Psst - heard about the blockbuster show with no queue?

- Published

- comments

If you want an insight into contemporary London life go to the Courtauld Gallery, external on the Strand.

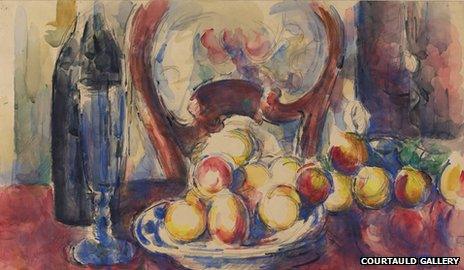

There you can see one of the world's greatest collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, external, including: Van Gogh's Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), Cezanne's Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1887), Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1881-2) and Renoir's La Loge (1874).

You will find that those famous paintings are but the tip of the great art iceberg that is the Courtauld Collection: a classy eyeful in a splendid setting. You will also find that they are likely to be all you have for company.

When I visited Tuesday morning, the galleries housing the permanent collection were practically empty. In my experience they nearly always are.

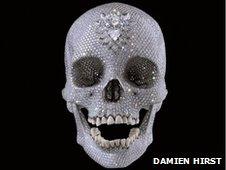

For the Love of God by Damien Hirst

Yet across the river at Tate Modern people are queuing to go into a darkened room and convene with Damien Hirst's diamond skull, external.

Or are standing 10-deep and shoulder-to-shoulder on the fifth floor in white-walled galleries trying to catch a glimpse of the Tate's own collection, external.

Both of which are worth a look, but then so is the Courtauld Collection. In fact I'd argue that a trip to the Tate is all the more enjoyable if preceded by a visit to the Courtauld. It is where you get chapter one of the modern art story, with Tate supplying chapter two onwards.

Apples, bottle and chairback by Paul Cezanne

But unlike a tour of Tate Modern, a visit to the Courtauld isn't considered an event. And it is art events that capture our imagination in 2012. If you were to package the Courtauld Collection as a must-see Impressionist show at the Royal Academy or National Gallery the queue would back-up all the way to Hampstead. And we'd happily pay £14 to see it in cramped conditions as opposed to the £6 the Courtauld charges to peruse it in peace.

Portrait of Helena Fourment by Peter Paul Rubens

So, there you have it. Art's ability to reveal life's universal truths is not limited to the physical works, but extends to how we view them. Which was the reason for my visit to the Courtauld in the first place.

Saskia with one of her children by Rembrandt van Rijn

I'd gone to view a display of drawings from the collection, external to see what they might reveal about the revered painters who produced them. The curators of the display have selected 59 works on paper from the 7,000-plus from which they could choose. Those on show span over 500 years, taking in Leonardo, Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Rubens along the way, before ending with Cezanne, Matisse and Van Gogh.

A painting is like the lead singer in a band: colourful, up front and attention grabbing. It dominates the heart and mind - it is most of what you see. But behind the bright colours and brilliant brush strokes lurks the scaffolding that makes the facade look so good. There you'll discover a drawing that lays bare the artist's technique - it is like reading a musical score or seeing an architect's plans. It is in the drawn line that a composition is created and forms settled upon.

And mistakes made.

Seeing Leonardo's ideas develop through his drawings is tantamount to watching him work. You can almost hear the great man tut, as he erases one line and adds another. This is the directness that a drawing provides and a painting does not: you get private access to the creator's mind and process.

Studies for a Saint Mary Magdalene by Leonardo da Vinci

It is also the stage where the only meddling that occurs is by the artist. The early drawing is known as the vidimus: a draft plan produced by the artist to show his or her client to approve and improve by way of suggestion.

But it is the apparent simplicity of a drawing that intrigues my most. I find studying a quick sketch by a great artist rather like reading the words of a great writer. The lines they draw and the words they write seem wholly within one's own reach, and yet when they are combined in composition something approaching alchemy happens and a work of art appears that is far beyond the rest of us.

Stephanie Buck, the curator of the show, attributed it to control: an ability to see the big picture and the finer detail, and then to portray them coherently. It is what units Leonardo with Cezanne: Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

I have always thought of those parings as distant cousins in the history of art. But having gone around the Courtauld display I now realise I was wrong. They are more like brothers, sharing similar concerns and techniques. It was only when paint was applied that the differences between the renaissance artists and the founders of modernism became seismic.

I'd recommend a visit. Alternatively you could go to the Design Museum, external and see its Christian Louboutin exhibition, external, which has attracted a record number of visitors down to its Shad Thames home.

Great shoes more popular than great art? It's a sign of our times.