Children's TV veteran reflects on career

- Published

Geoffrey Bayldon (top centre) with the rest of the Catweazle cast

Was children's TV really better in your day? Joy Whitby should know. The award-winning producer of Play School, Jackanory and Catweazle has enjoyed a career in children's factual, drama and animated films that has spanned six decades at the BBC, ITV and Channel 4.

Still working today, at the age of 82, she's preparing to give a talk at the British Film Institute about a lifetime of telling stories on television.

In 1964 Whitby was asked to create a new programme, aimed at preschool children, for a new channel - BBC Two. They called it Play School and it ran until 1988.

"Watch with Mother had some lovely characters but was past its sell-by date, I thought," says Whitby, who started out telling stories to the young children of psychiatric patients at the Mayfair Delinquency Clinic, where she was a secretary.

After joining the BBC, she was asked to write a report about their shows for young people. "Children were addressed collectively, as if sitting on your own you would be aware of all the others watching in their own homes," she recalls.

In addition, "many of the programmes were written by puppet performers to showcase their puppets. They weren't necessarily good writers".

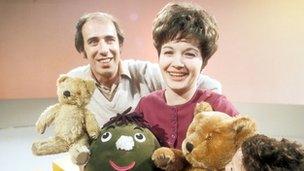

Canadian Rick Jones, pictured with Julie Stevens, was one of the first Play School presenters

Whitby was a rarity among women in TV back then - a young, married mother with three small children of her own. But she developed basic principles that, nearly 50 years on, we take for granted - such as addressing one child only and giving them a close-up view of the action.

"It's like watching an egg hatch. As a very small child you want to see it yourself, not watch other children seeing it."

Play School pioneered diverse casting, both in gender and race, from its earliest episodes. Canadian Rick Jones, who went on to make Fingerbobs, Paul Danquah and Italian Marla Landi were all in the mix.

Whitby's consistently strong record in spotting new talent is notable. Her discovery of Brian Cant's unpretentious charm remains the template for children's casting.

Years later, she discovered Helena Bonham Carter and gave her a role in the 1983 supernatural drama A Pattern of Roses.

She says her programmes were "influenced by advertising - to make tiny ad-type inserts on cleaning your teeth, or eating fresh fruit".

'Too American'

It was those ads that the creators of Sesame Street picked up on when they launched their own show.

Interestingly, Whitby had wanted to use Jim Henson's Muppets on Play School and was disappointed when the BBC turned down the chance to show Sesame Street because it was "too American".

Whitby's prior experience in a photography library and as a radio studio manager meant she saw the power of strong graphic visuals and sound effects to hold a young viewer's attention.

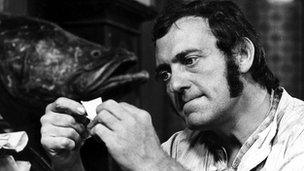

Steptoe and Son star Corbett was among those Whitby persuaded to appear on Jackanory

That experience served her well when she was asked to fill another 15-minute tea time slot on BBC One, which became Jackanory.

A pure storytelling format, like Play School the programme sought "to bridge the gap between privileged children and those who didn't have someone to read to them".

What is Whitby most proud of? "Having persuaded really talented people from the mainstream to engage with children's programming because it helps to notch up the quality," she says.

We take it for granted that writers and stars wanted to be on Jackanory. But it was Whitby who started it by wooing the Edwardian novelist Compton Mackenzie and veteran actors such as Margaret Rutherford, Wendy Hiller and Harry H Corbett to take part in her programmes.

Encouraging children to read has been a lifelong passion. She was the first TV producer to win the prestigious Eleanor Farjeon Award for services to children's literature and she adapted with changing times.

Her 1979 Yorkshire TV show The Book Tower still captivates. Its first mysterious proprietor, Tom Baker, came down the spiral staircase grinning: "I haven't read all of them… yet."

In the first episode, Baker read an extract from a contemporary novel about a boy caught up in a plane hijacking.

'Sense of occasion'

And then, having poured a cup of tea, he opened the pot to take out two live mice in his hands as a prop for the next story.

"What?" you think, watching it today. "Terrorism? Health and hygiene horror?" The paranoid forty-something parent might want to grab anti-bacterial spray and wipe the screen immediately.

But an eight-year-old child still grins in delight. Mice! In the teapot! It's a shocking illustration of how sanitised much children's content has become.

When regularly scheduled children's programmes recently disappeared from BBC One and Two altogether, Anne Wood, creator of the Teletubbies (who originally trained under Whitby) condemned the decision as "ghettoising" children's content.

Helena Bonham Carter, now 46, was 16 when she made A Pattern of Roses

Whitby disagrees. She says she's only concerned about the "glutting" effect of all-day channels. "What's gone is the sense of occasion. You waited and it was your time."

But could children's interests suffer when their dedicated programmes disappear from the shared space of the main channels?

Ofcom has in recent years censured ITV for showing very violent episodes of The Midsomer Murders in what had been the after-school slot.

And as recently as December, the broadcast regulator criticised the BBC for using a 13-year-old actor in violent torture scenes in the crime drama In the Line of Duty.

Young people are more rarely seen on the main channels now, except as fodder for Young Apprentice or Britain's Got Talent.

'Worthless' cartoons

Whitby has never called her viewers "kids" - she thinks it's disrespectful. But looking back over old shows, she notices what's dated.

There are some posh accents here and there. And the pace of editing in some of her earlier dramas can seem very slow to modern attention spans.

1983's A Pattern of Roses, first shown on Channel 4, also highlights an accusation Whitby has had to deal with over the years - that some of her programmes were "too middle-class".

The plot focuses on a public school boy (originally to be played by a very young Hugh Grant) convalescing in a country cottage while waiting to take up his place at Oxford.

He rebels by saying he wants to go to art school. It's hard to imagine such character motivation getting much sympathy now.

Looking back on nearly 50 years in children's TV, Whitby has remained good friends with the performers and writers with whom she worked.

Whitby says Tom Baker was "one of the most exciting" people she worked with

Tom Baker, she says, "was one of the most exciting"; former Rutle and Bonzo Dog Band member Neil Innes "one of the most creative"; and Tim Brooke-Taylor "one of the nicest".

An intriguing revelation is how Verity Lambert, fresh from the huge success of Doctor Who, rang her up to ask for a job on Play School, which had just launched.

A surprised Whitby said "no" to such an over-qualified and high-powered producer.

For now, Whitby is focused on finishing Mouse and Mole, an animated Christmas special with the voices of Alan Bennett, Richard Briers and Imelda Staunton for the BBC.

"Things move on," she says. But she adds that she wouldn't now leave a child under five in front of the television unsupervised if she could help it.

"Many of the cartoons are worthless," she concludes.

"It really is passive viewing, as opposed to the creativity involved in building a castle out of bricks."

Joy Whitby will be in conversation with Samira Ahmed on 2 February at BFI Southbank. The event will be preceded by Joy Whitby: Telling Stories on the Telly, a selection of episodes from some of her best-known shows.

- Published19 January 2013

- Published1 March 2012