Obituary: Seamus Heaney

- Published

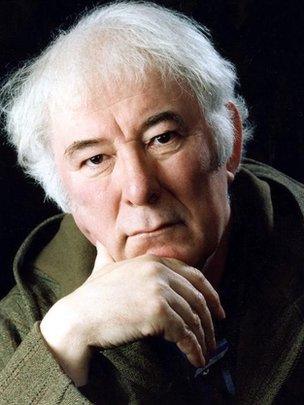

Heaney's poetry was always accessible and approachable

Seamus Heaney was internationally recognised as the greatest Irish poet since WB Yeats. Like Yeats, he won the Nobel Prize for literature and, like Yeats, his reputation and influence spread far beyond literary circles.

Born in Northern Ireland, he was a Catholic and nationalist who chose to live in the South. "Be advised, my passport's green / No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast the Queen," he once wrote.

He came under pressure to take sides during the 25 years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and faced criticism for his perceived ambivalence to republican violence, but he never allowed himself to be co-opted as a spokesman for violent extremism.

His writing addressed the conflict, however, often seeking to put it in a wider historical context. The poet also penned elegies to friends and acquaintances who died in the violence.

Describing his reticence to become a "spokesman" for the Troubles, Heaney once said he had "an early warning system telling me to get back inside my own head".

Born on 13 April, 1939, on a family farm in the rural heart of County Londonderry, he never forgot the world he came from. "I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells / Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss," he recalled in Personal Helicon.

He was a translator, broadcaster and prose writer of distinction, but his poetry was his most remarkable achievement, for its range, its consistent quality and its impact on readers: Love poems, epic poems, poems about memory and the past, poems about conflict and civil strife, poems about the natural world, poems addressed to friends, poems that found significance in the everyday or delighted in the possibilities of the English language.

Seamus Heaney: Poetry was entrancing

The very first poem in his first major collection was called Digging, and it described his father digging potatoes and his grandfather digging turf. It ended:

But I've no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I'll dig with it.

His roots lay deep in the Irish countryside

It proved to be his manifesto. He spent a lifetime digging with his pen, but returned often in his poetry to the landscape and society of his boyhood in a countryside of farms and small towns, where Protestant and Catholic rubbed along tolerably, if warily, and one of his earliest memories was listening to the shipping forecast on the BBC.

He was a bright boy: At the age of 12 he was sent on a scholarship to St Columb's College in Derry and studied for a degree in English at Queen's University in Belfast.

He became a schoolteacher, then a lecturer, at Queen's and later head of English at Carysfort College, a teacher training college near Dublin.

For more than 20 years from 1985 he spent part of each year at Harvard as a visiting professor and later Boylston professor of rhetoric and oratory, and then as poet in residence. From 1989 to 1994 he was professor of poetry at Oxford.

Childhood memories

But in 1972 he gave up full-time academic work to become a freelance writer and poet. His first collection, Death Of A Naturalist, had been published six years earlier in 1966.

Much of it was about his boyhood.

The title poem described the revulsion of a child fascinated by frogspawn when confronted by adult mating frogs; there were poems about his father ploughing, about his mother making butter and about the death in a road accident of his youngest brother, for whose funeral Seamus was summoned back on a "Mid-Term Break" (the poem's title) from school.

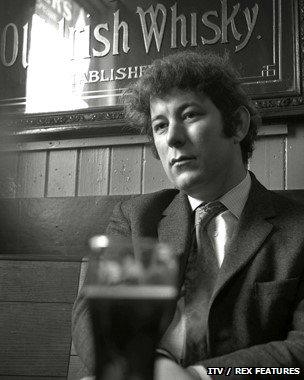

He studied then lectured at Queen's University, Belfast

Childhood memories featured in much of his subsequent verse. A Sofa In The Forties, published in Spirit Level in 1996 (when Heaney was 57) describes the young Seamus and his siblings turning the family sofa into a railway train, under the wireless shelf:

Out in front, on the big upholstered arm,

Somebody craned to the side, driver or

Fireman, wiping his dry brow with the air

Of one who had run the gauntlet. We were

The last thing on his mind, it seemed; we sensed

A tunnel coming up where we'd pour through

Like unlit carriages through fields at night,

Our only job to sit, eyes straight ahead,

And be transported and make engine noise.

A decade later, many of the poems in District and Circle harked back to the "land of lost content", which was the County Derry of his childhood.

He wrote often, too, about the landscape of the north of Ireland, especially the turf bogs. He was fascinated by iron age corpses preserved in peat, and by the job of cutting turf: Arduous, routine but satisfying.

Baking bread

Then in North, published in 1975, a new, darker tone entered his work. Six years earlier, violence had erupted in Northern Ireland. It was the start of a quarter century of bombings and shootings, riots and brutality, internment and hunger strikes, murder and misery.

He addressed The Troubles in his writing

There are poems in North about peat bogs and about Heaney's memories of his aunt baking bread. But there is violence too and political commitment, which made the collection controversial when it first appeared.

Poems like Funeral Rites, Whatever You Say Say Nothing and the sequence entitled Singing School are explicitly about the Troubles and the divided, unequal society that produced them. The violence depressed him; in Funeral Rights he wrote:

Now as news come in

of each neighbourly murder

we pine for ceremony,

customary rhythms:

the temperate footsteps

of a cortege, winding past

each blinded home.

Act Of Union was Heaney's take on the relationship between Britain and Ireland

In 1975's Act Of Union, he took the map of Britain and Ireland and turned it into an image of a married couple lying in bed together, Ireland surrounded and mastered by the masculine Britain.

The Act Of Union, he said once before reading the poem, was both a political and a sexual concept.

"To put it metaphorically, and yet historically, Ireland, the feminine country, was entered by England, possessed by England, planted with English seed, withdrawn from by England, and left pregnant with an independent life called Ulster, kicking within her."

He sometimes despaired of his fellow-citizens in the North. In an ITV documentary made at about this time he said: "We're a society, if you like, that's fallen from grace. This is limbo land at best, and at worst the country of the damned."

'Veneers are important'

But he was always alive to the complexities and ambiguities of the Irish situation, and suspicious of the vigour with which sectarian positions were adopted.

"Forthrightness is great, but it shades into triumphalism at times, it shades into obstinacy and it shades into vindictiveness," he said in a BBC interview in 2006.

"So you're caught between a language of diplomacy which opens a path, which is a very, very narrow path, it's just a chink of some sort... you're caught between that diplomacy language and the yearning for forthrightness, living with the ambiguity of asking yourself, 'Am I being insincere, or am I being courteous?' People live on a very fine edge there in the North."

Heaney's poetry sought to shine a light on the underlying reality of life in Northern Ireland - but also to celebrate those who kept going with daily life, who maintained a veneer of civilisation. "Veneers are very important. Without veneers how do we conduct civil life? Veneers are important between enemies and friends. I don't think it demeans something to say it's a veneer."

Heaney was a broadcaster and raconteur alongside his teaching and writing

Despite his own republican views, he attended in 2011 a dinner at Dublin Castle along with the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh, hosted by Irish President Mary McAleese and her husband.

This January, he waded into the row over a decision to restrict the flying of the union flag above Belfast City Hall. The ruling triggered weeks of violence, but Heaney said loyalists should be allowed to fly the flag.

There was "never going to be a united Ireland," he said, so "why don't you let them (loyalists) fly the flag?"

'Everyday miracles'

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s Heaney's reputation grew steadily. It helped that he was prepared to talk readily about his work, unlike many poets; and that he was a genial fellow capable of self-mockery and at ease in public.

He was known irreverently in some quarters as "famous Seamus".

His work became more "public" too: He joined the board of an Irish theatre company, Field Day, founded by the dramatist Brian Friel and the actor Stephen Rea, and in 1990 the company produced The Cure at Troy, Heaney's translation of Sophocles' tragedy Philoctetes.

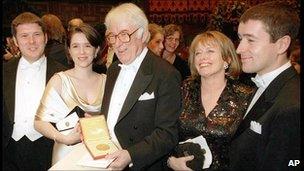

His international reputation was sealed when in 1995 he was awarded the Nobel Prize, "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past", in the words of the Nobel citation.

He continued writing, and further honours followed. In 1996 he won the Whitbread Prize for his translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. In 2009, he was awarded the £40,000 David Cohen Prize by Arts Council England for a lifetime's achievement.

District and Circle, published in 2006, won the TS Eliot Prize for poetry. The critics were struck by the title poem, about a journey on the London Underground in the wake of the 7 July bombings, which also evoked the medieval Italian poet Dante's vision of hell in his Inferno.

It was characteristic of Heaney who, as well as being a farmer's boy, was also exceedingly bookish and erudite.

His Nobel citation referred to "works of lyrical beauty"

By the end, Heaney had acquired a reputation not only for cleverness but for wisdom, a poet who took seriously his role (he called it "a vocation") and was prepared to engage with the real world in work that was accessible and approachable.

And he had readers in high places. Nine days before the announcement that he had won the Nobel Prize, President Bill Clinton, no less, at a state banquet in Dublin Castle quoted the closing lines from The Cure At Troy, as Northern Ireland crept tentatively towards peace:

Now it's high watermark

And floodtide in the heart

And time to go...

What's left to say?

Suspect too much sweet talk

But never close your mind.

It was a fortunate wind

That blew me here. I leave

Half-ready to believe

That a crippled trust might walk

And the half-true rhyme is love.

- Published30 August 2013

- Published18 November 2011

- Published21 December 2011

- Published6 October 2010

- Published30 January 2013