Andy Warhol's 'lost' movies uncovered

- Published

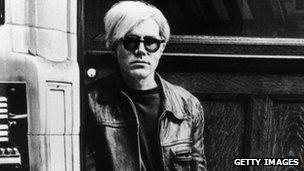

Warhol's experimental films mostly disappeared from view in the early 1970s

Though best known for his paintings, Andy Warhol spent five years producing films. Yet most have barely been seen for decades, as a new book reveals.

At the end of 1963, Andy Warhol took a lease on a former hat factory at 231 East 47th Street in New York City. The studio, which has long since vanished, became known as The Factory.

Some people called it The Silver Factory, because originally almost everything was either covered in silver foil or painted silver - including the toilet.

It was a hang-out for Warhol's friends and for the many hangers-on who hoped his growing celebrity would rub off on them.

But it was also a place of work, turning out the silkscreen images which made Andy Warhol famous around the world. Not only that, but the 37-year-old was experimenting with film-making as well.

US academic Douglas Crimp of Rochester University has just published a study of more than 50 Factory films which have been restored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Roughly the same number are still to be preserved.

"Often people have an idea of what they think a Warhol film will be, even if they haven't seen any," says Crimp. "But there isn't a single type of Warhol film.

"You can say that generally he didn't edit his films. But beyond that, there are big variations.

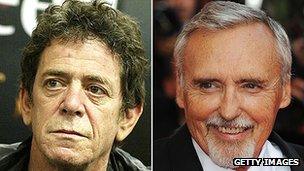

Lou Reed (l) and Dennis Hopper were among those who made 'screen tests' for Warhol

"There are the silent short films, mainly in black and white. But there's also Sleep, which is a very long silent film of [performance artist] John Giorno sleeping.

"Or there's Empire - a static shot of the Empire State Building running eight hours. Later there was a film called **** (Four Stars), which originally lasted 25 hours."

According to Crimp, Warhol's early movies "were made with a Bolex camera, which had a 100-foot reel giving four minutes of screen time. So a 40-minute Warhol film would consist of 10 short reels spliced together.

"Later he borrowed an Auricon camera, initially to make Empire. It took a 33-minute-reel, so that changed what he could do."

In addition there are almost 500 so-called Screen Tests, a single reel of someone who frequented The Factory.

Many of those featured were obscure, but there were also appearances from the likes of Lou Reed and Dennis Hopper.

'Totally nude'

One person who appeared in a handful of the early films was a young actor called Allen Midgette. He recalls a rare shoot that took place outside New York City.

"I phoned The Factory to see what was going on and Andy said: 'Oh, we're all heading down to Philadelphia to make a film, why don't you come along?'

"Somehow he got us into the Museum of Art after hours, but he had no idea what to shoot.

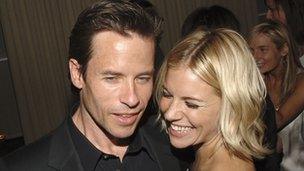

Guy Pearce played Warhol in Factory Girl alongside Sienna Miller's Edie Sedgwick

"They gave me a small loin-cloth; otherwise I was totally nude. In the very centre of the room was this incredible sphinx from Egypt on a platform. So I climbed up there - I was on LSD.

"Andy immediately got it and started shooting. There's something very dynamic about straddling in the nude an Egyptian sphinx."

Midgette also appears in The Nude Restaurant, a Warhol film he says was his idea. "I'd said to Andy why don't you rent a diner and I'll play the waiter?

"Well, I thought probably nothing would happen, but to my surprise he said one day: 'Oh, we found a restaurant.'

"So the next thing is we're all asked to take our clothes off. There were never any parts in the movies - they always asked you to take your clothes off and just sit there."

'Compositional genius'

In later Hollywood films such as I Shot Andy Warhol and Factory Girl - in which Sienna Miller played Warholian 'muse' Edie Sedgwick - The Factory is shown as buzzy. But Midgette says it wasn't like that.

"The Factory wasn't that interesting a place to be," he explains. "When filming was going on you couldn't say Andy was directing it: he wasn't saying a word.

"He hadn't prepared you for it and there were no interruptions: whatever happened happened. It wasn't like this Hollywood feeling.

Todd Haynes (r), pictured with Pearce, is one film-maker for whom Warhol was an influence

"When you walked in, Andy was very likely to point out a picture and say: 'Oh, do you want to do a little painting on that?'

"I always said no because I wasn't even getting paid as an actor, so why should I paint and not get paid also?"

Yet Crimp doesn't accept that Warhol wasn't a director. "Perhaps it was partly true of the early films, which had a static camera set-up: he just let the actors carry on and do whatever they wanted.

"But by the time you get to his later films, many of them have an extremely mobile camera and you can see Warhol's compositional genius. He's a very big figure in the history of gay cinema."

Warhol's 1967 film Chelsea Girls proved a minor hit and for a while it seemed Warhol movies could make money. By this time many of the shots were being called by Warhol's associate, Paul Morrissey.

Crimp says the change was partly because porn films had become easier to distribute in the US. Though the erotic content of most Warhol films is limited, they had an undeserved reputation for being explicit.

In June 1968 Valerie Solanas took a revolver and shot Warhol at The Factory's new location on Union Square. He was lucky to survive.

'Brand Warhol'

After his recovery his interest in film-making waned. Morrissey, though, went on to direct feature-length titles such as Flesh and Heat which were marketed as part of 'Brand Warhol'.

The films mostly disappeared from view in the early '70s. But Douglas Crimp thinks they stayed an influence.

"At the time they were central to the underground experimentation going on. Since Warhol's death [in 1987] they've gradually come back into circulation."

Far from Heaven director Todd Haynes, claims Crimp, has seen at least some of the movies and was influenced by them.

Although more than half the Factory films have now been restored they remain hard to catch. MoMA in New York only rents out 16mm copies, with galleries occasionally permitted digital screenings.

A few titles appeared in Italy but there has been no authorised DVD release. But perhaps it is their near-invisibility which gave Warhol's films their place in the mythology of 1960s America.

Our Kind of Movie: The Films of Andy Warhol by Douglas Crimp is published in the US by The MIT Press.

- Published12 January 2012

- Published30 June 2011