London 2012 Festival: Were the arts as inspiring as the athletics?

- Published

Stars of London 2012 Festival: Conductor Gustavo Dudamel and the Big Dance world record attempt

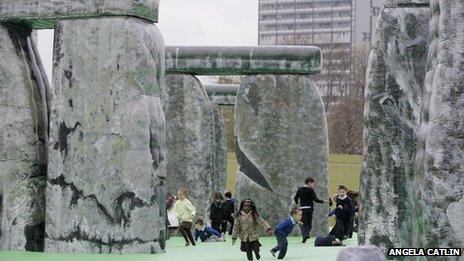

It boasted bell-ringers, a bouncy Stonehenge and a string quartet in helicopters. But how well did the London 2012 Festival engage its audience, and what will be its legacy?

When Coldplay brought the Paralympics to a close on Sunday, it also marked the end of a four-year programme of arts events known as the Cultural Olympiad.

Its climax was the London 2012 Festival, external - 12 weeks of concerts, exhibitions and events across the country that ran alongside the summer of sport in the Olympic Park.

Organisers revealed this week that 19.5 million people had taken part in the London 2012 Festival events by 31 August, with a final week of attendance figures yet to come in.

The general opinion seems to be that, after a shaky start back in 2008, the Cultural Olympiad ended on a high.

"It's been a journey from things that were on a small-scale community level to this festival with nearly 20 million people involved," says Tony Hall, the chief executive of the Royal Opera House, who came on board to run the Cultural Olympiad in 2009.

"That is a very large-scale statement about arts and culture in this country."

The festival had an overall investment of £55 million, including lottery cash and sponsorship from "premier partners" BP and BT. Now organisers are beginning months of number crunching to make sure it was money well spent.

Hadrian's Wall was lit up in an arts project called Connecting Light

"Did they get the biggest bang for their buck? Yes, I think they did," says Philip Spedding, director of Arts and Business, external.

"It was a neat bringing together of a whole range special commissions and other events that were going on already, and marketing them as a single entity.

"That was a smart way of getting a major punch when you don't have an awful lot of money to start with."

While the Olympiad team looks at the feasibility of holding a biennial arts event, Spedding says that the private sector had a central role to play in these cash-strapped times.

Organisers of any future major cultural event, he advises, should start talking to businesses "a lot earlier than they would normally imagine doing so".

Spedding still has the original booklet about the Cultural Olympiad from 2008 and notes how few of the original ideas actually came to fruition. But he praises the efforts of the festival team, led by director Ruth Mackenzie, who took over in 2010.

"What they did do in the end was amazing and they did it incredibly quickly," he says. "But you can't keep doing these things by the seat of your pants. If you want to do it again, you have to get the planning right."

The London 2012 Festival opened on 21 June with five headline events across England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Grabbing most of the headlines was The Big Concert, external in Stirling. Led by superstar conductor Gustavo Dudamel, it featured an orchestra of local school children, many from the Raploch council estate, who had not played an instrument as recently as four years ago.

How is the event viewed 12 weeks on?

"The overall reaction to the Big Concert was positive," says Gregor White, a reporter for the Stirling Observer, external. "It was great to see local kids getting the chance to perform on such a huge stage and receiving such an enthusiastic response."

He added: "Though arguably an important step up for the orchestra, the Big Concert was just the latest in a whole series of steps they've taken over the past four years.

"However there were a few voices raised immediately after the concert about how 'real' a picture it presented of Raploch, and I guess the legacy question is still as open here as it is on the sporting front."

The children's orchestra has now been invited to Venezuela next year on a trip funded by music education programme El Sistema and Sistema Scotland, external, with support from Stirling Council.

In Wales, festival events included Adain Avion, external - a mobile art space inside an aircraft fuselage - and the Power of the Flame, external, which involved young people across the whole of the country.

Inflatable Stonehenge: Jeremy Deller's Sacrilege was part of the Festival

"The main achievement of both of these was the fact that it got people engaged with the arts who might never have got involved before," says Karen Price, external, chief arts correspondent for the Western Mail, external.

She adds that on the theatre front, Coriolan/us from National Theatre Wales, external was staged in a former aircraft hangar and attracted four and five star reviews, while Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru's Welsh-language version of The Tempest, external (Y Storm) merged the circus with Shakespeare.

"Both productions showed that Welsh theatre is now at the forefront, really pushing boundaries and reaching out to new audiences," says Price.

The cultural baton has now been handed to Londonderry, UK City of Culture 2013, external as well as Glasgow, host city of the 2014 Commonwealth Games, and Rio de Janeiro where the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games will take place.

One arts organisation that was directly involved in the London 2012 Festival was the Frieze Foundation, external, which curated and produced six new public art projects in east London.

"A lot of the artistic programming came with the condition that the local community was taken into account," says Sarah McCrory, curator of Frieze Projects.

"The local community aspect is important, but a slight criticism might be that there could have been more funding for art projects for art's sake, as it were. It would have been interesting to have a bit more scope, but it didn't restrict what we did."

Of the festival programme as a whole, McCrory was excited by the amount of activity though there were some projects "that weren't great in terms of quality".

"Obviously it's been really successful in terms of getting people out and about," she says.

"There have been some good programmes to get young people involved, whether it is apprenticeships or visits, the creative sector always needs to encourage more children, particularly from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

London 2012 Festival director Ruth Mackenzie was recruited in 2010

"When you can make a young person aware that there are good jobs in the art world, I think that's a good start."

One such project during the 2012 Festival was the Creative Jobs Programme. Run by the Royal Opera House, external, it gave 40 long-term unemployed young people the opportunity to undertake paid work at some of the organisations involved in the Cultural Olympiad.

While the Olympiad in its early stages came in for criticism for the breadth of its ambition, there are those who see the whole concept as flawed.

Professor Pavel Buchler, of Manchester School of Art, external, says the idea "promotes unhelpful associations of culture with competition".

"Unlike the Olympic Games, the Cultural Olympiad has no history or tradition and no real meaning. It is bad enough that sport, culture and broadband are conflated in the same government department.

"Such ideas as the Cultural Olympiad make matters worse by shoe-horning or black-mailing art into a propaganda role and do nothing for the recognition of art in its own right."

Not that this is likely to worry London 2012 Festival director Ruth Mackenzie as her team analyses the final figures.

"All of our partners want to know what happens next in economic and cultural terms. There's a lot of work to gather all that together," she says.

"The creative industries are one of the huge success stories of the UK - you give us money and look how we market ourselves and the country. Cultural tourism is one of the most important assets we have."

So has the festival, as the sport hoped to do, inspired a generation?

"What we have ensure is that we can offer every young person something to dream about," says Mackenzie.

"For those that can't be world-class athletes maybe the arts and creativity offers another way forward.

"Maybe they want to be Jude Law or Rihanna or Jay-Z or Gustavo Dudamel.

"Certainly every child in Raploch wants to be Gustavo Dudamel when they grow up, and that's thanks to London 2012 Festival in part."

- Published27 August 2012

- Published14 August 2012

- Published6 August 2012

- Published26 April 2012

- Published21 June 2012