How unsigned bands make money online

- Published

Adverts placed on YouTube videos can turn a profit for their creators.

It's no secret that the last decade has been tough for the music industry. Hit by piracy, recession and falling sales, record labels have shed artists and staff in an effort to stay afloat.

Costs have been cut in almost every area, with one glaring exception.

"What people tend to forget is there is a fixed cost in breaking artists," said Mark Robinson, vice-president of Warner Music last year.

"On average, it still costs $1million (£621,000) to promote and launch a new band."

It's a big figure - incorporating the price of recording an album, styling a band, marketing their music and everything else that finally, hopefully, pushes an act into the mainstream.

But is there an alternative?

A growing number of musicians are establishing their careers on YouTube, with little or no financial outlay. Last year, an unsigned band from New York even entered the Billboard charts courtesy of their online fanbase.

The Gregory Brothers first came to attention with their "auto-tune the news" series, where political debates and press conferences were transformed into miniature operas, thanks to pitch-shifting computer software.

The Gregory Brothers insert themselves into news footage to duet with political leaders

Early videos saw Hilary Clinton singing about Somalian pirates, while the US Congress debated climate change as a call-and-response gospel song.

"Singing is happening all the time when we're talking, but our brains are just too feeble to parse it as music," explains Michael Gregory. "I can change that in the studio."

The clips, equal parts technical experiment and political satire, became a word-of-mouth success, much to the band's surprise.

"After playing a number of shows with 10 audience members we dreamed that, by putting videos online, we could capture double that," says Michael.

"We knew at least that our mums and their six friends would watch, so we could garner at least 12 views," adds vocalist Sarah Fullen Gregory.

The group (actually three brothers and one sister-in-law) regularly gain more than four million views every time they upload a video. Each viewer earns them money, thanks to YouTube's partner programme, and fans have started buying their songs on iTunes.

The chart breakthrough came last summer, after they composed a song based on a disturbing news report from Alabama. A local resident had been assaulted by an intruder in her bedroom. Interviewed for a news report, her brother, Antoine Dodson, launched into a florid tirade against her attacker.

His warning: "hide your kids, hide your wives" became the hook for a propulsive R&B track, which sold more than 100,000 copies, peaking at number 89 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Antoine Dodson's rant became a chart hit. Profits were shared with his family.

"It still feels really strange," says Evan Gregory.

"This week, I was opening a business bank account and I was trying to explain what our small business is. And the banker was like, 'Oh, so you guys make videos kind of like that Antoine Dodson video?' and I replied, 'That is in fact one of the videos that we made.'"

"It's not much of a living, but we have one," adds Michael. "Everything we do is independent and all of our songs originate on YouTube, so it's kind of a new model that we're making up as we go along."

Advertising revenue

But they're not alone. Over in the UK, a duo called Brett Domino have carved out a similar reputation on YouTube.

Based in Leeds, they play cover versions of chart hits on stylophones, drum pads, ukuleles and iPhone apps. Their songs are delivered in broad northern accents with a studious deadpan - sort of like a less charismatic Pet Shop Boys - and they've won a legion of followers.

"We did a Justin Timberlake medley played entirely on handheld instruments, and Justin Timberlake picked up on it," says Brett. "He was a big fan of that video - and our profile's just continued to build and build."

Ste, the silent partner of the group, still holds down a job at a local theatre, but that's partly because the duo refuse to exploit their audience.

"We're making a bit off advertising on YouTube," says Brett, "but the big money is made off pre-roll advertising, which means you have to sit through a three-minute advert before you watch our video, and we think that's not really fair.

"So on a few of the videos, there's little text adverts on the side, which can be annoying, but it does generate a bit of cash. We're also making money off merchandise. We have a range of t-shirts. We're thinking of getting some mugs."

Multiple sources of income are they key to surviving online, as LA indie band Pomplamoose discovered in 2008.

"I was sitting on my computer, trying to figure out how to make a better living in the music industry," says multi-instrumentalist Jack Conte.

"I noticed I had about three plays on MySpace and I went over to YouTube and I saw somebody do a cover song and they had about 600,000 views. I thought to myself, 'man, I'm in the wrong place!'"

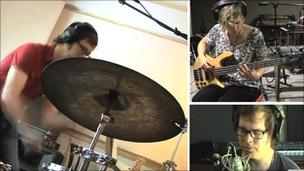

Switching to YouTube, he specifically exploited the site's visual capacity, filming the recording process and using split-screen edits to show every instrument being played simultaneously. Conte also realised the power of cover versions, picking a few timely examples to capture an audience.

"The first one that went viral was Single Ladies by Beyonce," he recalls. "It coincided perfectly with a couple of other viral videos that were going around at the time, all with that song.

"The magic pool of events just swirled around in the right direction and led to a lot of exposure for us."

Pomplamoose's "video songs" illustrate every stage of the recording process

As their reputation has grown, Pomplamoose have introduced fans to their original material - catchy, acoustic, jazz-pop. Because they operate outside the traditional music industry, they retain all the master tapes, royalties and rights in their own music.

Celebrity fans include Ben Folds, who joined the band to record a song on his latest album. Over Christmas, they were invited to soundtrack a series of car adverts.

"One of the revenue streams, a big one, is cover versions," says Jack. "That turns people on to our original tunes, which provides another revenue stream. And then another source of income is licensing - letting a TV show use one of our songs.

"But I'm not sure that we would only be able to do one of those things. It's only the combination that leads to a reasonable, yearly income."

Confusion

So what does the regular music industry make of this?

"I don't believe record companies know what we do," says Jack.

"A lot of them say they do, and yet they still use language like, 'Hey, let's make a viral video.'

"That's a silly thing to say. It's like saying, 'let's make a smash hit movie.' You can make a movie and it either wins an Academy award or it doesn't. It's not something you can seek out."

Evan Gregory agrees: "There's definitely been interest in our group from record labels, but they mostly came to us out of confusion.

"They saw a song on the Billboard charts that they had nothing to do with and they said, 'How did you guys do this without any help from us? Can you tell us how to do it so we can push you out of the business?'

Ben Folds enlisted Pomplamoose to record a bonus track for his last album

"But in the end, we haven't really found a model that will work for us on a major label. That's not saying it can't be done, we just haven't done it yet. So we will continue to be independent for now."

Brett Domino suggests the YouTube model is too capricious for a major label to pursue it.

"We certainly never had a business model - and if we'd set out and tried to do it, we probably wouldn't have succeeded," he says.

"But I'd certainly encourage people to make videos on YouTube and make their own songs, and upload them and promote them the way we have done. I just wouldn't expect immediate success."

On the contrary, says Pomplamoose vocalist Nataly Dawn. "We've recommended this to a lot of our friends, and a several of them are making a living out of it now.

"People think YouTube is a place for kittens and puppies and babies and boobs - but it's really an untapped community and a marketplace.

"It's hard to communicate to people who are attached to the old model of the music industry, but our model works for musicians who want to create their own music and keep that music for themselves."

- Published5 January 2011