Meeting Salman Rushdie

- Published

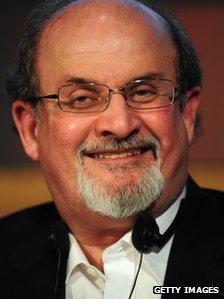

Salman Rushdie: "My view was and is that nothing is off limits"

His route to the interviewee's chair is blocked: a decision has to be made. He can either duck down beneath a five-foot high neon light, or walk under a ladder. Salman Rushdie, shorter and stockier than I had imagined, chooses the latter.

He emerges wearing a slightly perplexed expression, typical of a person about to be subjected to a television interview; a guest of honour awaiting instruction.

Directions are given, hands are shaken and jovial comments are made: an atmosphere established.

The famous author sits: pensive but poised.

"So," I begin, "Salman Rushdie, why this book now?"

"I wasn't ready to write it earlier," he answers. "I felt not emotionally in the right place. Also, I felt I wanted to slam the door on the past and get on with my life."

At 656 pages, Joseph Anton: a memoir by Salman Rushdie is weighty in every sense. It could have been heavier still had the Indian-born, New York domiciled, Booker Prize-winning author not cut it by two hundred pages.

It starts with the moment he takes a call from a BBC journalist asking him how he feels about Ayatollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa calling for him to be put to death. It was the first Rushdie had heard of it.

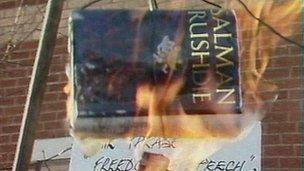

Rushdie said the days after the fatwa were 'a frightening time'

"Not good," he replied.

The book is called Joseph Anton (the pseudonym he used while in hiding, a conflation of the names of two of his favourite authors: Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov) and is written in the third person.

"In a book like this [a memoir]," he says, "you have to be tougher on yourself than anyone else". Perhaps writing "him" instead of "I" provides at least some mental space for critical distance.

And he does, on occasion, paint himself in poor light. Such as the time when he is about to leave Rugby boarding school and is in the process of selling off items of value to the year below. A moment for fond farewells and good intentions one would have thought. Not in the mind of the young Salman, who elects to con a gullible younger boy into paying over the odds for his red leather chair.

For a man upset by what he considers to be an unfair, tabloid-created reputation for being greedy, it might seem an odd anecdote to include. But it serves a purpose, which is to shore up the authorial voice as objective, honest and straight-talking.

The third person voice adds another veil of objectivity to what is a deeply personal, passionate memoir that duly succeeds in fulfilling a central purpose of the genre, which is to settle scores.

Wives, politicians, critics and Penguin - the original publishers of The Satanic Verses - all come in for some stick. As does Roald Dahl. Twice.

"I've waited twenty-three years to say what I thought of [him], he was extraordinarily unpleasant… I think [I have been] quite patient," he says unapologetically.

Rushdie writes of his frustrations working as an ad man, penning tag lines like "naughty, but nice", while watching friends such as Martin Amis and Ian McEwen make forging a literary career look like a (much tastier) piece of cake.

"I hated them," he jokes with the deportment of a contented tortoise that has caught up with not one, but the two talented hares.

The conversation moves on to the repercussions following the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988. Did he know when he was writing the book that it had the potential to be provocative?

"I thought probably that some conservative, orthodox religious people wouldn't like it.

"My view," he continues, "was, and is, that nothing is off limits. When you start writing about the stuff that is the central experience of your own life you can talk about whatever you want, in whatever way you want."

Salman Rushdie's voice is soft, measured: his choice of words frequently precise and pleasurable. He is not a fidgeter, arm-waver or gesticulator. He is physically passive. But he is a fighter who will - and I suspect enjoys - fronting up to anyone on an intellectual battleground.

He describes the days after the fatwa as "a frightening time", when he "was worried about my family. It was very disorientating, very hard to know how to act". The whole affair, he says, "knocked me off balance".

He thinks he might have been wrong to agree to go into hiding; that things might have been better had he stayed at his "perfectly good" home. How did he feel when he saw the vitriolic street protests in Britain?

"It felt horrifying… it worried me a lot that not one of those people was charged with any offence even though they were calling openly for somebody's death every week."

He describes the whole affair as "a first note of the dark music…you could go from that to the 9/11 attacks, there's a more or less straight line between them".

According to the memoir, one of the reasons Penguin executives resisted publishing a paperback version of The Satanic Verses was because they felt the author had not fully explained the potential his book had to offend.

The book's publication outraged hardline Muslims

They argued that he was an Indian from a Muslim family with a first class history degree from Cambridge and detailed knowledge regarding the nuances of the Islamic faith, and was therefore aware that certain passages could be controversial.

Did he ever - in his time spent in isolation - or at any time since, think to himself that he, in any way, helped fan the flames of religious fundamentalism that continue to crackle and spit today?

"No," he says emphatically, "I'm sorry I don't think that. Maybe I'm supposed to think that but I don't think that. I'm very proud of that book… I think maybe it is one of the best books I ever wrote."

He talks about the threat posed by religious extremism to freedom of speech. What does he think is the solution?

"Be braver," he insists. "I think the only way of living in a free society is to feel that you have the right to say stuff."

Few would argue with the sentiment of that statement or fail to recognise that it is in the detail of what is meant by the rather woolly word "stuff", where the arguments, laws and death threats reside.

Sometimes it appears as if there is an assumption that freedom of speech is without issues, that it offers a panacea for society; that it is the easy and obvious option. It is not.

Salman Rushdie knows more than most, the ability to say what you want, when you want, about whatever you want comes with its own difficulties, responsibilities, and with plenty of strings attached.

- Published5 September 2012