, which Mr Trump said had been deployed towards the Korean peninsula, instead travelled in the opposition direction.

While the White House clarified the whereabouts of the ships and insisted they were on their way, Mr Trump returned his focus to pressuring China to take action.

"China is very much the economic lifeline to North Korea so, while nothing is easy, if they want to solve the North Korean problem, they will," he tweeted.

His next step is unknown, but the early attempts of this unpredictable president in tackling the world's most unpredictable state have already exposed a flashpoint that is likely to return in years to come.

Relationship with Russia even more complicated

Russian President Vladimir Putin has praised the incoming US president and the feeling is mutual

During the US election campaign, Mr Trump praised Russian President Vladimir Putin as a strong leader, with whom he would love to have a good relationship.

That was before US intelligence agencies determined Russia was responsible for hacking Democratic Party emails during the campaign - a conclusion that Mr Trump eventually conceded he agreed with.

The explosive publication of an unverified dossier alleging that Russia holds compromising material on Mr Trump has also raised prickly questions for him. He has batted them away, dismissing the allegations as "fake news".

But concerns over his administration's ties with Russia continue to dog his presidency, with his national security adviser Michael Flynn abruptly resigning over conversations with Russia's ambassador in the weeks before inauguration.

Mr Trump said he wanted to start off trusting President Putin but warned "it might not last long at all".

And it seems it didn't. The relationship appeared to take a sharp downward turn following a chemical attack in Syria, which was blamed on the Syrian government, and Russia's continued support for President Bashar al-Assad.

President Trump went on to say the US "may be at an all-time low in terms with our relationship with Russia". He said it would be a "fantastic thing" if the nations improved ties, but warned "it might be just the opposite".

Greater focus on Nato

The US president has reversed his condemnation of the defence alliance Nato

Mr Trump has previously been hugely critical of Nato (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), a cornerstone of American foreign policy for more than 60 years.

He attacked the organisation as "obsolete" and characterised its members as ungrateful allies who benefit from US largesse.

Defence Secretary James Mattis warned Nato members in February that Washington would "moderate its commitment" if members did not meet his boss's demand that they raise their defence spending to 2% of their GDP.

Mr Trump claimed his tough talk was causing the "money to pour in", although analysts point out that countries were already increasing their contributions under a 2014 agreement.

But during a joint press conference in April, Nato chief Jens Stoltenberg thanked the US president for his attention to the issue. "We are all seeing the effects of your strong focus on burden sharing in the alliance," he told him.

Meanwhile, Mr Trump had a change of heart and said Nato was "no longer obsolete".

He said the threat of terrorism had underlined the alliance's importance and called on members to do more to help Iraqi and Afghan "partners".

Use of force

The moment the MOAB bomb struck the IS cave and tunnel system

President Obama was elected to end America's wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and was extremely reluctant to get involved in another conflict in the Middle East.

Even when the scale of atrocities in Syria became brutally clear, he remained convinced military intervention would be a costly failure.

Instead the Obama administration focused on providing humanitarian aid, giving some funding to moderate Syrian rebels and promoting a ceasefire and political negotiations aimed at President Assad's departure.

Donald Trump was also previously opposed to US military action in Syria, calling for greater focus on domestic policies. "Forget Syria and make America great again!" he tweeted, external in 2013.

So it was quite a turnaround when the president ordered US missile strikes on a Syrian government airbase in April.

He said the chemical attack blamed by the Syrian government had changed his attitude. "That attack on children had a big impact on me," he said.

The missile strike was the first time the US had directly targeted the Syrian regime since the conflict began, and viewed as a breathtaking policy shift for a previously isolationist leader.

But it was just days until the Trump administration flexed its military muscles once again, this time hitting Islamic State militants in Afghanistan with a weapon known as the "mother of all bombs", or MOAB, that had never been used by the US in combat before.

And with greater US defence spending on the table, the US appears - at least for now - to be taking a more forceful role in foreign conflicts.

Future of free trade uncertain

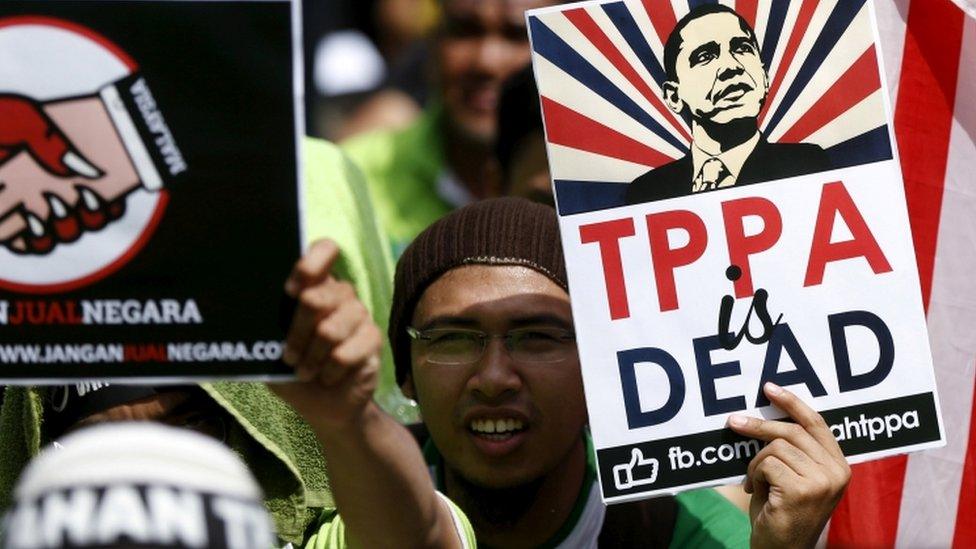

There has been strong public opposition to free trade deals

With his trade policies, Donald Trump has embarked on bringing about the biggest change to the way the US does business with the rest of the world for decades.

He has threatened to scrap a number of existing free trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement between the US, Canada and Mexico, which he blames for job losses. He has even suggested withdrawing the US from the World Trade Organization.

Since winning the election, he has focused on threatening companies, particularly automobile makers, that he will slap a tariff of 35% on goods manufactured in Mexico.

How far he will get with this is still unclear.

But on his first day in office, Mr Trump abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a 12-nation trade deal brokered by President Obama and representing 40% of the world's economic output.

The deal had yet to be ratified by a divided Congress, but Mr Trump's executive order withdrew US participation altogether.

The thrust behind his trade policy is to create jobs in the US, close the trade deficit, and get "good deals" for Americans.

Already he has targeted the country's foreign worker visa programme and ordered a review of waivers in free-trade agreements to see whether they allow foreign firms to undermine American companies in the global government procurement market.

However, he has rowed back on a campaign promise to label China a currency manipulator - a move that experts warned could have provoked a trade war.

Climate change rethink

Mr Trump has promised a renewed push to use coal across the US

Mr Trump had said that he would "cancel" the Paris Climate Agreement, external within 100 days of taking office. This has not happened and his senior advisers are now reportedly divided on whether it should.

He has, however, made large strides in his pledge to reverse climate change regulations introduced by President Obama.

He signed an executive order in March that reversed the Clean Power Plan, which had required states to regulate power plants, but had been on hold while being challenged in court.

The president said the order was necessary to ensure US energy independence and jobs. But environmental groups warned that undoing the regulations would have serious consequences at home and abroad.

Mr Trump has repeatedly denied the science of human-caused climate change, describing it as "fictional'.

Like many issues, however, he has expressed conflicting views, telling the New York Times in November that he acknowledged there was "some connectivity" between human activity and climate change and saying he would "take a look at" the Paris agreement, rather than having already decided to pull the US out of it.

Even if he wanted to do that though, the US remains legally bound to the Paris plan for four years.

Climate change: Nations will push ahead with plans despite Trump

There are also "legal and procedural roadblocks" which would inhibit Mr Trump from a complete overhaul of US climate policy, The New York Times says.

But critics say his stance could cause other reluctant governments sceptical about the issue to reduce their efforts to cut planet-warming emissions.

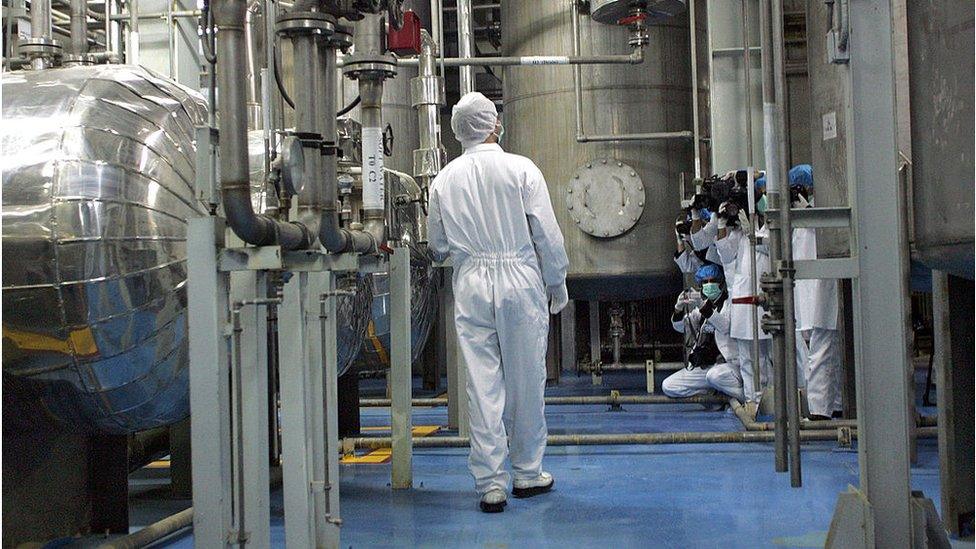

Iran nuclear accord in doubt

The Iranian nuclear accord was the "worst deal I think I've ever seen negotiated", said Mr Trump

For President Obama, the deal that saw sanctions against Iran lifted in exchange for guarantees it would not pursue nuclear weapons was a "historic understanding".

But for Donald Trump, echoing Republican concerns, it was "the worst deal I think I've ever seen negotiated".

He had said dismantling it would be his "number one priority" but had not specified what he wanted to do.

Now his administration has announced a review of the whole US policy towards Iran. This would take in not only Tehran's compliance with the nuclear deal but also its actions in the Middle East where it is a key player in the Syrian conflict and a rival of Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Already Iran's Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has urged Trump to stay committed to the nuclear deal. He previously suggested the US would have to respect the accord given that it was thrashed out with several world powers.

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has been more blunt. "If they tear it up, we will burn it," The Associated Press quoted him as saying.

Relations to the countries did not get off to a good start after the Trump presidency began - the US placed new sanctions on Iran after it conducted a ballistic missile test.

"Iran is playing with fire," President Trump tweeted.

- Published15 December 2018

- Published15 October 2020

- Published6 July 2017

- Published9 November 2016

- Published10 September 2024