Obituary: Jonathan Miller

- Published

Jonathan Miller's talents were manifold, his natural gifts bewildering in their profusion.

He was a humorist, an author, a director of films, TV, plays and operas. He was a photographer, a sculptor, an all-purpose intellectual and accomplished broadcaster.

He could be witty, charming and life-enhancing, especially when he was the centre of attention, as he usually was.

Yet Sir Jonathan - as he became - was also famously cantankerous and grumpy, and on occasions devastatingly rude.

He claimed his chronic dissatisfaction stemmed from an early decision to make his career in the world of the arts and entertainment, rather than science and medicine.

Others thought it had something to do with attention-seeking on the part of a very clever person deprived of affection during his childhood.

Beyond the Fringe

Jonathan Miller was born in London in July 1934. His father Emanuel was a distinguished child psychiatrist; his mother Betty was a novelist and biographer.

But neither, by Miller's own account, was especially warm or affectionate.

Jonathan Miller with the Beyond the Fringe team: Dudley Moore (seated), Alan Bennett and Peter Cook.

He was educated at St Paul's School - where he was reputedly talkative and entertaining - and at St John's College, Cambridge, where he read medicine.

He might have become a leading neurologist were it not for the extraordinary success of the groundbreaking satirical revue, Beyond the Fringe.

It premiered at the 1960 Edinburgh Festival, and brought a kind of clever undergraduate humour to a much wider audience. It transferred to the West End and then to Broadway.

Miller had just qualified as a doctor, and taken leave from his job to travel to Edinburgh. The show was a runaway success, and it was instantly apparent that he faced a choice.

He found performing intoxicating and addictive. He later described that first Edinburgh run as "a cocaine-like snort of celebrity and approval".

But, in the words of his biographer Kate Bassett: "He could not both walk the wards and tread the boards."

In the event, he signed up for the show's West End run and put his medical career on hold. In later life, he often claimed he was sorry.

Miller would probably have become a leading neurologist, had it not been for his talent for comedy.

Going into show business was like "stepping off the edge of a diving board into this murky swimming pool where my moral fibre rotted irreversibly. I still fiercely regret the distraction. I think that was a bad thing I did."

Directing Alice

By 1965, he was working in television - as the editor and presenter of the BBC's arts programme, Monitor.

The following year, he directed a controversial television version of Alice in Wonderland. It was rather like a 1960s acid trip with John Gielgud as the Mock Turtle.

The programme was denounced in the House of Commons as a perversion unfit for children, and added to Miller's burgeoning reputation for being excessively trendy and pretentious.

Jonathan Miller with 13 year-old Anne-Marie Mallik - who played Alice - during filming in 1966.

He directed Whistle and I'll Come to You - a TV ghost story starring Michael Hordern and began to forge a reputation in the theatre.

His 1970 production of The Merchant of Venice starred Laurence Olivier. The grand old man of British theatre wanted to play Shylock as a traditional Jewish stereotype - complete with false nose and teeth.

Miller urged him to throw away the props and play the part as a 19th Century businessman - who happened not to be a gentile.

It reflected Miller's own approach to his background as a non-practising non-believer: "Not really a Jew... Jew-ish," to quote a line from Beyond the Fringe.

From 1973 to 1975, he was an associate director of the National Theatre, which was then run by Olivier. But when Olivier retired, the top job went to Peter Hall.

The two men fell out. Miller dismissed Hall as "a safari-suited bureaucrat". Hall retaliated, describing Miller as both a genius and a fool.

"Jonathan did very unsuccessful work," he said, "and there's nothing to breed discontent like failure."

Public intellectual

In 1980, he joined the BBC's then-troubled project to televise all of Shakespeare's plays. He directed six of them, including The Taming of the Shrew with John Cleese and Othello with Anthony Hopkins.

Anthony Hopkins and Bob Hoskins in Jonathan Miller's production of Othello.

But the yearning to return to medicine stayed with him. In 1978, he presented - in his inimitable fashion - a TV series about the history of medicine and anatomy, The Body in Question.

"And so, over millions of years," runs a typical line from the script, "the head has developed as a far-seeing helmsman which guides and controls the propulsive engine of the rear end."

It was clear that he still regretted that decision not to become a doctor. "There are things about the sciences which are difficult to do," he said on Desert Island Discs in 2005.

"You have to wrap a wet towel round your head to think out some of the things. It sounds like an idle and arrogant boast - most of the things I've done in the arts I can do with my right hand tied behind my back."

He did eventually returning to medicine full-time, spending two years at McMaster University in Canada, and as a research fellow in neuropsychology at Sussex University. But it didn't last.

Cutting-edge science, as he acknowledged, was beyond him: he'd been away too long. And it turned out that he craved the limelight after all.

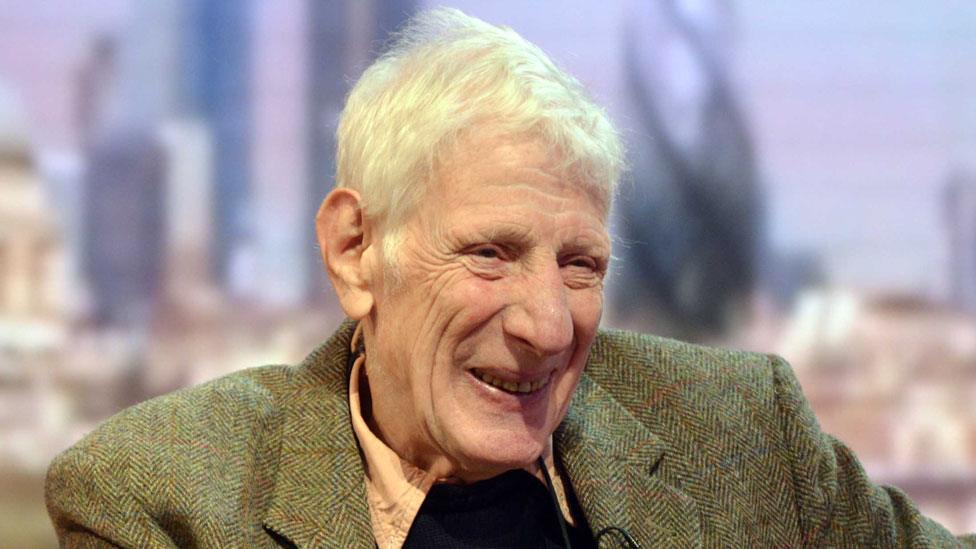

Jonathan Miller presenting The Body In Question in 1978.

Monumentally tactless

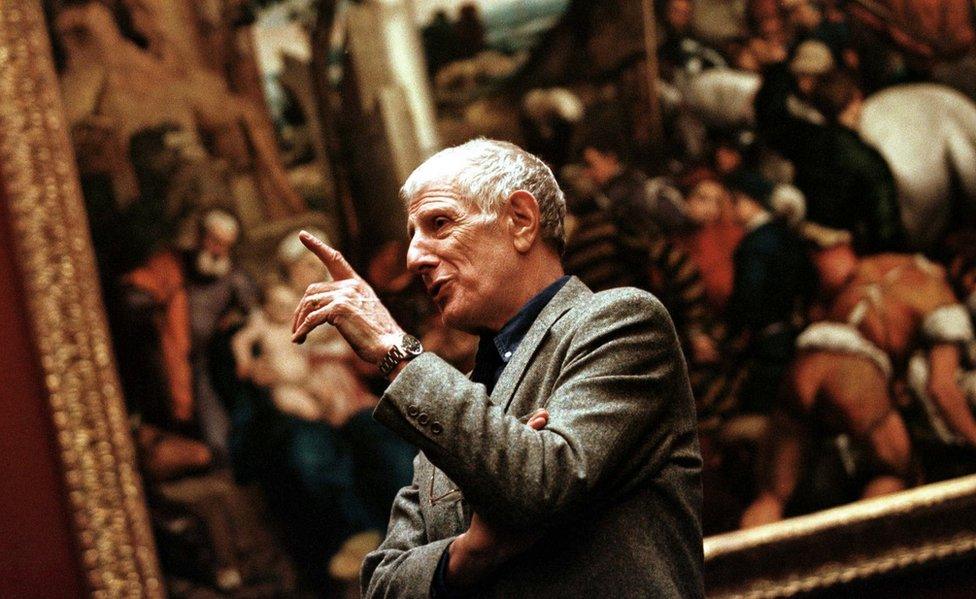

He returned to run the Old Vic for a year, to his role as a kind of public intellectual and to a life of writing, broadcasting and directing - especially operas.

He'd staged his first opera, Mozart's Cosi Fan Tutte, for Kent Opera in 1974, despite being unable to read music.

Over the next four decades, more than 50 further productions followed at opera houses around the world. At one point, he was working on six international productions simultaneously.

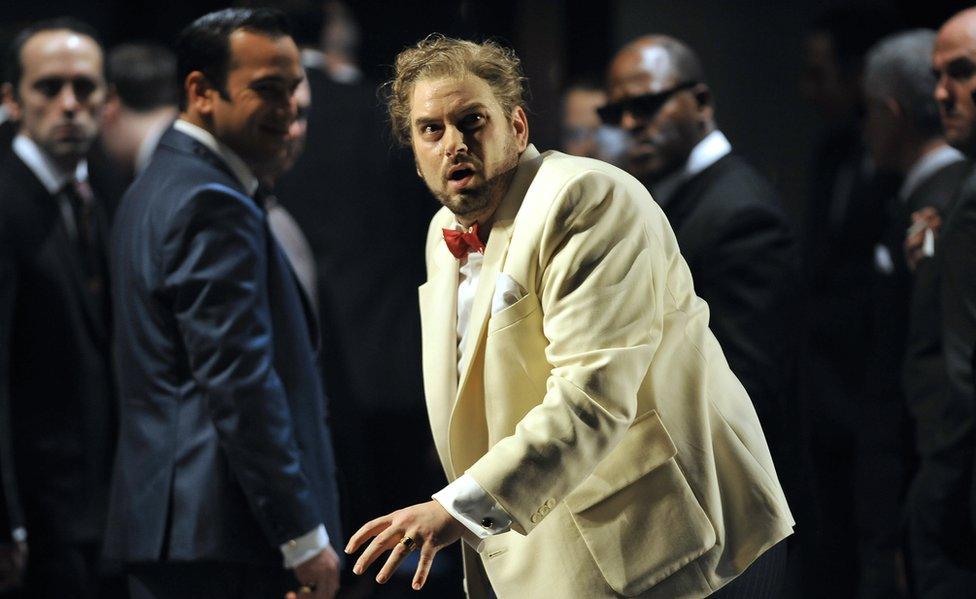

Several of his productions were so successful they were repeatedly revived. His Mafia-style production for ENO of Verdi's Rigoletto, updated to New York in the 1950s, remains in the repertoire.

His production of Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado was equally successful, although he claimed to hold them both in contempt. "Boring self-satisfied drivel," he called their work. No better, he claimed, than "UKIP set to music."

Jonathan Miller's production of Rigoletto for the English National Opera was revived many times.

The critics didn't always like his work - and Miller often displayed a thin skin. But that didn't stop him dishing it out to those he didn't like.

Opera singers of the old school (people assumed he had in mind Domingo, Carreras and Pavarotti) were derided as "Jurassic performers", who arrived at rehearsal "with shreds of primeval vegetation hanging from their jaws".

And Britain under Margaret Thatcher was described as "an ugly, racist, rancorous little place... a mean, peevish little country... with its acid rain of criticism and condescension."

He could be personally kind and thoughtful, but also monumentally tactless. The Royal Opera House, which commissioned several of his productions, was "a kind of wife kennel" for rich men.

A large part of the audience for his work he described as "disgusting old opera queens" - this from a man who had been a vice-chairman of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality.

He continued to present television series - on language, madness and atheism - though the last was a term he objected to.

"I never use the word atheist of myself," he said. "It's scarcely worth having a name for. I don't have a name for not believing in pixies."

His versatility made him a figure of fun. Private Eye mercilessly satirised him as the self-important Dr Jonathan, a sage and a pseud and too clever by half.

Jonathan Miller was often called him a Renaissance Man and a polymath - both terms he loathed.

In later life, he became increasingly curmudgeonly. A newspaper profile described him as "famously, noisily, angrily fed-up".

He complained that he'd always felt undervalued in Britain, that he was no longer being offered work, that he was assumed to be dead and that he was giving up directing opera.

He was awarded him a CBE in 1983 and a knighthood in 2002. He never carried out his threat to leave the country, turning to making sculptures out of scrap metal instead.

Erudite and clever, witty and paradoxical, Jonathan Miller was a born performer, a brilliant talker and a first-rate director.

He will be remembered as a man, who even at his grumpiest, couldn't help being entertaining.

- Published27 November 2019