Thelma Schoonmaker: The woman behind Martin Scorsese

- Published

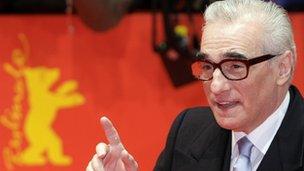

Thelma Schoonmaker has edited all of Scorsese's feature films since the Oscar-winning Raging Bull in 1980

The name Thelma Schoonmaker may not ring a bell with everyone, but as Martin Scorsese's three-time Oscar winning editor, she is one of the most trusted names in film editing.

Having met Scorsese "by accident" in 1963, the duo have produced some of the most critically acclaimed films of the past 30 years, including Raging Bull, Goodfellas and The Aviator.

Scorsese also introduced her to her late husband, the British film director Michael Powell, whom she was married to for six years until his death in 1990.

The BBC caught up with Schoonmaker, 72, to hear about her experience working with one of the greatest filmmakers of the 21st Century, and their side project to restore the classic films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger to their original Technicolour glory.

You obviously bring a mass of technical skill to your job as editor, but working with the same director - one as significant as Scorsese - for more than three decades, presumably you've built up a very personal relationship with him.

All great directors or anyone who has a strong vision like Scorsese needs to have a lot of support around them. I think from the very beginning - when we met each other - he realised he could trust me to do what was right for his movies.

Scorsese was deeply influenced by the films of Powell and Pressburger

[Rather than] making a name for myself, I would be hand in glove with him in terms of carrying through what he tries to lay down when he shoots.

He says I bring out the humanity in his films. I don't think that's really true - he lays it down there - but I think as a woman, perhaps I'm more tuned in to emotional things in the films that maybe I pull out more.

We work as a team and I understand what he is trying to do and what he approves and disapproves of in terms of acting.

He has this thing about eyebrows. He thinks [they] are too easy a thing for actors, so he discourages the use of eyebrows too much. That's the kind of depth and it's that kind of thing that - over the years - you learn.

Scorsese's work with actors often involves giving them the freedom to improvise and deviate from the script, so does this complicate your job?

The film we're filming now is called Wolf of Wall Street and it's filled with improvisation. He's being very brave in the way he's using improvisation and the actors are having a hell of a time coming up with great original humour.

He loves working that way; taking this rich ore and mining it and shaping it as they're shooting.

Then I have to deal with all the problems that causes because things don't match. But that's not important, what's important is to get the power of the scene across and don't worry about whether things match, or find another way to get around it. It's such fun!

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was one of several masterpieces by Powell and Pressburger

What was it about Powell and Pressburger's 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp that made you and Scorsese feel it deserved to be brought back to life?

We've both seen the movie over and over again and we both feel so deeply about it. It's a very unusual film, you never know what's coming next. It portrays people and the way life buffets them in an extraordinary way.

You go through the main character understanding very early in his life that he's lost the woman that he loves because he doesn't realise he loved her until too late. She gives him the signals but he waits too long and another man marries her.

That sadness and sense of loss pervades the rest of the film but not in a way that makes you feel bad. It's examining something that many people feel in life all the time.

What did Scorsese bring to the project?

Scorsese was so deeply influenced as a film maker by [Powell and Pressburger] and the fact they were so unusual and never cliched or sentimental.

His commitment is to restore every film that needs it. My husband said the first time he met him he couldn't believe this young director knew every shot [he'd] ever taken and the blood started to run in [his] veins again. They had a wonderful friendship and [Scorsese] brought him back to the world.

You were involved with the project to remaster The Red Shoes, Powell and Pressburger's classic 1948 film. What challenges are associated with restoring old films renowned for their mastery in Technicolor cinematography?

Some of the film was covered in mould, a common problem that occurs in archive. The mould was actually eating into the emulsion of the film.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp dramatises the trials and passions of a lifetime in the military

But the result [of the restoration] is that Blimp has become alive, it's so vivid. That vividness has brought the humour to the fore, a loving examination of bureaucrats and the strange people who made up that world at the time.

Instead of just being plainly satirical or savage, it's an understanding portrayal of what these people were like at this time.

Despite making influential films through the 1940s and 1950s, Powell and Pressburger were lesser known than their contemporaries such as Alfred Hitchcock.

Their films were very unusual, every film was different and my husband said the reason critics didn't support them as well as they should have was because they had to go in and engage with the film, they had to experience something new and when they were writing eight reviews a week, it was a bit annoying.

Now, [their films] are considered masterpieces, but at that time people thought they might have been a little too weird, too emotional.

The other thing is they never spent any money on self publicising themselves. They were too busy making movies. David Lean and Hitchcock had big Hollywood publicity machines behind them.

A special restoration edition of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is available now on DVD and Blu-ray.