Booking Bob: Bringing Redford to the interview chair

- Published

- comments

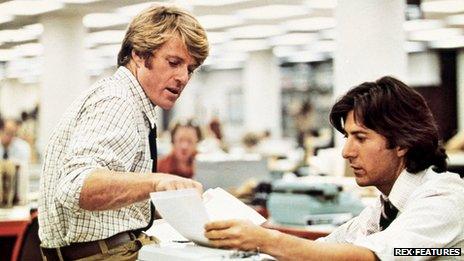

Robert Redford: 'I came in when journalism had reached an apex of morality and professionalism'

"You'll need to hire the room for much longer," I tell my producer.

"Why?" she asks.

"He's always late. Famously so," I answered.

"We have it for three hours - that has to be enough," she says, looking concerned.

"I'm not so sure," I say, blithely knocking back a tasty wheat beer recommended by the attentive waiter at the bar on Spring Street, New York, where we're having our night-before prep talk.

"Oh dear," she exhaled, and finished off her water.

I feel for her. Really. She is one of the BBC's finest news producers: polite and intelligent and determined.

She has produced pieces on war zones and natural disasters, riots and elections, but in one - strange - walk of life she is a total innocent: she has never ever dealt with A-list celebrities.

Booking Bob (as the mission became known) was her job. Redford is coming to London with a three-day version of his Sundance Festival and I wanted to talk to talk to him beforehand to find out why.

A month or so ago his PRs asked if we would be willing to fly out to Utah and meet at his home that doubles up as the location for all things Sundance (film festival, institute, workshops).

"You bet," I replied.

That didn't come off. A week or so later. Would I go to LA? Yes, if I have to. That didn't come off either. And then.

How about New York? Always.

Bob was booked. We had a time (9am), a date (6 March) and a place (the Elizabeth Taylor Suite in the uptown hotel in which Redford was staying).

We arrived early for the interview. We knew we were in for a long wait, but coffee was booked - and, well, it was the Elizabeth Taylor Suite. It was 8:40am.

He was due at 9am. Fat chance. Where the TV trigger?

"He's here."

"What?"

"HE'S HERE."

"He can't be here - it's only 8:45am," I reasoned. "He is ALWAYS late."

Robert Redford says he finds older women who have no surgery attractive

"Well, who's that then?' asks my producer in a kinder and more considerate manner than I deserved.

And, true enough, standing in the doorway looking a little bewildered was Robert Redford.

"Hi," he said. "Where do you want me?'

"On the terrace please," said my producer, "but do you mind waiting so we can film you with Will as you walk out?"

"Oh, I see, some b-roll stuff. Sure no problem," replied the Oscar-winning director.

As he made his way over he had a couple of words with his hovering PRs, which was interesting to observe.

You can often gain an insight into a star by the way his or her handlers respond in their presence.

Some are fearful, others tense; a few are colder than the mountains of Utah in winter. Bob's lot were calm but deferential. He knew them. Asked about their family lives. Teased them a bit.

Pleasantries over, he came out to the terrace. I asked if I could call him Bob, he couldn't see a reason why not.

Dressed in a black open-neck shirt, jeans and deck shoes (without socks) he appeared as relaxed as any 75-year-old man could who was about to be subjected to a 45-minute interview before catching a plane to finish cutting a film on the other side of the country.

He chatted away as we walked towards the bar stools set up for the interview, behind which were the castles of commerce that dominate Manhattan's skyline.

As we sat down he thanked me for "coming over" in a way that was beyond platitudinous, it was a display of good manners that I took to be genuine: Redford is a courteous and considerate man.

As we sat down I noticed he moved like a man feeling - if not looking - his age. I wouldn't go as far to say he appeared frail, but nor did he seem physically powerful.

Below the shoulders he is slight, his legs are thin: his hands purplish with liver spots. Above the shoulders is a different story.

His eyes really are electric blue, his hair golden and his weather worn face just as handsome (and untreated) as it ever was.

His brain, by the way, is working at full wattage, but his voice is not.

On a scale of one to 10 - if 10 is shouting and one is whispering - Bob is operating at one-and-a-half.

I am one metre away from him and I can barely hear a word he says.

When a clanking noise starts on the roof to the right ("drones" he suggests) and is joined by a stiff wind he is completely inaudible.

Talking that quietly is a sign of someone of high status. It is a take-it-or-leave-it challenge: a control thing. It could also be a fatigue thing.

Redford has three concurrent careers - filmmaker, environmental activist, and the figurehead and founder of the Sundance Institute.

He takes a front seat in all cases, sometimes as the driver pushing a project forward, at others in a supporting role, guiding and cajoling.

I had planned to start the interview with questions about why he was bringing a slice of the Sundance Festival to London ("We were asked"), before moving onto his politics and his personality.

Although he did not receive a screen credit, Redford co-wrote the script for All The President's Men

But he was having none of it. Half way through answering my first question about Sundance (he wants to give America's independent filmmakers a chance to put across their view of the US) he veers off into politics.

"My country is obsessed with winning," he says. "As you can see in our current political debates, it's all about winning. And what people will do and say just to win."

He is "angry at" and "embarrassed" by America's political leaders, whom he judges to be "not the best or the brightest".

He says the country has been going downhill "ever since Bush" and that those running for the Presidency are "stuck in the 50s" and "frightened of change".

"Why," I ask, "didn't he go into politics?"

"Are you kiddin' me?" he shoots back. "It's too narrow... you can't be yourself. Have you seen any of those guys being natural, unless they're so crazy they're natural."

The cameraman stops the interview to change his tape. Redford leans over to me and says: "You used to work at the Tate, right?"

"Right," I confirm, a little taken aback. Robert Redford is a busy man - where does the find the time or inclination to check out my potted history?

"I like art," he says slightly sheepishly. He wants to talk about art. No, that's not quite right. He wants a proper conversation about art. He's the one leaning forward now and riffing on Egon Schiele.

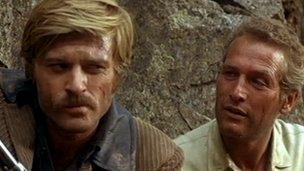

The moustache Redford refused to shave off for the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

In the short time it takes for the cameraman to re-set us we have covered the Post Impressionists, Baudelaire, the time Redford was down and out in Europe and Paris when he was 20 and seriously considering becoming an artist, and a recent exhibition of his art of which he was clearly proud.

When we snap back into interview mode the mood has changed. It's more convivial. And either I've become used to his hushed tones or he's projecting a little more.

He is good natured and thoughtful and quick to a one-liner if the chance arises. He has imposed no time limit on the interview or question areas that are out of bounds. Once committed, he's committed.

Asking well-known people personal questions can feel impertinent, until you realise that they are just like the everyone else, and like nothing more than talking about themselves. Bob is no exception.

He finds older women who have had "no work done" attractive. He accepts he is obstinate and that it has probably been the making of him (he refused to shave off his moustache in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kind and nearly lost the gig).

He says he likes to watch people, to "pay attention" but finds it hard because of his fame. "Does he like being Robert Redford?" I ask.

"There are moments," he says, "like being happy... just moments."

I ask him if he could be remembered for one thing - filmmaking, activism or Sundance - which would it be.

He pauses, and then looks up. "Performing," he says. "It's my core. Everything else came from that."

- Published29 March 2012

- Published7 March 2012

- Published15 March 2011