Claire Tomalin: Dissecting Dickens

- Published

Award-winning biographer Claire Tomalin tackles Charles Dickens in her latest book. After chronicling the lives of Samuel Pepys, Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy, her biggest challenge this time around was deciding which events to leave out of the Victorian novelist's tangled life.

Claire Tomalin: "I rather owed it to Dickens to take a wider look at him"

"Writing Charles Dickens' biography is like writing five biographies," says Claire Tomalin.

Much loved for his novels, which turned a critical eye on Victorian England, Dickens was also a prodigious journalist, court reporter, traveller, editor, theatrical impresario, walker, philanthropist and philanderer.

"He had intense energy," Tomalin says. "Always doing five things at once."

"He called himself 'the inimitable', which was only slightly a joke - because he knew he could do more than most people."

His energy must have been infectious - Tomalin's biography zips through Dickens' 58 years at the same breakneck pace he lived them, barely pausing for breath as he graduates from sketch writer to celebrated novelist, courted by royalty at home and abroad.

Not that it skimps on detail. Whether writing Oliver Twist or setting up a home for the redemption of prostitutes, Dickens leaps from the page with a rare vitality.

The prologue finds the author serving on a jury at the inquest of a dead baby, born to a servant girl. Not only does he persuade his fellow jurors to clear the girl of murder, he finds her a lawyer and sends her food in prison.

Tomalin describes Dickens as a "creative engine"

His charitable acts are widely celebrated, of course, but Tomalin doesn't flinch from depicting his darker side - the bully whose eyes flash like "danger lamps" and whose daughter calls him "a wicked man".

This is a character who, having gone cold on his marriage, erected a partition in the bedroom so he could sleep apart from his wife.

Tomalin admits it was a hard task to compress Dickens' eventful life into 400 pages.

"I showed the first draft to my husband [author Michael Frayn] and he said I spent too much of the book going, 'and then, and then, and then'.

"I said if it's not 'and then' it's got to be 'meanwhile!'

"With Dickens it's always meanwhile. He's writing a novel, meanwhile he's setting up a theatre enterprise, meanwhile his wife is pregnant again, meanwhile he's quarrelling with his publisher, meanwhile he's planning to go off to Italy.

"There's this running multiplicity of facts. Weaving them into a coherent narrative is very difficult. It's like constructing an elaborate building."

Controversy

Tomalin was born Claire Delavenay in 1933. Her parents separated when she was seven, and she found solace in poetry and books, one of which was Dickens' Great Expectations.

Reading it was, she says, an "overwhelming experience". One which stayed with her throughout her education at Cambridge, raising five children, the death of her first husband (journalist Nicholas Tomalin, who was killed while reporting on the Yom Kippur war in Israel) and latterly her career as a writer.

Dickens, pictured with his daughters Mary and Katey, at his home in Kent

Aged 69, she won the Whitbread Award for The Unequalled Self, her biography of Samuel Pepys - but she had always had Dickens in the back of her mind.

The author had what Tomalin calls "a walk-on part" in 1990's The Invisible Woman, the story of Ellen Ternan, a young actress who became Dickens' lover and companion in his later years.

It is thought the couple, with an age difference of 27 years, had a son who died in infancy.

In her new book, Tomalin even speculates that Dickens could have breathed his last at Ternan's residence, his body moved later to avoid a scandal.

The Invisible Woman is being turned into a film, directed by Ralph Fiennes ("We're having great fun," Tomalin says) but many Dickens aficionados have refused to read it.

"I was a bit surprised," says Tomalin. "Some people took deep, profound objection to my even having written the book.

"Somehow one isn't supposed to lay a finger on the sacred reputation of our great writer."

Even now, when Tomalin gives a talk about Dickens, someone ("always a man") will stand at the back of the room "with a notepad at the ready" looking for flaws or inconsistencies in her argument.

But her association with Dickens has had its upsides, too.

"After The Invisible Woman, a man sent me quite a few of Nelly's letters," she says. "An amazingly kind thing to do."

Those letters allowed her to flesh out the story of Dickens' relationship with Ternan in her current biography.

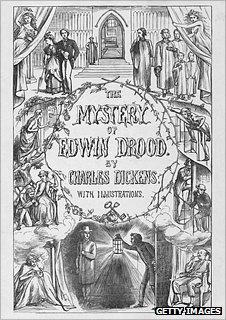

Dickens' final, unfinished novel is being adapted for television

"People said, 'Oh, it's just gossip.' But the more I look at it, the less it is just gossip - because there's more and more evidence."

Yet, despite a wealth of sources - Dickens' published letters run to 12 volumes alone - the smallest details can sometimes prove elusive.

One passage in the biography lists more than a dozen different, sourced descriptions of Dickens' eye colour.

"If you look at any biography, you always find this," laughs Tomalin. "It's obviously quite impossible to fix on an eye colour, but it's particularly striking with Dickens. It goes the whole way from blue to black.

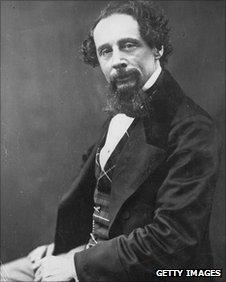

"But he was obviously a strikingly handsome young man. He had this Regency style of bright, dandyish clothes and wonderful curly hair tumbling over his collar.

"He also seems to have been quite vain - there are plenty of accounts of him combing his hair in public."

In conversation as on the page, Tomalin brings her subject to life with an energetic economy.

Does she share his conviction, expressed in The Pickwick Papers, that "it is the fate of all authors to create imaginary friends and lose them in the course of art"?

"I always feel sad when I come to the end of a book," she confesses. "I cried when I wrote the chapter on Pepys dying, even though I knew it was coming.

"There really is a sadness when you part company... Except, you never really do part company. The book doesn't end when you finish writing it. In fact, I now feel I have a large family of very diverse characters who remain in my life very, very strongly.

"I sometimes think that, since I started writing biographies, I've had more of a life in books than I have had in my real life."

Charles Dickens: A Life, by Claire Tomalin, is published on Thursday, 6 October by Viking.

- Published25 January 2011

- Published20 November 2010

- Published13 January 2011