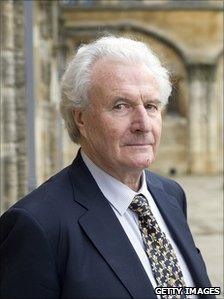

Obituary: Colin Davis

- Published

His performances divided both audiences and critics

By the time he died Sir Colin Davis was the grand old man of British classical music.

At different times he was music director or chief conductor at three of Britain's leading music institutions: the London Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

And in the 1960s he had been an orchestral prodigy.

But his career got off to a shaky start, and his stint at Covent Garden was marked by a series of productions which provoked boos and harsh reviews, as well as plaudits.

Colin Davis was born in 1927 at Weybridge in Surrey, the fifth of seven children. His father was a bank clerk and the family were not well off.

They did not own a piano, but his father had a gramophone and a collection of classical music records to which the young Davis would listen avidly.

At 11, thanks to the generosity of a relative, he was sent to Christ's Hospital school, where he learned to play the clarinet, and it was there, after hearing a recording of a Beethoven symphony, that he decided he wanted to become a conductor.

"It was a revelation," he later recalled. "I had never heard so much energy concentrated into half an hour. I wanted to be a musician and I wanted to be a conductor. It was the most irrational decision that I have ever made."

He won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music, but because he couldn't play the piano he was not allowed to join the conducting class. Instead he trained as a clarinettist and spent 10 years as a clarinet player (part of that time in the band of the Household Cavalry) and as a struggling freelance conductor.

Abrasive

In 1957 he was appointed to his first full-time job, as assistant conductor of the BBC Scottish Orchestra (now the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra).

Colin Davis got his big break in 1959 when Otto Klemperer fell ill and he took his place at the Royal Festival Hall to conduct a concert performance of Mozart's Don Giovanni, with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Joan Sutherland. The critics were impressed.

"I was a raw young man"

The following year he made his debut at Glyndebourne when another veteran conductor, Sir Thomas Beecham, also fell ill.

He first performed with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1959 in a programme that included a tuba concerto by Vaughan Williams which he never subsequently conducted.

But he wasn't popular with all musicians, acquiring a reputation for tantrums and abrasiveness. In later life he put his behaviour down to arrogance and inexperience.

"I was a raw young man," he said in 2007, of his first encounters with the LSO, "and they were a pretty ferocious bunch of pirates. There were no women in the orchestra, except for a harpist who smoked a pipe. And we had lots of battles." Musical standards were high, but not as high as today and players often arrived at concerts drunk, he claimed.

Personal crisis

"The friction was that I was a young man and they were older, and I didn't know much about their profession. And I think they were rather resentful. If you're overly enthusiastic about music, or if you were then, they were very cynical about it, and I don't think I handled it very well. But I survived."

In 1961 he became music director at Sadlers Wells Opera (later to become English National Opera) and in 1967 he was made chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Professional success had gone hand in hand with a personal crisis in the early 1960s. His first marriage, to the soprano April Cantelo, which had produced two children, collapsed when he fell in love with the family's Iranian au pair, Ashraf Naini, known as Shamsi.

The couple had to marry three times to satisfy both British and Iranian authorities, once in Teheran and twice in the UK, and had five children. Lady Davis died in 2010. Sir Colin's second marriage appeared to mellow him.

Davis (l) with the composer Michael Tippett in 1964

In 1970 he succeeded Sir Georg Solti as music director at Covent Garden. He stayed for 15 years though his performances divided audiences and critics; many were booed. He won acclaim with performances of operas by Mozart, Berlioz and Tippett - including the premiere of Tippett's The Knot Garden - and championed the work of 20th century composers including Stravinsky, Berg and Britten.

But his Wagner Ring cycle, in a highly controversial production by Gotz Friedrich, drew mixed reviews. And many critics disliked his performances of operas by Puccini and Verdi. Even so, in 1977 he became the first British conductor to appear at Wagner's own opera house, Bayreuth, conducting Tannhauser.

He didn't much care for many of the modern opera productions he was asked to conduct. On occasion, he told one interviewer, there were "the most awful scenes" when he objected to a director's approach. But often it was difficult for conductors to object:

"You're going to work with someone, you've seen a design, which can be quite different when it occupies the stage. By then you're committed; you can't just clear off and leave the others to get on with it by themselves. It's not professional. You've got a responsibility towards the orchestra and singers, and you've got to go down with the ship."

Grandeur and passion

After leaving Covent Garden he turned down offers from leading US orchestras and went instead to Germany where he spent 10 years at the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra before returning to become the LSO's principal conductor. He was made a CBE in 1965, was knighted in 1980 and became a Companion of Honour in 2001.

In the opera house, on the concert platform and on record he was especially admired for his performances of Mozart, Sibelius, Tippett, Elgar and Britten.

Meeting the Queen in 2009

He championed the music of Berlioz, but confessed to finding Prokofiev and Rachmaninov unsympathetic. A typical Colin Davis performance was full of grandeur and passion, but sometimes a little ponderous.

Nor did he have much time for the early music movement, with its attempts to recreate what composers would originally have heard, with period instruments and small ensembles.

"If you try to tell me that Bach's B Minor Mass sounds good with a chorus of single voices, I don't believe it," he once said. "We're interested in the sound composers heard in their minds, and not what they actually heard."

In later life he was quietly-spoken, seemed to lack self-confidence away from the conductor's podium and claimed to dislike "all that charisma stuff", exuding instead a certain inner calm.

In a BBC interview in 2007 he reflected: "You can find in music something you can't find in anything else, because it makes time meaningful - at least it does to me. Every time you give a concert, time is suspended: you're mastering it; time is not the enemy. It doesn't put off death, unfortunately, but it gives you a very good time while you're still alive."

- Published15 April 2013