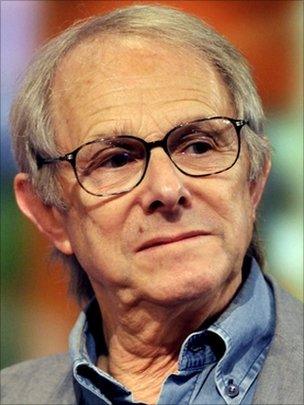

Ken Loach: Uncomfortable truths

- Published

- comments

"Oh dear," said Ken Loach as he entered the room. "What's wrong with natural light". I looked at the very talented BBC cameraman who had spent the last half an-hour meticulously lighting the room for my interview with the esteemed director. "It flattens the picture" the cameraman explained, before helpfully adding "video isn't like film".

"I see," Ken said graciously. And then winced as he sat down and a 300-watt bright, white light locked onto his eyes. That had to go. Which was a shame because it was the star of our lighting show - without it everything was rather drab. A re-think was required. While we re-set Mr Loach gently tapped his watch and mentioned something about his new movie having to come out next year.

Shortly after the fourth watch-tap the cameraman sighed, scratched his head and reluctantly switched off his lights. He then rolled-up the blinds and watched as Ken Loach sat motionless in his chair - now warmed and lit by some late summer sun - without a trace of smug amusement in his eyes.

Loach's determination to prevail is so discreetly embedded in his gentle countenance, that it is quite easy not to realise that you have acquiesced. And when you do, not to mind. His conversational tone, humility and openness are beguiling. To most.

But back in 1969 - the year that his Bafta-winning film Kes opened - he really annoyed the Save the Children Fund, by making a documentary about the charity that was far from charitable. A situation that was made a lot worse by the fact that Save the Children had helped pay for the film. But then Ken Loach is not the sort of chap who will compromise his beliefs for a few quid.

He told me that it was not his original intention to make a film criticising Save the Children, but after researching the organisation he felt compelled to report what he saw. The documentary depicts the charity mostly in poor light and as an old-fashioned, bigoted, snobbish, cruel and manipulative organisation.

It opens with scenes of rundown terraces on the outskirts of Manchester while a narrator tells us that the children who live in the houses are taken-away from time-to-time by Save the Children for a jolly good scrub.

We see and hear from the austere Auntie Lena and disciplinarian Uncle Chris; then employees of Save the Children and into whose care, kids as young as nine were put for a number of weeks. Tales of cold baths, beatings and indoctrination ensues.

We then take off to Nairobi and to a special school run by Save the Children. It is a surreal set-up where vulnerable Kenyan children are plucked from the street and selected for the charity's very traditionally British educational institution where their native tongue is banned and they are taught to read and appreciate PG Wodehouse. It is a bizarre passage.

Maybe naively, given Save the Children helped fund the production, Loach didn't think they'd be a problem with getting his documentary shown. His confidence was predicated on the knowledge that London Weekend Television (now part of ITV) had paid the lion's share (two-thirds) of the budget and had commissioned the film. He felt certain LWT would back him up and screen the programme. He was wrong.

According to Loach an agreement was eventually reached where LWT / Save the Children would not sue him as long as the film was never shown.

Apparently the preference of the joint-funders was to destroy the film but they had consented at the last moment to the BFI (British Film Institute) keeping a copy as long they "threw away the key". The filmed was duly retained by the BFI, as was the key.

So now, 42 years later the documentary will be shown in public for the first time at the BFI, external in London on 1 September. The film's presentation is part of a Ken Loach 75th Birthday retrospective at BFI Southbank, although if you didn't know his age he'd easily pass for a 55-year-old. Political engagement would appear to be healthy for those involved as well as for democracy.

The reason that the film can now be shown is due to Save the Children giving the BFI permission to do so. It is a shrewd and appropriate change of mind. It gives the charity a chance to distance itself from its past and providing an opportunity to talk about itself as a contemporary institution.

The film jumps between England and Kenya

It will also offer social historians a valuable insight into post-war Britain. For film buffs it's a chance to see a piece of previously unknown work by one of the greats of realist filmmaking. And for fans of documentary making it is fascinating.

The first half of the film is mostly taken up with images showing life in Save the Children establishments, over which a series of unseen people express their opinions about how the institution is running its affairs.

It is not until half way through that we see our first talking head, which by modern standards is radical verging on revolutionary. Nowadays TV execs don't like more than 30 seconds to go by without seeing someone speak.

The effect of not doing so is to heighten the power of the spoken word - like radio with pictures. It is even more effective when the spoken word contradicts the pictures. There's a passage where a Kenyan boy is dressed-up in the full British public school kit and doing something jolly decent while a voice tells us that "they are really much happier in mud huts".

The political line is set from the top with a quote from Friedrich Engels opening the programme. The polemic of the piece is clear: socialism is best. Ken Loach grins and nods when I remark on this. It is the polite smile of a person who has just be told the bleedin' obvious by someone who knows less than they do. Of course it's socialist his eyes are saying, what did you expect?

As we leave Ken asks the cameraman if he is a member of BECTU. "No" is the reply. "I'll pop downstairs and fetch you a form then" said the irrepressible director.

Save the Children might have changed; Ken Loach hasn't.