Can writing stop prisoners reoffending?

- Published

- comments

As part of its service, the Writers in Prison Network helps offenders to record stories for their children

An organisation that sends writers into prison to work with offenders is among arts groups across England that fear their funding is about to be cut. But can arts for prisoners save the government money?

Erwin James, a former inmate who served 20 years for two "appallingly serious" murders, says prisons are "full of people who are not very good at communicating effectively or appropriately".

"They can communicate with a pool ball in a sock or a razor on the end of a toothbrush or by shouting and bawling," he adds.

The 53-year-old says he went into prison in 1984 "with massive social inhibitions, I couldn't speak or to talk people, I was always acting, I was always trying to be somebody else - I didn't know who the hell I was".

"What we did in the group went back to the wing with us and made us more thoughtful and more reflective," he says. "Writing does that."

Communication is no longer a problem for James, now a successful author and Guardian journalist.

The Writers in Prison Network (WIPN) - started in 1992 by Arts Council England and the Home Office under a Tory government - was "instrumental in making me think that maybe I could do this as a job", he says.

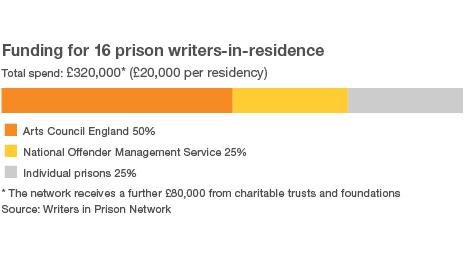

The network funds writers-in-residence, each costing £20,000, at 16 prisons across England. Alongside creative and autobiographical writing, they help offenders with projects including oral storytelling, staging plays, publishing magazines, making videos, producing radio shows and recording rap music.

On Wednesday, Arts Council England - which has had its budget slashed by 30% and which currently funds half of the residencies - will tell the Writers in Prison Network if it is going to reduce or cut its grants.

If it does, the network could be forced to reduce its number of residencies - or even fold.

Erwin James, who now lives with his wife in the Welsh borders, is one of a handful of offenders helped by the network who have gone on to make a living from writing.

Its real ability to transform lives comes in building up the "very, very low self-esteem" of prisoners, says poet Pat Winslow, the writer-in-residence at category A prison Long Lartin, in Worcestershire.

"I think it's really about opening doors, oddly, in prisons," she says.

"People who are in prison have often been victims themselves and they've often had very little opportunity to express themselves or even find themselves. So I think writing is a way of validating life experiences and, also, finding out who you are and articulating things."

For some, like 53-year-old Esther Maurice, who says she was convicted of accidental injury thanks to "a rather perverse jury decision", it was "something to fill the hours" while she served three months of a nine-month sentence at Styal prison, in Cheshire.

"It was very difficult to bear under the circumstances - I really needed something to do with my time so I didn't stew about it," adds the mother-of-three who is now writing a book based on her experiences of prison life.

But for another ex-prisoner, who did not wish to be named, the poetry he wrote in Shrewsbury prison while working with its writer-in-residence had a more profound impact.

"It definitely stopped me from reoffending," says the 41-year-old from Barnstaple, north Devon.

"Before, I didn't know how to express my emotions, it used to come out in bad ways but now I'm a hell of a lot calmer," he adds.

"It usually used to come out in violence, it did boil over inside and get worse and worse and then it would explode."

Now, instead, he says he "actually feels the anger flowing through my pen and on to the paper".

Despite applying for 300 jobs without success since his release last year, he says he has a new-found confidence and is setting up his own business selling greeting cards featuring his own poetry.

No illusions

The latest figures released by the Ministry of Justice suggest that, in 2009, 59% of prisoners who served sentences of less than 12 months were reconvicted within a year. The figure for young offenders was 72%.

While little research has been done to measure the impact of the arts in prison, Writers in Prison Network co-director Clive Hopwood is confident its work "helps contribute towards people not reoffending, or reoffending to a lesser degree".

"The average cost of keeping someone in prison is £47,000 so if one of my writers - at the price of £20,000 - can have influence on one person to stay out of prison for one year, £27,000 is saved by the taxpayer," he says.

"Lots of people will say, 'prisoners are enjoying putting on plays and making videos - why should they have all the fun when they've committed crime'?"

"But there are 85,000 people in prison and all but a handful are coming out on a street near you soon. Would you like them to be better or worse?"

Lifer-turned-journalist Erwin James is also under no illusions about public sympathy for prisoners.

"Some people think my situation's great - 'oh wow, you're rehabilitated,' they say. Other people think rehabilitation is an insult to the victim.

"It's a difficult one - what do you do? I did the best I could."

James, who also completed an arts degree with the Open University while he was inside, agrees rehabilitation is "not just for the offenders' sake, it's for all our sake".

A National Audit Office report published last year found that reoffending by criminals serving short prison terms in England and Wales cost the taxpayer up to £10bn a year.

"Anything that reduces the chances of that happening - arts intervention, education, giving people a chance once they get out - that's going to save us all a whole lot of money," he says.

"The arts is a real means of allowing you to feel some self-respect and self-worth. People that feel like that are less likely to want to cause other people harm."

The government and Arts Council England declined to comment ahead of Wednesday's grant announcements.