The story of West Side Story

- Published

West Side Story made its Broadway debut on 26 September, 1957

Fifty-five years ago this week, a new kind of stage musical opened in New York. West Side Story was based on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet - but its depiction of violence between New York street gangs meant the show was a long way from the typical Broadway fare of the '50s.

The idea for West Side Story came to young director-choreographer Jerome Robbins in the mid-1940s: Shift the Romeo and Juliet story of two warring families to modern New York City. But it was to be a dozen years before the show hit the stage and there were many changes along the way.

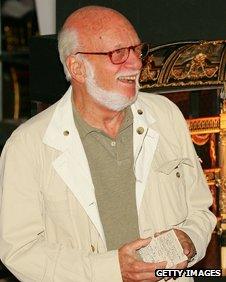

Sitting in his office in the Rockefeller Center, Manhattan, co-producer Hal Prince can recall every detail of how the show emerged.

Hal Prince's other credits include Follies and Sweeney Todd. He was the inspiration for John Lithgow's character in the film All That Jazz

"By the time I came in, Jerry Robbins' ideas had moved on. In the '40s I guess it would have been a rather gentler piece about the love-affair of a Catholic and a Jew - people who weren't slicing each other up with knives.

"But by the '50s New York had changed. In the part of town we used to call Hell's Kitchen [the area was later renamed Clinton] there'd been a sort of race war with attacks on immigrants, mainly from Puerto Rico. Those tensions changed the whole storyline and made it much more dynamic."

When Prince and his partner Robert Griffiths took on West Side Story another producer had already walked away, fearing the material wasn't commercial.

"You know, 55 years ago West Side was an audacious project," says Prince. "People had adapted Shakespeare before but for musical comedies like Kiss Me Kate."

It was the young Stephen Sondheim who called Prince and got him interested in the show. Sondheim, eager to be a Broadway composer, had been prevailed upon to provide "additional lyrics" for Leonard Bernstein's score (eventually he got a full credit).

Prince recalls the first time he heard the score. "It was a Sunday evening at Lenny Bernstein's apartment with Lenny playing the piano very loudly because he was nervous. Steve sang the words. By the time they'd finished, I knew we were producing. We raised the money in 24 hours."

Finger-clicking good

Central to Robbins' concept was that all the cast would act, sing and dance. Martin Charnin, now 77, recalls turning up at an open call at the Broadway Theatre.

"I'd only just left school. I think Robbins and Steve Sondheim had pretty much exhausted the possibilities for finding convincing juvenile delinquents who could also sing and dance. It's kind of niche.

"In truth, I was no great dancer but I moved well and maybe I looked interesting in the James Dean way that was fashionable. Plus, I was a good finger-clicker - which turned out to be a vital skill on West Side."

The musical was Stephen Sondheim's first experience of Broadway

"I was cast as a character called Big Deal: I played him more than a thousand times and I never got bored. When we went on tour, I used to follow a different music part every performance - say the piano part one night, and trumpets the next.

"I used to marvel at Bernstein's music: It was so original. There's never been anything like it.

"When people say to me, 'oh you can't possibly have been in the original West Side Story', I say, 'listen to the cast album Columbia issued. In Gee, Officer Krupke, I'm [playing] the Judge and I can't tell you how proud I am of that moment."

Jerry Robbins, who both directed and choreographed, had a reputation as a fierce taskmaster. Charnin says the reputation was deserved.

"My dance role was limited, so I didn't have the worst time with Jerry but I watched how he could treat people in rehearsal.

"But, funnily enough, Jerry's monster, which definitely surfaced at times, was acceptable. You realised you were in the presence of an extraordinary talent and he knew what he wanted. Jerry was trying to get the best out of you. But, whereas Steve Sondheim and I became good friends, I think everyone found Jerry impossible to get close to."

Something's Coming

Hal Prince recalls that the original reception to West Side Story was mixed, from press and public.

"Some nights we'd have 200 walkouts from the theatre but those who stayed were wildly enthusiastic," he says. "Most reviewers thought the show was clever but cold and lacking in heart."

After its opening season, the show took only two Tony theatre awards, for choreography and set design. Hal Prince says what really cemented West Side's status was the 1961 movie version.

Rita Moreno won a best supporting actress Oscar for her portrayal of Anita in the 1961 film version

"Public taste had caught up with us: The movie swept the board at the Oscars because the style and story no longer shocked."

In total, the film took 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, awarded jointly to Robert Wise and Jerry Robbins (although Robbins had largely been sidelined during production).

"The investors who had done fairly well from the play suddenly made real money from the movie," says Prince. "And the movie was good - though I like to think the stage show was better."

Bernstein, Laurents and Robbins all went on to further success, although none ever had as big a hit on Broadway again. All are now dead. Stephen Sondheim, no longer limited to writing the words, became the most influential voice in music theatre.

Soon after leaving West Side Story, Martin Charnin gave up performing and set out on a long career as a director and lyricist. His big hit came with Annie in 1977.

Prince spread his wings to direct as well as produce and, in his mid-80s, is planning a career retrospective to open next year called Prince of Broadway.

A big musical is always a collaboration and West Side Story united the talents of Bernstein, Sondheim, Robbins, Laurents and Prince at exactly the right time. The initial reception was cool but for half a century it's been acknowledged as one of the classics of musical theatre.

- Published11 October 2011

- Published6 May 2011