Can philanthropy bail out the arts?

- Published

Many arts organisations across the UK are feeling the squeeze as their public subsidies are cut. Can millionaire benefactors step in to fill the gap?

Arts Council England, which has had its budget cut by 30%, will soon tell theatres, galleries and other organisations the bad news - and it will mostly be bad - about their new grants.

The government hopes philanthropists will help fill the gap. In 2009/10, individuals donated more than £350m to the arts in the UK. But 88% of that went to the top 4% of organisations.

So how easy will it be for arts bodies big and small across the UK to tap into private donations? Three arts figures give an insight into the world of philanthropy.

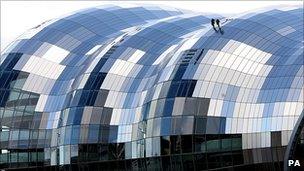

The major venue - The Sage, Gateshead

The Sage Gateshead has successfully persuaded the local business community to donate

Opened in 2004 in a shiny Norman Foster shell on the banks of the River Tyne, the Sage concert hall is named after a local software company and has numerous rooms named by benefactors.

For example, the Katharine Shears studio, a space for workshops and rehearsals, was named by a local businessman in memory of his mother. The Greggs Children's Room, which hosts activities for under-fives, is named after the Newcastle-based bakery chain.

Selling naming rights has raised a total of £12m for the Sage's endowment fund. The interest on that money is used to run the venue, concert programme and community projects. It is philanthropy in action.

It is an example many other regional arts venues would love to follow, especially as 93% of that money came from the north-east.

"There are some people based in London who have given to the Sage Gateshead and continue to do so, but it's not as easy for them to see on a day-to-day basis where their money goes and what we do with it," explains Lucy Bird, director of marketing and development.

The key to persuading people to open their chequebooks is finding out what motivates them, she says.

Some companies support such venues to make the region a better place to live and therefore make it easier to attract and retain staff, she says. Some people want to raise their profile and be connected with a prestigious building. Others want to support specific projects working with children, for example, or a certain style of music.

"Then once you've got them, love them to death," she says. "Keep them involved, keep them close to you, and they will then tell their friends and peers and hopefully the ball will start rolling."

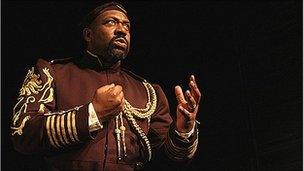

The theatre company - Northern Broadsides

Lenny Henry appeared in a Northern Broadsides production of Othello in 2009

Based in a small office in a former carpet factory in Halifax, the Northern Broadsides touring theatre company has been taking acclaimed versions of classic plays on the road for almost 20 years.

Its first production was staged in a yacht repair shed in Hull. Now, it visits cattle markets and mills as well as theatres. And there is no Norman Foster building for patrons to put their names to. That means it is not so attractive to donors.

"Some of our projects ain't comfortable," says artistic director and actor Barrie Rutter. "There's no velvet seat to invite them to. We don't have a building. You can't come to us like you can go to the opera or the major houses.

"I've been called a maverick so many times that it's virtually my middle name and sometimes that does not attract sponsorship."

The company has had "very handsome" sponsorship from the Halifax Building Society in the past, but that has "dried up and died", Rutter says.

"The philanthropy side of it for us is a non-starter. You can see where it's very easy for bigger organisations, who are building based, or who are more appropriative artforms like ballet and orchestras and opera and are based in the middle of London. It's much easier. And there's an office to do it."

As things stand, philanthropy could not fill a funding gap for them, Rutter says. "We've tried to attract philanthropy based on the fact that we're 20 years old next year and are going to have a year of celebrations. There's not a penny. But it's not for want of trying."

And he resents the government for making cuts, saying the arts generate £6 for the country's economy for every £1 spent on grants.

"The philanthropy side as an objective of this present government is despicable, trying to Blu-Tack it onto British art in the way that they've done," he says.

The philanthropist - Lord Aldington

Lord Aldington says arts bodies need to find benefactors who share their aims and ambitions

Lord Aldington has donated to the Royal Academy of Arts in London - a "very modest" amount, he insists.

He also chairs the gallery's investment committee, is a trustee of the Institute for Philanthropy and is a senior advisor to Deutsche Bank.

Individual philanthropists donate for a number of reasons, he explains. The key is finding a "shared aspiration" - where an arts organisation manages to match a donor's own aims in life.

"That's where the gold lode is," he says. "If you can get people to enthuse about something that you're doing, if you can ring that bell, if you like, that is where you'll get support. And then you will discover that actually there's a lot more money available than you thought there was."

There are other factors. Fashion is another key. "People will give in order to be seen to give to things which are fashionable, in order to get bragging rights," he says. And the most fashionable and prestigious institutions are in London.

"People who want to share in something will of course want to share in the best. It feeds on itself so the capital tends to attract the best."

But many big donors have personal links outside London, Lord Aldington believes, citing a wealthy family with a business in London but whose philanthropy is devoted to the Lake District.

"It's tempting to say the real problem is people in the provinces and they should give up. That's not true." The things that motivate philanthropists are as valid in the north of Scotland as they are in London, he adds.

One other vital factor is the tax arrangements, Lord Aldington says, which are more beneficial than many donors realise.

"In this country the tax deductibility arrangements are very generous," he says. "The thing that is wrong is that nobody knows they're generous because the government has steadfastly failed to sell the message about how good the current system is."

- Published27 January 2011

- Published8 December 2010

- Published28 October 2010