Will L.A. Noire change the game for actors?

- Published

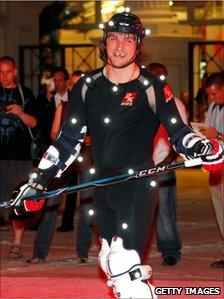

Mike McGrady (inset) and his character captured by MotionScan technology which uses HD cameras filming 360 degree views of the actor's face

Hailed as a breakthrough in the gaming genre, L.A. Noire was released last week to rave reviews from critics, with particular praise for the game's photo-realistic characters.

Players control the character of LAPD detective Cole Phelps as he attempts to solve a series of brutal murders in sprawling 1940s Los Angeles.

The title, from game publishers Rockstar, has since topped the UK gaming charts.

All 400 actors were filmed delivering their lines in two-hour sessions

More than 400 actors were cast and using a new technology called MotionScan, every inch of the performer's face was mapped and rendered into a 3D model.

It is the latest step forward from the type of motion capture technology which is still used in the game to render the characters' bodies and was used in films like Lord of the Rings and Avatar.

With five years development, an estimated budget of around $50m (£30m) - the equivalent of a modestly-priced movie - and a relatively untested new technology, there is a lot riding on the game's success.

Providing voiceovers for video games has long been a sideline for jobbing actors, an extra revenue stream in an industry of ever greater competition for roles.

But will these new techniques attract bigger names and directors into performing in games, or is there still some snobbery about "acting" in a video game?

Legitimate acting

US actor and star of US cop show Southland, Mike McGrady plays a police detective Finbarr 'Rusty' Galloway in the game and insists "this technology and video games are here to stay".

"This is not something that was just a flight of fancy and this was the end of it," he adds. "These things are legitimate and there's big money in it.

"It is performing and I think most actors just love to perform well-written characters and well-written storylines. It's not like doing voiceover work, this is you performing in front of a camera so I do think that more actors are going to jump on board."

The 32 cameras used in MotionScan shoot 1,000 frames per second

Geoff Colman is head of acting at the Central School of Speech & Drama in London and he agrees that actors can't afford to be too choosy when it comes to the medium they work in.

"The question of whether technology diminishes an actor's performance was much discussed and lamented in ancient Greece with the introduction of stage machinery in their theatres, so, in that sense it's nothing new.

"It's about how the actor collaborates with the technologies of his or her day. I think we would be very static and very churlish to pretend that this isn't happening and therefore, we need to be there with this and meet it."

McGrady admits that, as far as the performances go, the actors were forced to "heighten the animation of our faces so that the cameras could read it".

But he insists "that's where a good director can help find that fine line between hamming it up and making it real and believable without making it overly dramatic".

Too real?

Reviews of the game's MotionScan have used phrases like, "more convincing facial animation than we have ever seen in a game", external but also sometimes unnerving , externaland "creepy real".

The "creepiness" of the characters plays into the "uncanny valley" theory that explains why almost-human looking robots scare people more than mechanical-looking robots.

The phrase, which was coined back in the 1970s but whose foundations lie even further back, holds that when a simulated human looks and acts almost, but not quite the same as an actual human, it causes a feeling of revulsion in people.

The actors' bodies are still animated using motion capture technology

Yet, a sequel to the game is already being hinted at.

Brendan McNamara, the founder of the Australian studio behind L.A. Noire told BBC Newsbeat that "over the next couple of years you'll see it (MotionScan) become full body so they can do the whole thing in costume and what that means is you'll be filming in 3D".

Geoff Colman says he expects more actors to treat working in gaming the same way as they would working in any other medium.

"The territory in which an actor now exists is not exclusive, it's not located in some sort of old-fashioned binary between film and theatre, it is all-embracing and it would be a very retrograde and stagnant artist who would reside in the past.

"We have to look to the future and what is the artist's function but to communicate? And if the high-tech new-ness of this form is the next part of our journey of communication, we have to be there with it."