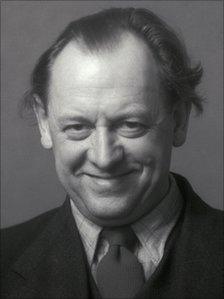

Kurt Schwitters: Portrait of a starving artist

- Published

Kurt Schwitters was driven out of Germany during World War II

German artist Kurt Schwitters was one of the fathers of modern art - but he spent his final years living in poverty and obscurity in the English Lake District.

With his one-man art movement Merz, Schwitters has influenced artists from Robert Rauschenberg to Damien Hirst and Sir Peter Blake and is now the subject of a major exhibition at Tate Britain.

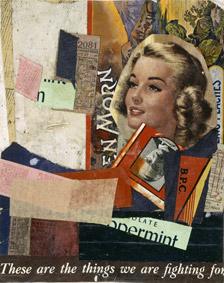

His collages, made from fragments of magazines, discarded bottle tops and other detritus, influenced pop art, while his groundbreaking Merz installations took over entire rooms. He was working on his final creation, the Merz Barn near Ambleside, when he died in 1948.

Few locals were aware of his status in the art world, according to his friend Jo Clarke, now 93, who recalls giving him bread because he was so poor.

How did you meet Schwitters?

We literally bumped into each other. It was just before Easter 1947. I was newly released from the RAF and consequently I was interested in aircraft. There was an aircraft going over and I looked up.

Kurt was interested in bits and pieces in gutters, anything that he could use in his Merz. So he was looking down in the gutters.

He was a large man. Large hands, large feet. As we bumped, he instinctively knew that he was going to knock me over.

So he grabbed me just below the elbows and lifted me high up into the air. And as he let me gently down, as our faces passed, he grinned at me, and that was the start of a good friendship.

It was pure friendship, nothing more than that. The other reason he was attracted to me was that bread was rationed. He had a big frame, needed a lot of feeding, so one of the first things he said to me was, 'Have you any food in your rucksack?'

I had a bit and this big hand pushed it all into his mouth and it was gone in a second. He said, 'I’ll see you again.' So the next time, I saved more food. This time it was a sandwich and he said, 'I like bread, I really like bread.'

The cafes in those days had to account for every slice of bread but it didn't seem to matter what happened to crusts. So there was a big black market in bags of crusts. I was already acquiring one of these each week for my mother so that order went up to two and I managed to see that he got extra bread supplies until he died.

So he wasn’t making much of a living from his art?

No - the lady who was in residence at the Bridge House in Ambleside used to let him, on Saturdays and Sundays, put drawings and paintings on the steps.

These would start off at five shillings on Saturday morning. By Sunday night they were down to sixpence. So in those days it was possible to get a Schwitters landscape for sixpence.

I didn’t like his landscapes at all. I liked his collages but most of all I liked his portraits. But he hated doing portraits. He would never do a portrait unless he was forced into it.

Kurt Schwitters, En Morn 1947. Photo: Centre Georges Pompidou, Musee national d’art moderne Paris/DACS

The residents of Ambleside soon twigged on to this so they lent him money and then suddenly needed it back. Of course he couldn't produce it, so he was forced to do a portrait. At that time, these [portraits] were all over Ambleside. By the '60s, traders had come up from London and most people were persuaded to part with them.

He didn't really talk art much to me, apart from the barn. He was very interested in the barn. I think he knew he wasn't well and he wouldn't last long and he was absolutely obsessed with that. That was why he didn't like doing the portraits, because it took time off the Merz.

Were people in Ambleside aware that he was such an influential artist?

Most people referred to him as 'that foreign fool'. He shuffled. He didn't pick his feet up. He knew he was tall so he walked slightly bent, making himself smaller. So he didn't present very well.

His clothes never actually fitted. They were either too short or too long. I don't know for sure but he gave the impression that he always wore hand-me-downs.

The gentleman who ran the local cafe would give Kurt sheets of wrapping paper, and this was like gold dust to him because normally he worked on bark or something he could pick up.

If there was a rotting animal in a field and there was some washed-clean bone, he would work on that. The locals wouldn't buy that, even for sixpence.

Schwitters planned to transform the Merz Barn in Elterwater, Cumbria into a modern art grotto

Was he in poverty?

Yes he was. He was forced out of accommodation that he possibly could afford because of the damp. This had grave influences on his health. He should have moved a lot earlier, he might have lived quite a bit longer.

What kind of a person was he?

He was a very jolly person. He loved society. He liked a crowd. An audience of one was fine but an audience of 20 was 20 times as good.

There are stories of him standing up in pubs and recounting his avant garde poetry. Did you witness his recitals?

Oh yes, he would do them at the drop of a hat. Not many of them got written down because he forgot them as soon as he'd said them.

He was considered an entertainment factor in the local community. There was a certain amount of benevolence towards him. I don't know how many deep friends he made. I doubt if it was many. But he was on good terms with nearly everybody.

What would he have made of getting so much attention now?

Oh, he'd have revelled in it. He might have even been able to buy a suit.

Schwitters In Britain runs at Tate Britain from 30 January to 12 May. Interview by BBC News arts reporter Ian Youngs.

- Published18 January 2011