JK Rowling on swearing for adults

- Published

JK Rowling: "The idea just came to me, I had that almost visceral reaction when you know you want to do something"

"That's the thing Mark Lawson was most interested in", JK Rowling says, referring to her liberal use of A Very Naughty Word in her new novel, The Casual Vacancy.

I'm not surprised. It gave me a bit of a jolt when I read the book, given that she is world's most famous children's author.

The author, though, seems taken aback by the reaction.

"He's interviewing me for my book launch. I think I'll deal with it head on," she continues, before suggesting her opening line: "So, Mark..." followed by that Class A profanity.

And then she guffaws. An erupting bellow of a laugh that is bawdy and infectious.

I was unsure quite what to expect from the apparently publicity-shy, multi-millionairess and creator of Harry Potter, but I hadn't reckoned on what I found.

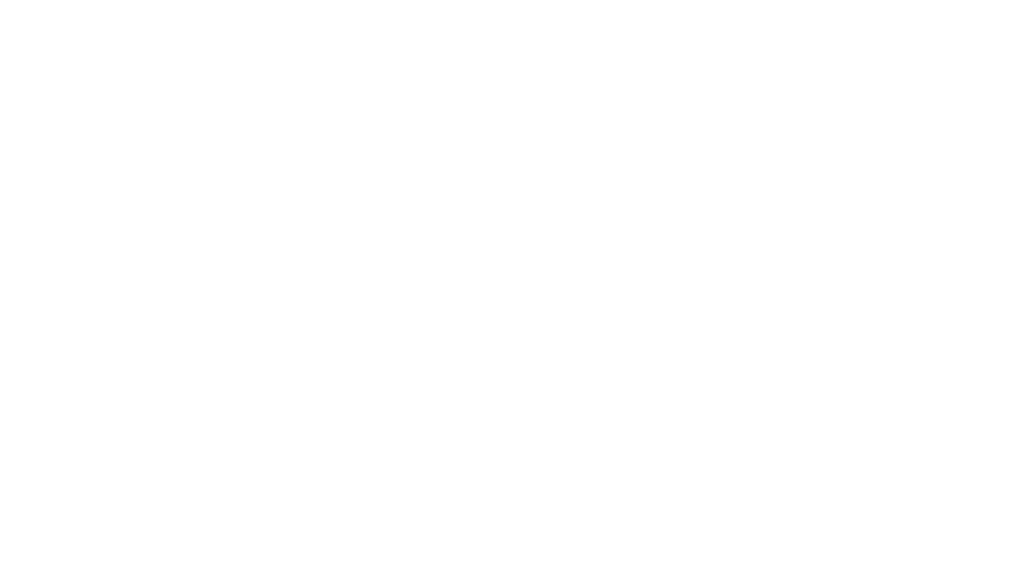

On her own patch (the interview took place in her Edinburgh office), surrounded by her attentive team, Jo Rowling is funny, charismatic and self-deprecating, with a comedian's eye for the absurd.

She's also chatty, open and amusingly indiscreet (off camera) with a joie de vivre and energy that lifts a room.

I had been under the impression that she was the type who was always in the kitchen at parties. If that's the case, then the kitchen is where everybody else would be too.

Shrinking violet? I don't think so.

Which is not to say that the author of a social realistic novel about drugs, death, class, politics and a community fuelled by bitterness does not have a serious side.

Her struggles with depression are well-documented, as are her politically-charged opinions, and understandable fury at press intrusion into her private life. Earnestness is this author's default setting, the hardened shell that protects her from the unknown.

Mine is her last interview in a meticulously planned roll-out of the new JK Rowling brand extension, that of a literary novelist writing for grown-ups.

Chat shows and tabloids have been eschewed, public appearances have been limited, and media interviews given only to the upmarket arty crowd: Radio 4's Front Row, BBC Two's Culture Show, The Guardian... and me, as the man from the BBC News At Ten and the Today Programme.

She walks briskly into the room, announces that she is ready but then goes to fiddle with something on the windowsill. She sits down, looks for a clip-on mic and quips to the cameraman, "could you make me look 10 years younger?". She's a bit nervous. We both are. We have an awkward exchange, a sort of pre-interview verbal fumble.

And then she settles, and I see her eyes.

Now, I've met plenty of people with blue eyes - some of whom, like Robert Redford, are famous for them. But I have never ever encountered a pair of electric blue peepers like JK Rowling's. It's as if a couple of azure coloured crystals have been installed in her head - and then back lit for dazzling effect. So much so I wonder if they are getting a little contact lens "help".

"No," she confirms, "but thank you".

Must be the lighting, then. Or perhaps they're being set off by the blue Stella McCartney (drainpipe) trouser suit she is wearing, which itself is being set off by a pair of black stiletto ankle boots. She looks more like a kick-ass businesswoman, not - as I have read - a left-leaning creative type with little interest in the commercial side of things.

'Killer question'

The interview is sticky to start with. My inquiries are answered politely and assuredly, but without much passion. She is wary. Been caught out too many times, she laments, by going on the record about what book she is writing next, only to feel bound by her utterances.

Therefore I get "my next book will almost certainly be for children". It's basically finished, she says, and will be aimed at a younger audience than the Potter series.

Fair enough, I won't hold her to it.

And so we continue, like a misfiring engine.

Until, that is, I make a complete hash of what I had hoped would be a killer question.

Rowling still receives fan mail from around the world every day

As we all know, one of the more basic technical requirements of an interviewer is the ability to ask short, concise, well-crafted questions. John Humphrys once told me he starts with "why?" and only expands further if he feels it is absolutely necessary.

I, on the other hand, choose in this instance to ask a long-winded, ill-conceived, mildly offensive, rambling question that ended "…like a primary school teacher becoming a rock star".

"I'm sorry," says the bemused writer, "I don't understand what you are asking". She is being generous; the twitching muscles around her mouth indicated a laugh being suppressed with the utmost difficulty.

"Have you ever seen Breaking Bad?" I ask awkwardly.

"No," she says.

"It's about a school teacher- a Mr Chips type who becomes a crystal meth dealer."

She explodes with laughter.

"I see," she says, hugging herself. 'So I'm Mr Chips who's now selling crystal meth?"

I'm not. Having read the book (I'll write more about it on my blog tomorrow when the fiercely enforced embargo has been lifted), nothing could have been further from my mind.

I was trying to ask if she had purposely - self-consciously, even - used profanities in the first 30 pages (and plenty thereafter), to shock the reader (and herself?) out of approaching the novel as a book by "JK Rowling - children's author". Was she in fact, Breaking Bad?

"No", she says, she wasn't.

A very short answer to a very long question. An answer I am not wholly convinced by, but the moment to press any further had been lost. And, besides, a Rubicon had been crossed. We both relax - JK Rowling becomes Jo, an everywoman to whom extraordinary things have happened (not unlike Harry Potter's fictional experience, ironically).

She then tells a story that sheds light on how becoming a "brand" has affected her thinking and decision-making.

I ask why she chose Little Brown to publish The Casual Vacancy. Because, she says, David Shelley, an editor at the publishers with whom she had had lunch prior to signing the deal, was on her "wavelength".

"What did he say, and you say, that made you feel, yes, this is sympatico?" I ask.

"He said some things that made me think he understood what I was trying to do."

"Such as?"

"I can't really reproduce it. It was a very interesting conversation because he didn't know I had a book... There were things he said that I knew meant he would understand exactly why I was writing it and what I was doing'.

That was an unusual thing to say. Is there a set of code words that crack Jo Rowling? Speak them and you're in, accepted, trusted. If so, I'm intrigued to know what they are.

"Very specifically" she says, "he knew the Potter books very well.

"We had certain conversations about characterisations and political themes. I hadn't told him that I'd written a book for adults [but] he started talking about 'why aren't you?'. And then we had whole conversation about the fact that I had."

He told her what she wanted to hear, he believed in her.

The author says she is "proud" of her new book, but "nervous" about its reception

And she believed him.

Knowing who to trust, whose advice to take and who to believe becomes increasingly difficult the richer and more powerful you become. Finding people to tell you the truth becomes harder.

It's a theme she explores in The Casual Vacancy, through a teenage character that craves authenticity, who is despairing of those around him for allowing themselves to be compromised, leading to their every word and deed being, to some extent, fake.

That is why for all her success and apparent happiness she continues to be so guarded and can appear as chilly as Edinburgh on a September night.

But behind the money, the management and the brand, I found a person who is like most of us: An insecure worrier who cares about the world in which she lives.

And who, when the pressure is off, likes nothing more than a filthy laugh.

- Published26 September 2012

- Published26 September 2012