US election 2020: What the US election will mean for the UK

- Published

If you want to see one of the great monuments to what is called "the special relationship" between Britain and the United States, take a stroll to Grosvenor Square, a leafy haven in the heart of London.

There you will find a grand statue of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the great wartime American president, set high on a stone pedestal, dominating the square. Below it there is a surprise, an inscription revealing that the statue, unveiled in 1948, was paid for by "small sums from people in every walk of life throughout the UK".

Think of it: at a time of grim post-war austerity and food rationing, 160,000 Britons were so admiring of America they were willing to pay five shillings each - about 8 pounds in today's money - to erect a statue in memory of its former president.

This memorial marks perhaps the zenith of US-UK relations. It is doubtful today many Britons would fork out hard-earned cash to raise a likeness of Donald Trump.

A survey last month by the Pew Research Center found only 19% of Britons have confidence in Mr Trump to do the right, external thing in world affairs. Transatlantic relations over the past four years have been ragged.

President Trump publicly criticised Theresa May's Brexit negotiations; on Twitter he accused British intelligence of spying on him; down the phone he shouted at Boris Johnson about the UK's approach to the Chinese tech giant, Huawei.

There have been "ups and downs at a political level", the ever-diplomatic Lord Sedwill, Britain's recent national security adviser, told the BBC. "President Trump is a very unusual occupant of that office."

President Barack Obama meeting Prince George at Kensington Palace in London in 2016...

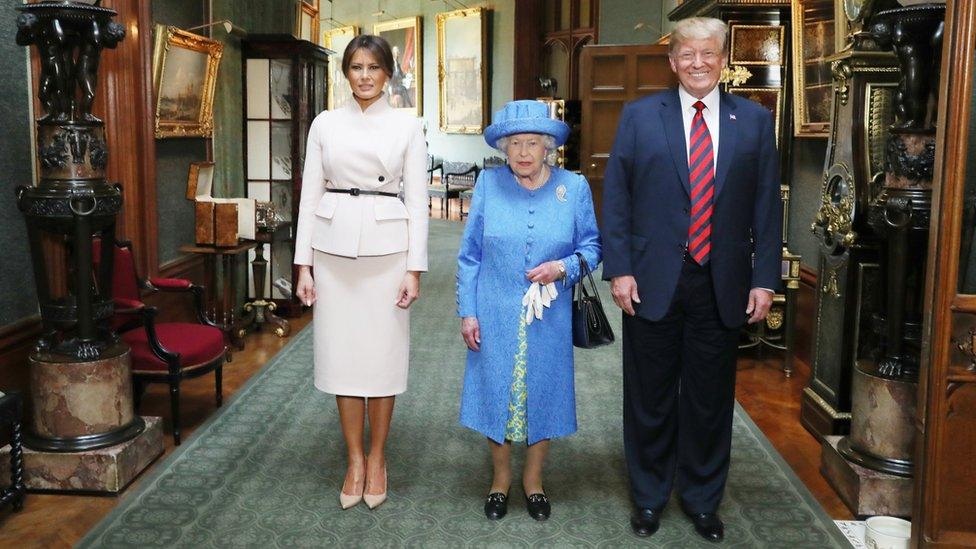

And Donald Trump and his wife Melania meeting the Queen at Windsor Castle in 2018

Of course, the official relationship between Britain and the US endures; the military, diplomatic and intelligence links that run deep into the fabric of both nations.

But the occupant of the White House shapes that relationship, and that is why the election on November 3 matters.

The big question about a second Trump term is whether he would double down, unconstrained by electoral concerns, or moderate his behaviour as he looked to his legacy.

Some reckon there might just be more of the same. For the UK, that would mean reasonably warm personal relations at the top between the president and a prime minister he once called "Britain Trump". There would be more positive noises about Brexit and a future trade deal. But there would likely also be more disputes over policy such as relations with China or Iran.

In terms of substance, the big unknown is whether Trump mark 2 would withdraw the US even further from the defence alliance Nato. In recent interviews, John Bolton, Trump's former National Security Adviser, has said there was real risk of this.

Others say it would be resisted by the US political establishment. But if the US did step back from Nato, Britain and the rest of Europe would have to spend more on their own defence and that could mean substantial tax rises.

On Iran, a second Trump administration would push harder for the collapse of the deal Tehran agreed to curb its nuclear ambitions. Britain would come under more pressure to split from European allies or risk tougher US sanctions that apply indirectly to British businesses and banks. The transatlantic divide on this and other issues would likely grow if Mr Trump gets four more years.

If Joe Biden were to win, the US would be less hostile towards the international organisations that Britain values so much, such as the United Nations. It would try to repair global partnerships. He's promising a "summit of the democracies". Transatlantic relations would be easier, less unpredictable, with fewer unexpected tweets.

Relations between the US and the UK over some policy issues would improve. Take climate change. Next year Britain is hosting a big UN summit - known as COP26 - where it is hoped the world will agree new carbon reduction targets. President Trump, who pulled the US out of the previous Paris climate accord, is unlikely to help get a deal, whereas Mr Biden has promised to re-join Paris and push for even more ambitious targets.

Both Mr Biden and Mr Johnson share a tough approach towards Russia. They are closer on China, agreeing on the need to challenge malign behaviour but also allow for engagement on global issues. Divisions over Iran may become less stark as Mr Biden has promised to re-engage with the nuclear deal.

That is not to say a Biden presidency would not pose difficulties for the UK.

He is not a natural fan of the prime minister, describing him last December as "a physical and emotional clone" of President Trump. He strongly opposed Brexit. And as someone with a strong sense of his Irish heritage, Mr Biden has expressed concern about the potential impact Britain's departure from the European Union could have on Ireland's economy and Northern Ireland's security.

Presidential candidate Joe Biden outside Downing Street in 2013, when he was vice-president

Many analysts believe a Biden presidency would shift its focus towards Germany and France, seeing them and the EU as America's primary transatlantic partners.

Sir Peter Westmacott, former UK ambassador in Washington, said: "Biden will lean towards Paris and Berlin not because he has anything intrinsic against the UK, but because we will count for less in Washington because of Brexit. Our importance to the US has always been linked to the difference we can make to US interests in Europe, and vice versa."

Regardless of who wins on November 3, many observers believe some trends will continue: the gradual US retreat from global leadership and military intervention as the country rediscovers its isolationistic instincts. Mr Biden might be more internationalist in outlook than Mr Trump, but he too is promising to end US involvement in "forever wars", focus his foreign policy on improving the lives of America's middle classes, and protect US jobs from the tide of globalisation.

According to Sophia Gaston, director of the British Foreign Policy Group, that means Britain will come under pressure to fill that vacuum and defend the multilateral organisations that have served the West so well.

"Even if Biden wins," she says, "Britain is going to have to take a bigger role in those international institutions and a bigger role in leadership on issues like climate change, democracy and human rights because the US president is going to be more concerned by a fractious domestic landscape."