Banned Ken Loach charity film gets rare airing

- Published

Until now Loach's film has only been viewed by a few BFI archivists

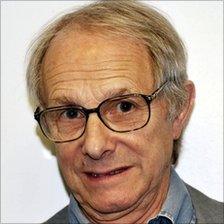

A 1969 documentary by Ken Loach, made for and later banned by Save the Children, has been shown to an audience of critics and colleagues in London.

The untitled film will have its public premiere on 1 September and forms part of a major retrospective of the British director's work at BFI Southbank.

The film took a critical view of the charity's work in the UK and Kenya that its backers felt subverted its aims.

"There was a showing and not much was said," the 75-year-old Loach remembers.

"People left the room, and then we heard from the lawyers."

The 53-minute film was co-funded by Save the Children, then celebrating its 50th anniversary, and London Weekend Television.

"We assumed LWT would support the independence of a critical eye," said Loach on Monday. "But they just backed away."

As a result, the piece was consigned to the British Film Institute's National Archive "and the key thrown away".

With Save the Children's blessing, however, the documentary will finally be screened - more than four decades on from when it was made.

So what was it about the film that displeased the charity? Ironically, it was partly the opinions of its own employees that Loach recorded.

Travelling to a Save the Children home in Essex, the director filmed its employees making disparaging remarks about the parents of the young Mancunians in their charge.

Later in the documentary, Loach travels to another institution in Nairobi where children were forbidden to converse in their native tongues.

Instead they were inculcated in the ways of Kenya's former colonial overlords - open-air parades, Tom Brown's Schooldays and lots of PG Wodehouse.

"It is a bit embarrassing to see that," said Justin Forsyth, chief executive of Save the Children.

"But I think it's good to air these issues and we should be big enough to take it on the chin.

"Save the Children has changed a lot, but the issues that come out in the film about colonialism, aid and charity are still relevant today," he continued.

"I think it's great it's being shown. I don't think we should be in the film censorship business and we shouldn't stifle debate."

'Staggered'

"We went [to Kenya] with an open mind to see what the work was," said Loach. "When we got there, we were absolutely staggered.

"It was clear to us the function of the school was to provide a middle class to run the civil service and create the veneer of independence."

The director's socialist principles are reflected in a quotation by Marxist theorist Friedrich Engels that opens the film.

Loach says it is "surprising" this month's urban riots did not happen before

Elsewhere, black political activists are seen bemoaning the way foreign businesses took money out of Kenya and how aid money is used.

"In our mind it was always about how charity affected the context in the countries in which they were operating," says Loach, whose other films include Riff Raff, My Name is Joe and Looking for Eric.

"Looking at it now it's a very lumpy film, but I defend the essence of it."

Fans of the director's dramatic work will recognise the indignation with which he views the poverty and deprivation of 1960s Manchester.

It is the same social inequality, he says, that fuelled the recent outbreaks of urban unrest in London, Birmingham and other UK cities.

"I think if you've got a million young people unemployed that will have an impact," he told the BBC News website.

"There's an alienated, disaffected population of mainly young people who have no stake in society and seemingly no future.

"Traditionally when young people were growing up, they were introduced into the adult world through work. They don't have that now.

"I think it's surprising it hasn't happened before."

- Published20 July 2011