A harsh reality in coal country - with or without Trump

- Published

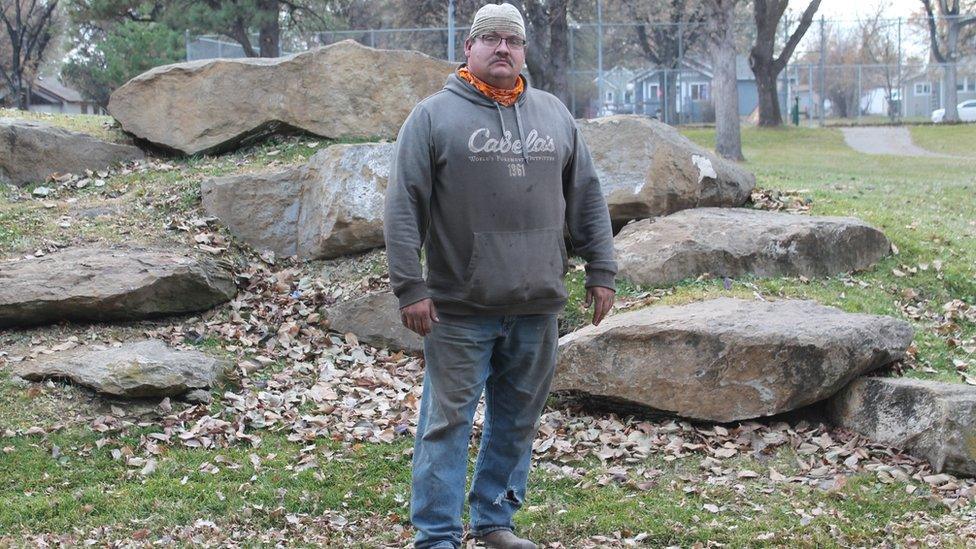

Boilermakers Anthony Grimes, Jason Small and Ryan Hunter outside the Colstrip power plant

Colstrip, Montana, has been a poster child for the kind of coal mining community that looked to Donald Trump to bring back the industry and save their town. But four years later, on the eve of a Joe Biden presidency, the only thing that's clear is that saving coal - and Colstrip - was never going to be that simple.

On Wednesday, 4 November, the day after a US presidential election without a definitive winner, Jason Small sat on the darkened patio of the Whiskey Gulch Saloon contemplating his own unclear political future. Under an inky sky dotted with stars shining with a brilliance only possible in far-flung towns like this one, Small's phone screen lit up his face as he scrolled the latest voting results.

"I think the precincts that have no numbers back are going to be heavily in my favour," he said. "I'm not wanting to call it early because you just never know."

Small - who is anything but, standing 6ft 4in tall with a barrel chest and a booming voice - was up several points in his bid for a second state senate term representing four counties in south-eastern Montana, including two Indian reservations. As a member of the Northern Cheyenne Nation, he is somewhat of a political anomaly, one of just a handful of elected indigenous politicians who are Republican. His opponent in the race was another Native candidate, a Democrat.

"There's a lot of misguided views about Republicans hating Native Americans and stuff like that. And that's not the case," he said. "I've been one heck of a liaison."

Senator Jason Small

That evening, Small was still dressed in a sweatshirt, smudged jeans and work boots having come straight from an 11-hour shift at the coal-burning Colstrip Power Plant, a massive green and tan edifice whose four smokestacks loom over the town. Not long after he arrived at the Whiskey Gulch, two of his fellow boilermakers joined him for a beer. All three supported Donald Trump for re-election. With chagrin, they had been watching the news that Joe Biden was inching towards 270 electoral votes.

"With Joe Biden and Kamala Harris getting in there, then you feel like that's gonna be the end of coal. They straight out said it," said Ryan Hunter, who's worked at the Colstrip plant for 17 years. "What's going to happen when it's all done and over with? There won't be much here."

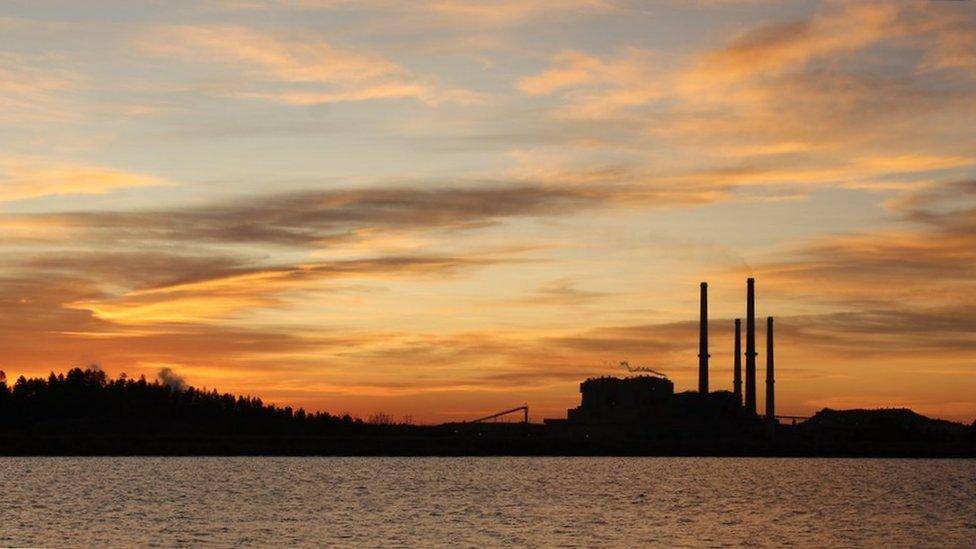

The Colstrip plant is fed by a nearby open-pit strip mine, and together, this so-called "mine to mouth" operation employs about 650 workers at its peak - the very jobs that Trump vowed to save during his 2016 campaign. A month before election day this year, Department of Energy secretary Dan Brouillette came to town and remarked that plants like Colstrip were being retired too quickly, calling it a "very important facility to us", external. That was encouraging to hear in a city where coal energy is pretty much the sole economic driver, making up as much as 80% of its tax revenue.

It's not hard to understand why the residents want to hang on. Because of coal, this tiny city boasts a $12m annual budget, which translates into excellent schools, immaculate city parks and gleaming recreation facilities. The fire and police departments are fully staffed, crime and property taxes are low - there's even a nine-hole public golf course situated under wide open skies, amid red-striped rock formations and the rolling, arid steppe. The average salary is roughly double the statewide average.

"If you were walking down the side of the street and you fell down on the sidewalk, the next car over is gonna stop, pick you up and try to figure out what's going on, and help you out," said Small. "That's how these people are. They're salt of the earth... That's what we're trying to save."

Saving coal and electing Republicans is nearly synonymous here. If you drove up and down the tidy streets of Colstrip earlier that day - a town of less than 2,300 residents with one gas station and one grocery store - "TRUMP 2020" and "Montana for Trump" flags were fluttering over a few front stoops. But far more prevalent were signs that read, "Colstrip United", the name of a pro-coal group of residents founded to push back on environmentalist rhetoric about the town. Many businesses in town hang signs that say things like, "Coal Keeps Us Cooking," and "Coal Keeps the Doors Open".

Locals were incensed by Obama's 2015 Clean Power Plan and its mandate that the state of Montana cut its carbon emissions by 47% by 2030. The plant's closure would have been an inevitability to meet that goal. When a newly inaugurated President Trump withdrew the country from the Paris climate accord and set about dismantling Obama's Environmental Protection Agency policies, workers were thrilled. They eagerly awaited further changes that could potentially save the town.

But salvation for coal never arrived. More megawatts of coal power were retired during the Trump administration, external than the last four years of the Obama presidency, and in 2019, the US mined only 706m tonnes of coal, the lowest level since the 1970s. That same year, two of the companies who own a share of the energy output from Colstrip announced that they were shuttering their portion of the plant, known as Units 1 and 2. Although closure has been talked about for years, when it actually happened the town was stunned. "It's like losing a family member," one woman told a reporter at the time, external.

Those closures led Hunter to move his family to Arizona, where he's originally from. Although he still has a job in Colstrip and travels there to work, he no longer plans to raise his family there. He worries the local high school won't even exist four years from now, when his oldest son would be graduating.

"It's been trickling away here for 10 years, watching this town get a little bit smaller, get a little bit smaller," he said.

At the same time, he still owns a house and a small business in Colstrip that he's been trying to sell for months. There haven't been any takers.

"Say President Trump wins re-election. Yeah, he could possibly try to put a stall on this for a while," said Hunter. "But the end is still inevitable."

John Williams has been the mayor of Colstrip almost continuously since its incorporation in 1998

Colstrip Mayor John Williams spent election day doing chores around the house, trimming his trees, and only intermittently tuning into coverage of the 2020 race. As Biden crept closer to victory, he felt none of the optimism he had experienced four years ago, when the surprise election of Trump held the promise of a friendlier EPA and the unwinding of what Williams saw as unnecessary regulations that were hurting the bottom line of the power companies that own the Colstrip plant.

"Everything in our community is energy related. And if Biden gets in there, I see there's a lot of challenges," he said. "I feel the threat is greater on the federal level."

Indeed, President-elect Biden said he plans to weave aggressive climate change policies into many facets of his administration, from his Department of Justice to the Department of Agriculture. He has pledged to re-join the Paris Agreement on his first day in office and will appoint former Secretary of State John Kerry to a newly created, cabinet-level position as a special envoy for climate. Biden also campaigned on a pledge to achieve zero-emission power in the US by 2035, a timeline that could directly impact the Colstrip plant.

Williams - a former plant administrator who helped incorporate the city in 1998 and has served as its mayor for the majority of the years since - warned that sun-setting coal plants too quickly will lead to brownouts and rate hikes for the people whose homes are currently powered by Colstrip. He said that his residents will not be the only ones suffering the loss of coal tax dollars, the entire state will feel that pain.

However, when he started talking about who is to blame, he sounded just as angry at the companies who own the plant as with any politician or environmental group.

"I feel that those large, multibillion [dollar] companies that have made millions and millions of dollars as a result of the efforts of the people that live and work in Colstrip place little value on what their futures are," he said. "They understand the debt that they owe to this community. They understand it, whether they'll recognise it with actions, I doubt."

Some of the anger in town stems from the abrupt closure of Units 1 and 2. The Colstrip plant's four "units" are jointly owned by six different companies, all of which pay for a percentage of the power generated. Four are out-of-state companies, meaning the majority of the power generated in Colstrip goes to Washington and Oregon states, which have considerably more liberal governments than Montana.

In 2016, Oregon passed a law that would eliminate the use of coal-fired power by 2030. In 2019, the governor of Washington signed a law that would sunset the state's reliance on coal power even faster, by 2025. And under a settlement with the environmental group Sierra Club over violations of the Clean Air Act, two of the plant's owners - Talen Energy and Puget Sound Energy - agreed they would close half of the plant's units by 2022. They shocked the city when they moved up the closure to 2020, saying the units were no longer "economically viable".

Puget Sound Energy pledged $10m to help transition the town, saying in a statement to BBC that it will "remain in Colstrip for years through the decommissioning and remediation work", but workers felt they were caught flat-footed.

"There's no transparency with these companies," said Hunter. "They're just like, 'Oh, we're done.' And it just leaves everybody hanging, nobody gets a chance to try and plan for anything."

The other out-of-state owners could withdraw from Colstrip as early as 2025, leaving two Montana-based companies who - while they have expressed interest in keeping the plant open for years to come - have not said publicly how they plan to do so.

In a statement to the BBC, Montana-based Talen Energy said it is focusing on "keeping Colstrip Units 3 and 4 economically viable amid the changing policy landscape.

"We continue to be guided by doing what is right for our employees and the community."

State senator Duane Ankney has been a fierce defender of coal, and the town, for years

At the time of the closure, state senator Duane Ankney told a local reporter that he'd once believed that Obama's Clean Power Plan would be the demise of Colstrip. But now it is a game of economics, not politics.

"It's the investors and the utilities that have the most say in this," he said. "The policies handed down from Washington or from the state legislature can make it easier to get a mine permit or to get a power plant permit. But they have no swing over what the financials is."

Michael Gerrard, an environmental law professor at Columbia Law School, said there are things a Biden administration could do to continue to make coal an unattractive investment for power companies, like resume the Obama-era moratorium on coal mining on federal land, and strengthen regulations on the waste products and emissions that those facilities produce. He also said that any plan to build rail lines that would bring coal from a place like Colstrip to the coast in order to be sold to foreign markets like China would probably never get past a Biden administration. But none of those things change the fact that coal power is no longer as competitively priced per megawatt as natural gas from fracking, and increasingly viable renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

"The coal industry has been on the decline for several decades," said Gerrard. "Even had [Trump] been re-elected, it's not clear what he could have done to much prolong the lifetime of these plants."

Bret Bowen, the former president of the power plant's electrical union and an employee for the last 20 years, was one of a few Biden supporters in town. Sitting on the front porch of his home, wind chimes ringing in a steady autumn breeze, he said he thinks the town has been used by politicians and the coal industry as a prop - a pawn in a culture war it couldn't possibly win.

He points to the fact that the Trump Department of Energy official who visited Colstrip just before the election mentioned carbon sequestration - a process for capturing carbon dioxide from burning coal and storing it instead of releasing it into the atmosphere - which could prolong the plant's lifespan. But just a month later, a study performed by that same official's department said that in Colstrip, such a plan "may not be financially attractive", external and gave it an estimated $1.3bn price tag.

"If I told you everything was gonna be okay, it's a lot easier to hear that, then, 'Oh, man, I just lost $100,000 in my home value that I can never recoup.' I'd rather you tell me it's okay. And I'll bump down the road every Monday morning because it's okay," Bowen said with a wheezy laugh. "That's easy. That's an easier pill to swallow. Unfortunately, that doesn't make forward progress."

Bret Bowen tends to some of his horses just outside of Colstrip

He said he voted Democrat because he believes it will strengthen union power in the country - for the job he'll need to find after Colstrip shuts down.

The man whose entire job is to figure out what forward progress for Colstrip looks like is Jim Atchison, executive director of the Southeastern Montana Development Corporation. Atchison manages to sound both breathlessly excited about the prospects for Colstrip's economy and frustrated by the sustained fight to make it into a reality.

"The gist of this is we have one horse in the barn right now. And we'd like two or three additional horses in the barn to diversify our economy," he said. "I was here till midnight last night, getting some reports done, but that's kind of what we have to do... it's just people need help."

He can rattle off half a dozen visions of Colstrip's future - perhaps it could become a destination retirement community, or a hotbed of wind power, with its valuable transmission lines that run all the way to the Pacific Northwest. There is already a wind farm under development in the area, which could create enough energy for 300,000 homes. Maybe rare earth minerals could be harvested from the burned coal, or perhaps Colstrip could be a place to develop those elusive carbon capture technologies.

But there is still no single project that is likely to absorb every employee from the coal industry, nor fully supplant the tax base Colstrip currently enjoys. He said the prolonged state of uncertainty has led to a lot of "trauma" in the community.

"There's this big question mark that hangs over everyone's families and their lives out here," Atchison said. "We try and stay positive, we try and look at opportunities - 'How can we turn this lemon into lemonade?' type of thing."

Rancher and Northern Plains Resource Council chair Jeanie Alderson

Some of the proposed job solutions are coming from entities that have historically been at odds with the coal industry, and then by extension the workers in Colstrip. For decades, local ranchers have opposed the expansion of the coal mines and rail lines that would cut across their land, and potentially impact groundwater and soil quality.

Jeanie Alderson, a fourth generation rancher in the area and chair of the Northern Plains Resource Council, said that her group's interests align with workers now that the plant is likely to close. The NPRC released a study showing that if coal companies do a thorough clean-up of the 6.7 million cubic yards of toxic coal ash currently sitting in ponds on the plant property, the project could yield 218 jobs.

"Let's do this clean up, and let's do it right, let's keep people working. And let's take care of the water so we don't all end up with a Superfund site that all of us who are here for the long haul are left with," she said.

The more robust clean-up plan has just been approved by the outgoing Democratic governor's administration. However, it could face potential challenges with the incoming Republican governor, and a new Republican supermajority that Montanans just voted into office.

By the end of election week, it was clear that Biden was likely to win the presidency, and that Jason Small had won his election as well. There was no victory party. When he got off work at the plant, all he wanted was to go home to his small cattle ranch on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, where he was expecting a large delivery of hay. He hadn't had a day off, he said, in four months.

Small said he sees himself as a representative of the "blue collar, working class Natives", like the 200 members of local tribes who work at the plant or the mine. He said the dollars those jobs bring to the reservation go much farther than they do even in Colstrip.

"One job affects seven people. Well, if there's 200 people working from the reservation just south of here, working here in Colstrip, that job affects 1,400 people due to disparities in the system," he said.

Although experts say it's unlikely, Small's nightmare scenario is that a single Biden executive order could have the knock-on effect of shuttering the plant overnight. He has visions of plant managers stopping everyone at the gate one morning - game over. At the same time, he said his last four years in the legislature have made him a realist about what can be achieved on a purely political level when it comes to coal.

"When I was just first doing coal advocacy years ago, I was thinking, 'Oh, we can get on this, we can save this, we can save this.' And, you know, unfortunately, most of the world is below the surface of what you ever see," he said. "At the end of the day, these are a business. And when those businesses don't make money anymore, they shut them down."

As of now, he believes his role is to prolong the life of the plant in any way he can - a subsidy here, a tax break there - to keep the utility companies happy and eke out a little more time for his colleagues to find other jobs, to sell their homes and make a plan for what comes next.

"I still haven't taken the steps myself," he said. "And I do know what's coming. I mean, I fully understand."

At the same time, life for Small has already dramatically changed because of Covid. The virus ripped through the Northern Cheyenne reservation, infecting nearly half the population and causing 33 deaths. In Lame Deer, the largest town on the reservation, electronic signs warn residents to be home by a 10pm curfew. Small lost several members of his own circle to the virus, including his grandfather, his 48-year-old cousin, and a close childhood friend who was only 45. At the tail end of his election, Small contracted the virus himself.

"I've lost so much of my family here lately that you know, I'm kind of hitting that point where, shit, I don't need to stick around. Nobody left," he said with a joyless laugh.

"Every time you lose something, there's less of something to come home to. I don't know, maybe in the end, I'll go on a journey of some sorts and never look back. You never know."