Three royal treasures that shed light on the monarchy

- Published

- comments

Visiting dignitaries are typically given guided tours of items from the collection

I admit it; I was a little taken aback when the Queen strolled by. I ought not to have been. After all I was in her house. But still, it was odd: surreal.

Then again, that's Buckingham Palace for you. George IV's opulent makeover of his father's central London residence into a lavish palace fit for a Prince Regent is at once full of magnificent things whilst being brazenly over the top. It is also fascinating, and every object within it tells the story of its royal residents.

While making The Art of Monarchy for BBC Radio 4, I found myself in the White Drawing Room. As State reception rooms go, it is way out there. Think King Midas meets Goldfinger.

Everything is golden: sofas, piano, wallpaper, chairs, mirrors, tables, screens, candelabra and even the fireguard. It is George IV at his most theatrical, mixing shimmering splendour with questionable taste.

In one corner there is a concealed door made to look as if it is part of the wall, in and out of which the royal residents sometimes come and go to their private quarters. More theatre. If the bling-filled room wasn't dazzling enough, I was there to examine Carl Peter Faberge's glittering Mosaic Egg, external, made by the Russian jeweller for Tsar Nicholas II to give to his wife Tsarina Alexandra in 1914.

The egg, which is about the size of a tennis ball (although slightly taller), is made out of platinum and gold and decorated with emeralds, rubies and diamonds.

Each tiny precious stone has been cut with such precision that it fits into a bespoke section of the egg's intricate platinum lattice without recourse to clasps or settings. Inside is a removable piece that features a cameo of the Russian couple's five children. It is an exquisite and poignant object.

Three years after the Tsar gave the Faberge egg to his wife he was in deep, deep trouble. The Bolsheviks had removed him from power and were looking to finish the job by killing him and his family. In this moment of dire need, he turned to his first cousin, King George V, and pleaded to be given exile in Britain. The King refused, worried that by acquiescing to his relative's request he would threaten his own popularity.

Tsar Nicholas and his family

Within months Tsar Nicholas, his wife and their children had been murdered by the Bolsheviks. The revolutionaries took the Tsar's Faberge collection and subsequently sold some of the fine pieces - including the Mosaic Egg, which was brought in 1933 by another monarch as a present for his wife. Quite what Queen Mary thought or felt when George V presented her with this glorious trinket nobody knows.

Along the corridor from the White Drawing Room is the Ballroom. Designed and built during Queen Victoria's reign, it was once the largest room in London. The Ballroom was opened in 1856 with, appropriately enough, a ball: a grand party to celebrate the end of the Crimean War.

It has been in fairly constant use ever since. State banquets, concerts and investitures all happen within its mighty 36m by 18m footprint. During the course of making the programmes I have watched Goldie present a gig in there, and observed members of the royal household preparing a 78ft (23.7m) table for dinner.

I have even been "knighted" on its throne dias - meaning I have knelt on the actual investiture stool and been dabbed on the shoulders by the actual sword that the Queen uses on such occasions. The Queen wasn't on the other end of the sword, but nevertheless…

She uses the same Scots Guards dress sword, external that her father George VI employed for investitures. He chose it because he was the regiment's colonel and was no doubt proud when he removed the sword from its scabbard to reveal a blade embossed with the regiment's battle honours.

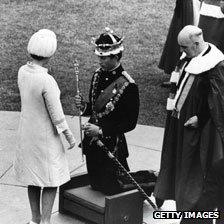

The Queen using the investiture sword

The sword acts as a reminder of the very special relationship that exists between the monarchy and the country's armed forces. Commanding the loyalty and respect of the armed forces has long been a crucial aspect in the art of monarchy. "We don't swear allegiance to this or that government, but to the monarch who is the personification of the nation," Sir General Mike Jackson, the British Army's now retired Chief of the General Staff, tells me.

The one time when the monarchy failed to keep the armed forces on side resulted in the Civil War and their ejection. The royals got back in track in 1660 with Charles II, but monarchal life was never quite the same. Money, Charles found, was in short supply. Which was embarrassing for a monarch looking across the Channel and seeing the shimmering glory of Louis XIV living the life of a Sun King at Versailles.

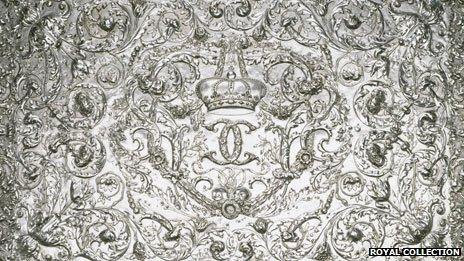

Not to be outdone, the cunning Charles struck a deal so shady he could have ended the monarchy for good. At Windsor Castle you can find a small but spectacular silver side-table, external. The heavily embossed - and therefore totally impractical - object was commissioned by Charles II in about 1670. He believed that a monarch should be surrounded by magnificence in order to command the respect of his subjects and rivals.

Charles II's silver table

But without the money to implement his grand plan he had to do some royal "outside of the box" thinking. He came up with a solution that makes Del Boy's convoluted and risky schemes appear considered and astute. Charles decided to get Louis XIV to pay. Which, in a roundabout way, he duly did.

And, in an ironic reversal of fortunes, while the British monarchy has kept its fabulous silver table, the French have found themselves a bit short. An expensive war with Holland meant that they had to melt down much of their high status silver to fund the war effort.

To come across objects such as these is like finding an old cinema ticket in your pocket - proof, evidence, of what went before. The paintings and artefacts amassed over the centuries by our kings and queens not only shed a fresh light on the monarchy, but also help to bring the past alive.

The heavily embellished table top