Is there a novel that defines the 9/11 decade?

- Published

- comments

Many books have been written about 9/11 but is there one that embodies the era that the attacks inaugurated?

When Changez, the Pakistani hero of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, watches the Twin Towers come crumbling down, he smiles.

Little Oskar Schell, the nine-year-old at the centre of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, grapples with his father's death by creating a flip-book - 15 blurry stills, arranged in reverse order, of a man falling to his death from the World Trade Center. When he flicks through the pages, the flailing figure is restored to the top of the building - safe.

In Open City, writer Teju Cole describes Colonel Tassin - a (real) 19th Century figure - who kept count of the number of birds killed by flying into the Statue of Liberty, as many as 1,400 a night. The image is a reminder of another killing by collision, also in New York, two centuries later.

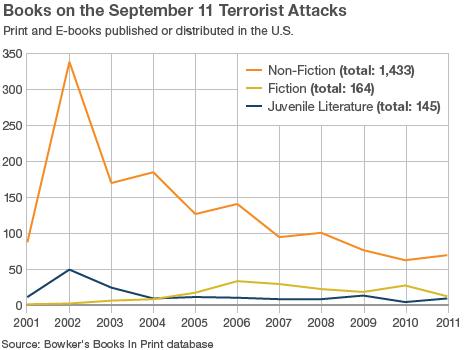

These are three books that have attempted to hew fiction from the fact of 9/11. According to Bowker's Books in Print database, which tracks print and e-books published and distributed in the United States, 164 such works have been written so far - they either directly address the event or use it as a peg to hang greater literary concerns about love, life and loss.

According to Erica Wagner, Literary Editor of The Times, such epoch-making events have traditionally proven to be great canvasses for the imagination.

"Everyone wonders: what if it had been me? What would I have done? It is the job of the novelist to think that through," she says.

Tragedy has often led to an outpouring of art. The Spanish Civil War spawned Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls; the bombing of Dresden, gave rise to Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughter-House Five. The single bloodiest day in the history of human warfare, the Battle of Borodino in 1812, features in Tolstoy's magnum opus War and Peace.

The 9/11 attacks shook the world and the way we think about it. It makes sense for novelists to feature it in their works. But in the 10 years since, has there been one novel that has seized the imagination more than any other - and that stands out as the story of our times?

Ping-pong

The search, it seems, is still on. It is tempting, at the turn of the decade, to hand out such accolades - but as an impetus for the imagination, says Wagner, such events don't come with a sell-by date.

"Ten years is not a long time from the standpoint of fiction," she says.

"If you look at Dickens's novels, for instance, they appear to be contemporary to his times. But often he was writing about his childhood - that in itself is a distance of about 40 or so years."

War and Peace appeared more than 50 years after Napoleon invaded Russia. Michael Shaara's The Killer Angels, a fictional representation of the Battle of Gettysburg, took 120 years to arrive. By contrast, Joseph Heller's Catch-22 was written in 1961 - just 15 years after the end of World War II.

According to John Sutherland, Professor of Modern English Literature at University College London, there is a "hand-in-glove" relationship between fiction and current events but "it is not like ping-pong - fiction doesn't necessarily provide a direct response".

Nostradamus

It is possible, he says, that the novel which comes to define the 9/11 era may have nothing to do with the event itself - at least in terms of plot.

"When the towers first collapsed, a book that shot to the top of the bestseller list was The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold [narrated from heaven by a murdered child] - signifying, perhaps, a general fascination with trauma."

Nostradamus, he says, regained popularity for similar reasons - as people began thinking about the end of the world.

Teju Cole, author of Open City, says his 9/11 novel is Elizabeth Costello by J M Coetzee - although it has nothing to do with 9/11 at all.

"It takes up the question of whether there are limits to what can be depicted of human suffering. In the US, we heard a lot about 9/11 but saw very little of it - little of the actual human damage of that day and little of the human damage that came out of the 9/11 wars," he says.

"Who decides what others may see? Even photographs of soldiers' flag-draped caskets were banned."

According to Mohsin Hamid, author of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, the very attempt to find definitive novels - works that define or specify precisely - is misguided.

"Events should have as many definitions as the number of people who experience them," he says.

When Japanese forces blitzed Pearl Harbour on the morning of 7 December 1941, this was not merely an event that forced the United States to officially enter World War II, he argues.

"Pearl Harbour was many other things also: it was a kiss, it was a swim in a lake, it was a fisherman wondering what the commotion was, it was a flock of birds taking flight."

It is natural for 9/11 to reverberate in fiction, he says.

But if what we want are answers and straitjacket definitions - "history in a hurry" - then are we looking in the right place?

"Fiction is a long, rambling encounter with many things," he says. "Fiction re-complicates what politicians wish to oversimplify."