Does cinema film have a future?

- Published

- comments

Darren Aronofsky sat back on his sun-lounger and smiled broadly.

It was early September and the film director was a happy man.

The weather was terrific; he was in Venice, and was thoroughly enjoying his role as chair of the Venice Film Festival jury. "And what," I asked, "did he like best about being chair?"

"Seeing all these great movies projected on 35mm film," he said. "It's so rare nowadays."

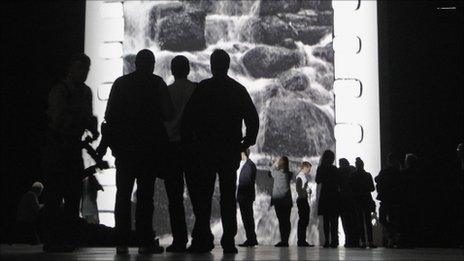

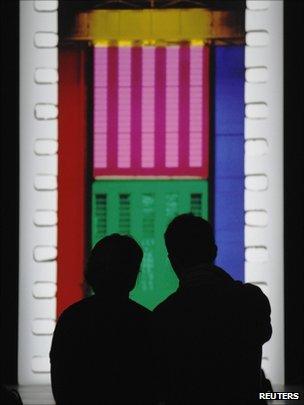

This morning the artist Tacita Dean is sitting at the far end of the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern.

The entire space has been blacked-out for her installation, Film (2011), which has just been unveiled to the press.

It consists of a 14m (42ft) tall monolith upon which her silent 35mm film Film, is being projected.

It is in a vertical, portrait format, which is very unusual. So is the nature of the installation: part artwork, part campaign piece.

The artist is using the opportunity of being asked to fill this very public platform to raise awareness of what she says is the imminent demise of film; as a medium for making and presenting.

And as an artist who uses film to make and show her work, she feels shocked and frustrated. She compares not being able to use film with a painter "being told that paint will no longer be available".

Analogue art

A book has been published to accompany the exhibition, in which she has invited 80 or so interested parties to comment on the crisis.

Among them are Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

Scorsese says that "no matter where cinema goes, we cannot afford to lose sight of its [films] beginnings".

Spielberg is more poetic, saying: "My favourite and preferred step between imagination and image is a strip of photochemistry that can be held, twisted, folded, looked at with a naked eye, or projected onto a surface for others to see.

"It has a scent and it is imperfect... I will remain loyal to this analogue art form until the last lab closes."

Which, according to Tacita Dean, could be sooner rather than later.

Her campaign is not anti-digital, but pro-film.

Her point is that they are very different mediums, with different characteristics, which produce different results.

And even if digital is able to mimic the look and feel of film, it cannot mimic the process of making, which forces the film maker into technical and artistic situations digital does not.

That is the making side of things, but there is also the exhibition side: the screening of a finished film.

Nowadays even if a movie has been shot on film it is often shown digitally (Aronofsky's point), which he and many others say is not the same visual experience.

Tacita Dean goes back to her comparison with paintings.

"If you were a painter, would you want the viewer to see your painting or a digital reproduction of it?" she asks.

Of course there are market forces, and all sorts of other real world issues to consider.

But it would be a great loss if digital became the grey squirrel of the arts.

Music has fought back by making vinyl more available and the public have responded. What will the film industry do?

Update: Here's my report for the News at Ten on the latest installation in the Tate Modern's Turbine Hall.

Tacita Dean: ''I've turned the Turbine Hall into a strip of film''

- Published10 October 2011