HMV: How the top dog lost its bite

- Published

HMV has had a shop on Oxford Street since 1921

Philip Beeching was uniquely placed to witness the rise and fall of HMV, which is set to go into administration.

Beechwood, the advertising firm he set up with John Wood, handled the record store's advertising account for more than two decades, from its 1980s heyday to the dawn of iTunes.

He documented HMV's trials and tribulations in an article on his personal website, external last year. In this updated version, he brings the story up the present day.

I first started work on the HMV advertising account in 1982, little knowing that I would go on to handle this piece of business for over 25 years and in that time work with six marketing directors and four managing directors.

What I also didn't know is that my path was crossing HMV's at the dawn of a golden period for the record retailer.

I say record retailer because that's what it was back in 1982, a retailer of records made of vinyl.

What was to make HMV a hugely profitable company lay just around the corner, namely CDs and video.

HMV stands for "His Master's Voice". The company's logo is Nipper the dog, listening to a vintage gramophone

The invention of CDs meant we all wanted to replace our record collections with wonderful new shiny, "indestructible" CD' and we were all happy to fork out £16 or £17 for each one; it also became de rigeur to have a library of videos prominently displayed in the corner of your living room.

In fact, CDs were to deliver such an incredible profit margin for HMV that the House of Commons set up a Select Committee to investigate these bumper profits and the then-CEO, Brian McLaughlin, got a serious grilling but ultimately nothing was done to the pricing structure.

The advertising strapline we created, which sat alongside the iconic image of HMV's mascot, Nipper, listening to the gramophone was "Top Dog for Music" and that's exactly what HMV were. Record companies kowtowed to this all-powerful retailer, offering up millions of their own money to contribute to HMV's "co-operative" advertising.

What choice did they have? This was the only way they had of getting their products in to the hands of the consumer. This "co-op money" was to become a drug which would always prevent HMV from spending their own marketing money and undertaking any genuine brand advertising.

A shop for the King Of Pop

The store expanded around the world - into the USA, France, Germany, Canada and Japan. In 1986, it opened what was then the world's largest record store in London's Oxford Street.

I remember the opening ceremony well. It was being jointly performed by Bob Geldof and Michael Hutchence; there were literally tens of thousands of people in attendance and Oxford Street was closed (liaising with the police for all new store openings in the 80s and most of the 90s was essential, such was the pull of HMV and the music stars they could attract for a personal appearance).

We all stood expectantly by the red carpet at the front of the store as Bob Geldof's limousine pulled up - but when he discovered he was the first to arrive, he told his driver to circle the block, as he didn't want to be upstaged by Michael Hutchence.

Five minutes later Hutchence's limo arrived and when he learned he was now the first to arrive, he told his driver to circle the block as he didn't want to arrive before Geldof. We stood there, not knowing what to do as their cars went round a second and then a third time before we negotiated a peace accord with their management and they pulled up and got out at the same time.

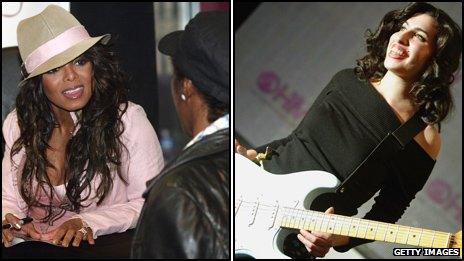

The chain could attract stars like Janet Jackson and Amy Winehouse for signings and in-store performances

This was also to be the shop that, when Michael Jackson was in town, would be closed down for him to browse in private, and I remember glimpsing him wandering through the empty aisles of a ghost-like megastore.

It just kept on getting better and better for HMV as computer games arrived, along with DVDs. The stores and profits went from strength to strength. Such was the heady feeling of success that HMV would get together all of their store managers and head office staff for a three day "conference" every year, which was two and half days of fun and partying and a half day of presentations by the board.

Now, we're not talking Bournemouth or Bognor here. It was usually somewhere exotic like Turkey or Spain. I remember a five star hotel in Marbella when Billy Connolly was the surprise cabaret act and everything was free for everyone, from watersports to the watering hole of the beach bar.

This engendered amazing loyalty from the music fanatics who were the store's managers, as well as a feeling they really were beating Richard Branson's Virgin Megastores (remember them?)

The rivalry between the two retail giants would make a book in itself, with Branson turning up with suitcases of cash to try and gazump HMV for prime city centre shop locations.

But if HMV's executives had looked out from that luxury beach hotel in Marbella, they might just have seen a few dark clouds forming on the horizon.

HMV continued to expand throughout the 90s - up to 325 stores, They bought the book chain Dillons, and later Waterstones, a further 195 stores, and in 2002 they floated on the stock market for a £1 billion valuation and a share price of £1.92.

Today its value will be determined by the administrators - but that's only if they can find a buyer.

'Just a fad'

Not long after HMV's stock market listing, Beechwood, (the agency I founded and ran with my business partner, John Wood) was asked to re-pitch for the business as a new marketing director and managing director had come in to the company.

As I had worked on the account for so long and felt it was in my blood, I really wanted to give it my all, so we pulled out all the stops in this five-way pitch.

The day of the presentation came and we stood in the boardroom in front of the new MD, Steve Knott and his directors. For some time we had felt the tides of change coming for HMV and here was our perfect opportunity to unambiguously say what we felt.

The relevant chart went up and I said, "the three greatest threats to HMV are, online retailers, downloadable music and supermarkets discounting loss leader product".

Suddenly, I realised the MD had stopped the meeting and was visibly angry. "I have never heard such rubbish", he said. He accepted supermarkets were "a thorn in our side" but not for the serious music fan.

"As for the other two," he continued, "I don't ever see them being a real threat. Downloadable music is just a fad and people will always want the atmosphere and experience of a music store."

It's important to remember that the dotcom bubble had just burst and many people were mistaking this stock market meltdown for an internet meltdown. As we sat reflecting in the pub afterwards we felt decidedly winded by his onslaught - but a few weeks later we were to discover, somewhat to our surprise, we had held on to the business. Virtually none of what we recommended ever saw the light of day but sometimes during difficult times clients simply want the comfort blanket of what's familiar.

HMV's boss says he is confident of finding a solution to the retailer's troubles

Regrettably for HMV our three predictions came true to an extent we could never have envisaged and by 2006, a new MD Simon Fox was brought in to try and sort out the ailing company.

Throughout the late 90s and right up until today, HMV's single biggest mistake has been a lack of investment in their online offering and unfortunately it's a mistake Simon Fox continued to make.

He chose to try and diversify into electronics (a business that was already failing on the high street) and entertainment through venues such as the HMV Apollo, which subsequently had to be sold off along with Waterstones to pay down debt.

Fox has now left the company and been replaced by Trevor Moore, (who somewhat ironically came from Jessops). I was surprised that the press let Fox off relatively lightly but, in truth, the damage was done in that late 90s period, well before he arrived, when we could clearly see what was developing with the internet (we started one of the first digital agencies in London which we later sold to a US group), yet HMV's efforts were at best a token gesture.

This lack of online investment and risk aversion may well stem from a disastrous and expensive foray in to conventional mail order in the early 90s when HMV Direct was set up and later folded.

Who was better placed to exploit the internet than HMV? The power of the brand, their heritage in music, their unrivalled access to content from film, game and music companies. Who would now have been better placed to take advantage of social media?

Hubris, arrogance, a feeling of invincibility. Companies fail for many reasons and there was probably a little bit of all three involved with HMV but ultimately they were simply overtaken by the march of technology faster than they could ever have imagined.

By the time they had started trying to reinvent themselves it was too late. They were no longer "Top Dog".

Philip Beeching was in advertising for over 30 years, working at some of the UK's biggest ad agencies, including Ogilvy, Allen Brady & Marsh and Yellowhammer. He started his own agency in 1989, which later became Beechwood. Philip is now retired and blogs on the world of advertising and marketing from his home in Brazil.