US election 2020: Lives that could be reshaped by Supreme Court

- Published

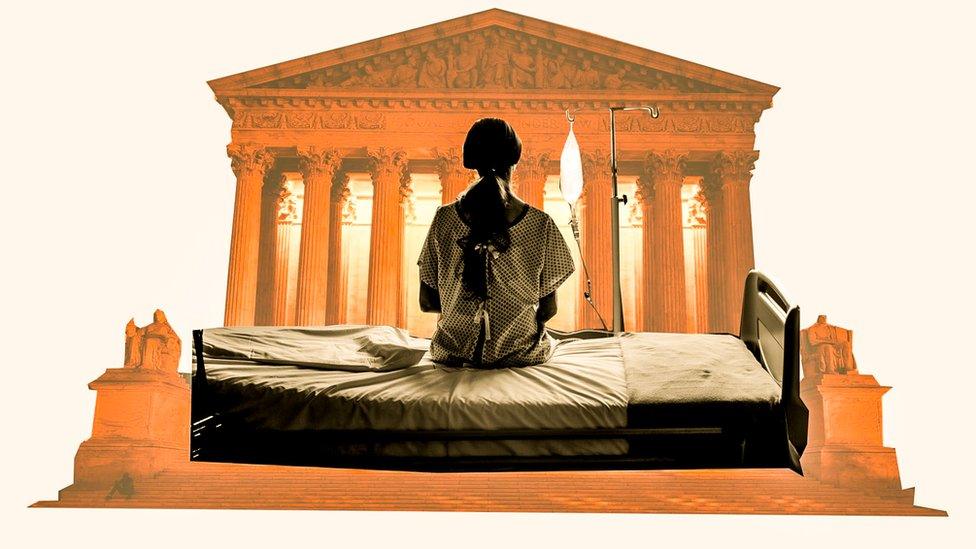

The US Supreme Court considers President Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act on 10 November. There are tens of millions of Americans whose access to healthcare could drastically change as a result of their ruling. Here are their stories.

Allie Marotta has heard the tales of people giving up their dreams in exchange for a job which provides health insurance. She says the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is why she's been able to still pursue hers.

Diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 2006, Marotta describes it as a "fatal illness that's made chronic by the use of medication". Without access to insulin, death takes a matter of hours. Marotta also has celiac disease - a common autoimmune combination.

Marotta says she couldn't have entered the performing arts industry in New York City without the ACA's provision allowing children to stay on their parents' plans until age 26. After the pandemic hit, she's struggled with work, but is still able to access health coverage.

"In my community, no one has health benefits for a job because performing arts is all independent contractors and freelance," she notes, adding that she's helped many friends navigate the marketplace system.

It's the same story for gig workers, restaurant staff and those in hospitality across the country. But in the years since its enactment, prices for many marketplace plans have risen to hundreds of dollars per month. Marotta says when she aged off her parents' coverage in December, she couldn't afford to pay for the plans she qualified for under the ACA.

"It's already so flawed, and this is the only crumb you're willing to give the American people," Marotta says. "It was already difficult for me to access the ACA, and you're taking that away?"

What is the point, she wonders, of a health system that only works for the healthy?

The ACA brought health insurance coverage to millions of Americans when it was signed into law back in 2010. It was a campaign promise of candidate Donald Trump's to repeal and replace it but he's been unable to do that so far in his first term.

The Trump administration's work to dismantle the act has now culminated in a question of its constitutionality. Next month, it'll be before a conservative Supreme Court, with President Trump's third justice Amy Coney Barrett potentially on the bench, and it's uncertain what its fate may be.

Here are the terms to know...

Obamacare: A nickname for the Affordable Care Act

Pre-existing conditions: Any health conditions diagnosed before signing up for an insurance plan (like diabetes, cancer, asthma, pregnancy)

Individual mandate: The requirement that people buy health insurance or pay a tax penalty; the unpopular penalty was repealed by Republicans in 2018

Medicaid: Free healthcare service programme for low-income Americans

The marketplace: State-run insurance websites (in the style of online shopping) where you can compare plan prices

The Supreme Court will rule on whether the act's individual mandate that everyone must buy health insurance is in line with the Constitution.

If the mandate is a no-go, then the court must also decide if the rest of the act can limp on as things are - or if it's unconstitutional in entirety. If it's the latter, protections for patients with pre-existing conditions, federal subsidies and aid expansions for lower-income Americans are also gone.

To Republicans, the ACA represents a drastic, expensive move into socialist healthcare - one that increases costs but lowers the quality of care. And national health spending did increase from $2.6tr in 2010 to $3.65tr in 2018, though the act wasn't entirely to blame.

It's also been unpopular among already-insured Americans who saw their coverage costs rise as sicker individuals were added to the pool. Some conservatives also view the act as an overstep of the federal government, an intrusion into the doctor-patient relationship.

The real question, of course, is how the row over fine print in Washington translates to a bottom line for patients.

Out of the 23 million Americans who are currently insured by the ACA or expanded Medicaid programmes, 21 million could lose their insurance if the act is overturned. Down the road, more could drop their plans if a lack of federal subsidies sends insurance prices sky-high.

And the backdrop to all this - a global pandemic that's affected more than 7.5 million Americans. Given the damage Covid-19 can do to the body, and the unknown number of related complications it may cause survivors, contracting the virus in 2020 could become a pre-existing condition in the eyes of insurers down the road.

Shana Ziolko is 36 years old, a local city government worker just outside of St Louis, Missouri, and is afraid.

On the ACA now, it costs Ziolko, whose preferred pronouns are they/them, a week's pay each month for insurance that ensures they have access to the doctors and prescriptions they need to treat long-term kidney problems and bipolar disorder.

A better job, with better benefits and economic security was the plan - Ziolko finished graduate school in December. Then the pandemic hit.

"If [the ACA] got repealed, then I would spend one week just paying for medication instead of paying for insurance," Ziolko says. "I'm going to be afraid to go to a doctor for anything."

Ziolko says the ACA allows them to have insurance - but it means a lot more than that.

"I don't have to miss work because I'm sick and I'm avoiding a doctor. I am functional because I have my medications," Ziolko says. "It makes my current life possible."

A Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) analysis found that as of 2018, nearly 54 million non-elderly adults in the US have pre-existing health conditions that would have made them uninsurable before the ACA.

A 2017 government study, external reported about 133 million Americans under age 65 would have to pay extra for insurance coverage - or be denied outright - due to a pre-existing condition if the ACA is overturned. That's close to half the US population, with conditions ranging from obesity to substance abuse to Alzheimer's.

To be clear - most people in the US are insured through their employers.

But when insurance is tied to a workplace, what happens when you lose or change jobs, or need to retire early? What about starting your own business or working part-time gigs? What happens if you get a divorce?

While President Trump has promised to protect pre-existing conditions in particular, his justice department has been arguing in court that the entire ACA ought to be overturned.

Trump did sign an executive order to safeguard pre-existing conditions, but a policy statement - even if it's from the president - doesn't legally bind insurance companies.

Fifty thousand dollars. That's how much a two-night hospital stay could have cost Rachel Delgrego's family if they'd been uninsured. Delgrego's mother has an autoimmune condition that's seen her in and out of hospitals over the last five years.

While her father was working, health coverage wasn't a concern.

"Now that my dad has retired, it's even more stressful," the 22-year-old says. "He's 67 now and did not want to retire. He didn't know what type of insurance he was going to have after retiring."

It's "scary", she adds, to think about how quickly the bills could add up if the ACA's protections are taken away. Her parents have been setting aside money from retirement to have a fund in case her mum's health gets worse.

Rachel Delgrego (centre) and her parents

Delgrego, too, faces uncertainty. Her asthma would count as a pre-existing condition in a post-ACA world. She lives in a working-class suburb outside of Philadelphia, and says many of her friends are also struggling with affording healthcare - particularly when the jobs available don't offer benefits. It's made healthcare her main concern as a voter.

"They can debate and turn this into a political issue all they want, but it's not political when you see your mom in a hospital bed," she adds.

Six in ten Americans, external say they or a member of their family have a pre-existing condition.

Polls this summer found 49% of the US views the ACA favourably (42% do not). But pre-existing condition protections are backed by both party supporters and independents. The majority of Americans - 72% - place high importance on keeping those protections in place.

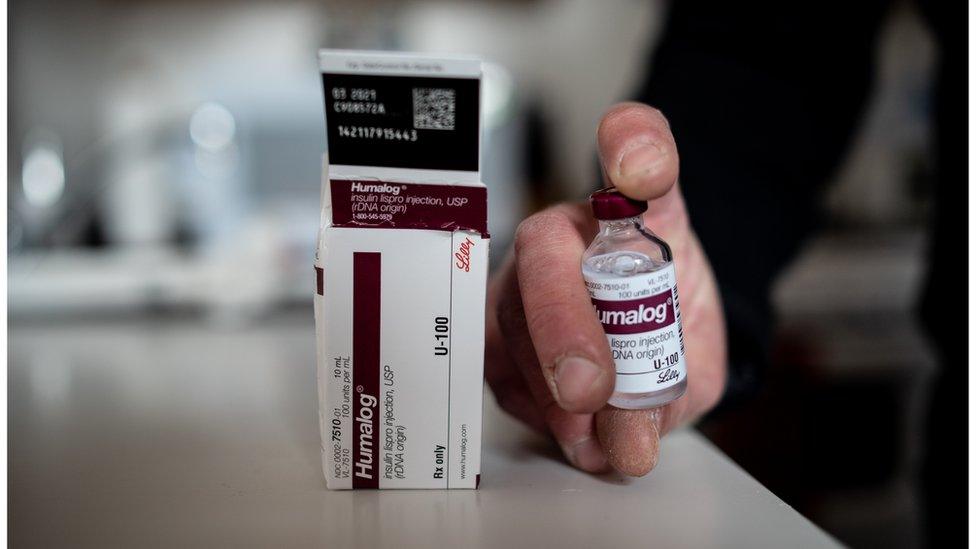

Laura Marston with her insulin pump

For type 1 diabetes advocate Laura Marston, the thought of returning to a pre-ACA world is "ridiculous" because without insurance supplied by her employer, affording insulin would be a struggle.

She is particularly concerned about young, chronically-ill people who have graduated into a pandemic-distressed economy.

"They're already at a disadvantage and then thinking that ACA protections could be taken away? That would mean, practically speaking for someone like me… with a minimum of three vials [of insulin] a month, that's almost $1,000 a month. If even one person has to pay that, it's not fair."

She is frustrated that both establishment Republicans and Democrats seem reluctant to move America towards more accessible healthcare. Backtracking to protect industry profits while removing the penalties on healthy people and then trying to keep those with pre-existing conditions covered, she says, isn't feasible.

"The math just doesn't work," says Marston. "It's not magic, folks."

From her experience, anything short of a law addressing the issue - as the complete ACA sought to - won't cut it.

The status quo may not be perfect, but it's clear that for patients on the frontlines of the coverage crisis, going back is not an option.

- Published15 August 2019

- Published2 May 2019

- Published14 March 2019

- Published14 September 2016

- Published10 October 2018

- Published26 June 2020

- Published29 March 2019

- Published13 September 2017

- Published17 October 2018