US election 2016: The Trump-Brexit voter revolt

- Published

US voters have delivered a blow to the political establishment by electing outsider Donald Trump to the presidency, much like UK voters did earlier this year when they opted to leave the EU. But just how close are the parallels between Tuesday's result and June's referendum? Were the voters who gave Mr Trump his victory much the same as those who voted to leave the EU?

For many on this side of the Atlantic, there was a strong sense of deja vu on Tuesday night as it gradually emerged that Donald Trump has pulled off a dramatic victory.

It all seemed reminiscent of the drama that British voters had experienced when in the small hours of 24 June it became apparent that a majority had voted to leave the European Union.

One reason of course was that neither result had been expected. In the UK most - though not all - polls put Remain narrowly ahead. In the US most - though again not quite all - polls put Hillary Clinton narrowly in the lead.

Read carefully, neither set of polls could in fact be said to point to a clear winner, but most commentators had convinced themselves that Remain and Mrs Clinton respectively would emerge victorious.

But another arguably more important reason for the sense of deja vu was the similarity between some of Donald Trump's key campaign messages and those of the Leave campaign.

UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage says he 'couldn't be happier' about Mr Trump's victory

Both majored on concerns about immigration. Both questioned whether the existing global financial order necessarily benefitted the ordinary man in the street. And both portrayed themselves as the underdogs campaigning against an allegedly complacent and out of touch political establishment.

In the UK these stances have been shown to appeal in particular to the so-called "left behind", that is, voters who feel they have lost out economically in recent years and who are uncomfortable with some of the social changes that have been going on around them.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump was remarkably successful in such mid-West Rust Belt states as Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin, where the decline of manufacturing industry has seemingly created a part of America that can also be said to have been "left behind".

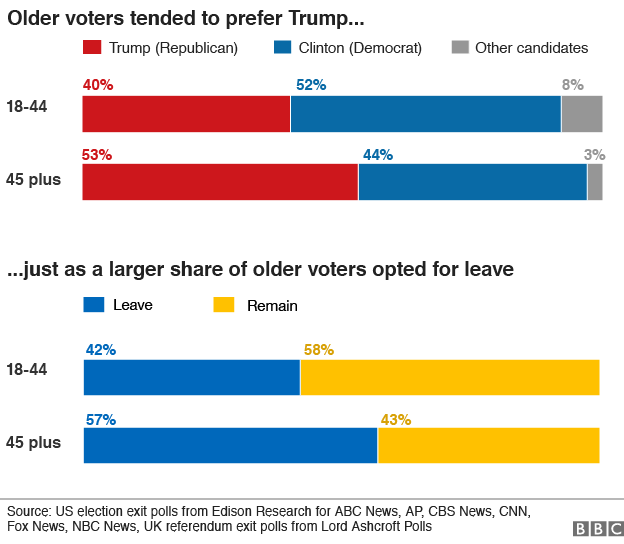

There are certainly some striking similarities between the UK and US voting trends. To begin with, older voters in the UK were inclined to vote to leave the EU, whereas a majority of younger voters were in favour of remaining, according to exit poll data. Similarly, in the US Mrs Clinton was ahead among younger voters, while Mr Trump was more likely to be preferred by older citizens.

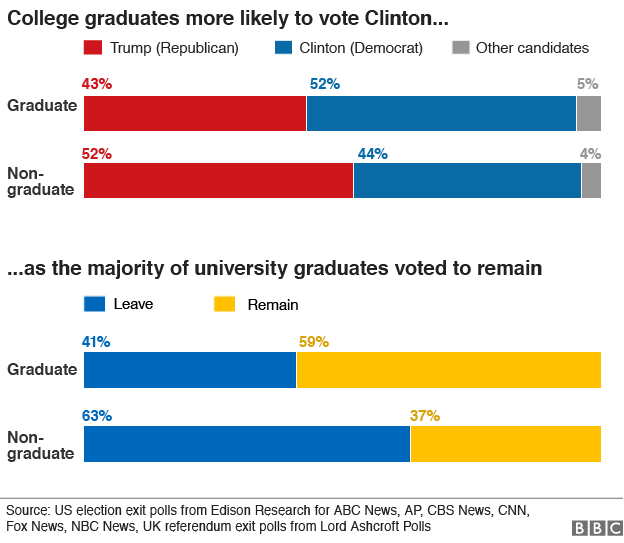

At the same time, an educational divide was apparent in both ballots. In the UK, polls suggested a majority of university graduates were keen on remaining in the EU, while those without a degree voted to leave. Equally, in the US, exit polls indicate college graduates were more likely to vote for Hillary Clinton, whereas those who were not college graduates inclined towards Donald Trump.

Most young UK voters wanted to remain in Europe

Moreover, this educational divide was one of the most remarkable features of the US election. Republican candidates do not usually do better among non-graduates than graduates.

In 2012 the level of support for the then-Republican standard-bearer, Mitt Romney, was almost exactly the same in the two groups. Here perhaps is the strongest evidence that Mr Trump's campaign messages had a particular resonance for a certain section of the US population that might also be described as "left behind".

However, perhaps the analogy should not be pushed too far. A closer look at graphic above reveals that the education divide in the EU referendum was rather sharper than that in the US election.

In the UK the gap was wide - around three-fifths of graduates voted to remain, while 63% of non-graduates cast a vote for leaving. In the US it was more nuanced - only just over half of college graduates voted for Mrs Clinton and only just over half of non-graduates backed Mr Trump.

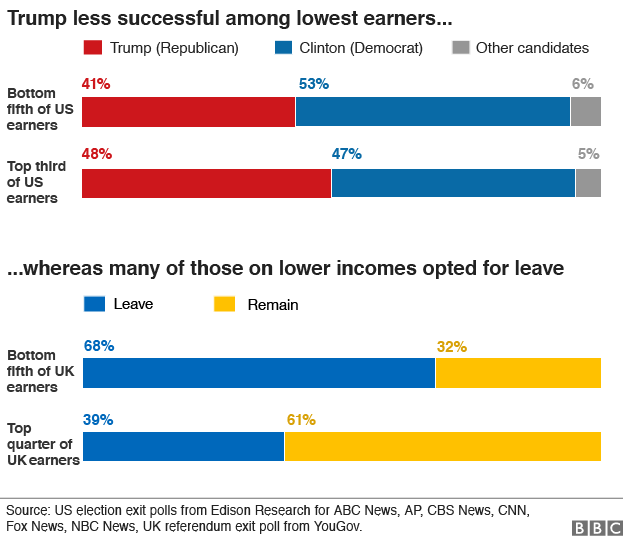

Moreover, in other respects the claim that it was the "left behind" who took Mr Trump to victory does not match the evidence. In the UK those who voted to leave often had few, if any, educational qualifications, but also tended to be on lower incomes. Around two-thirds of those with incomes of less than £20,000 ($25,000) a year voted to leave, while around three in five of those earning more than £40,000 ($50,000) backed staying in the EU.

But Mr Trump was not particularly successful among low-income voters. In fact, just over half of those with incomes of less than $30,000 (£24,000) voted for Mrs Clinton. Conversely, those on more than $100,000 (£80,000) a year only preferred Mr Trump by the narrowest margins.

Mr Trump's campaign messages may have enabled him to reach out to voters with few, if any, qualifications for whom social issues such as immigration are often a particular concern. However, it appears he was less successful at mobilising support among those who might be thought to be economically left behind.

There are other parallels between the vote in the US and that in the UK too, though in the case of the US at least they reflect political differences that long predate Mr Trump.

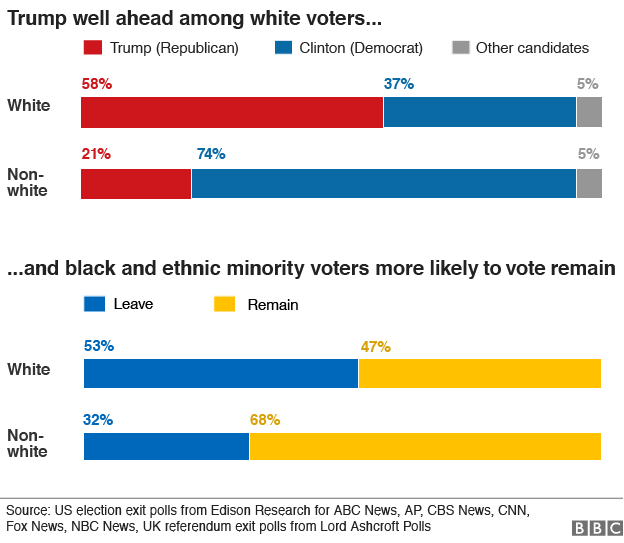

Hillary Clinton was more popular among the US's increasingly diverse population

The Republican president-elect was well ahead among white voters, but trailed Mrs Clinton heavily amongst the remainder of America's increasingly diverse population. In the UK too, black and minority ethnic voters were disinclined to vote to leave, put off perhaps by the Leave campaign's focus on the issue of immigration.

Meanwhile, evangelical Protestants once again turned out for the Republican nominee in very strong numbers, while those who do not profess any religion at all voted heavily for Mrs Clinton.

In the UK, too, those who do not claim to belong to any religion - a much larger group than in the US - were inclined to vote to remain. However, the religious divide in the UK largely reflects the fact that younger voters are more likely not to claim some kind of religious identity, rather than having much to do with their religious outlook itself.

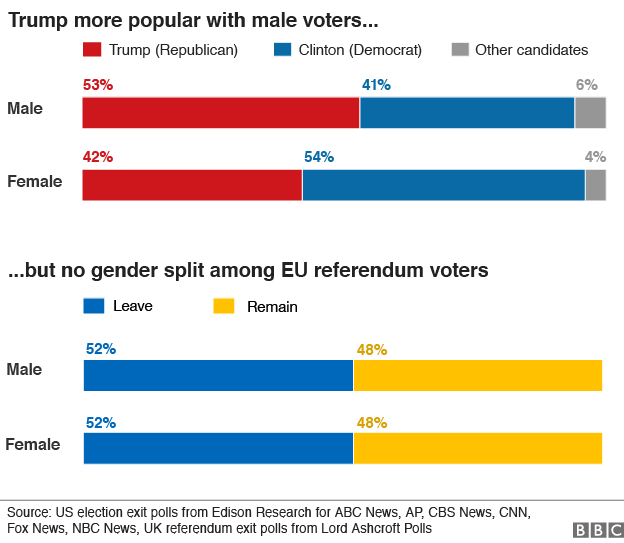

US elections have also long been marked by a gender difference, with women being more likely to vote Democrat, men to support the Republicans. That, too, was also in evidence on Thursday.

That was one divide that was not evident at all in the UK referendum - men and women voted in much the same way. It seems that Mr Trump still has much to learn from UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage and Leave campaigner Boris Johnson, now UK foreign secretary, when it comes to wooing women voters.

John Curtice is Professor of Politics, Strathclyde University and ESRC Senior Fellow, The UK in a Changing Europe programme