How positive thinking toppled Pinochet

- Published

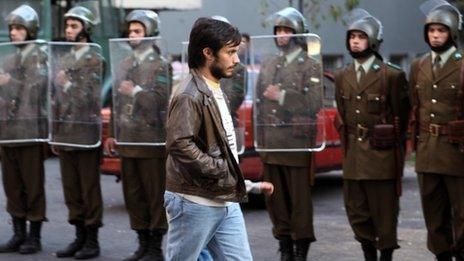

Gael Garcia Bernal's character Rene Saavedra takes on Pinochet's military dictatorship with a hope-soaked publicity campaign

Much has been documented on the rise and fall of Chile's brutal military dictator General Augusto Pinochet yet little on the men who brought about his demise. The Oscar-nominated foreign-language film, No, seeks to redress the balance.

The Spanish-speaking film, starring Mexican actor Gael Garcia Bernal, is set in Chile in 1988, when a public referendum was called on Pinochet's 15-year coup-seized leadership.

The people were to be asked to vote Yes for a continuation of Pinochet's rule or No for him to go.

While the Yes campaigners go down a hackneyed route of vaunting Pinochet's great leadership and trashing the opposition, the No camp realise a radical new approach is needed. The people are scared and sceptical of a corrupt process and will take some persuading to even go to the polls.

The answer is to hire advertising hotshot Rene Saavedra, who says they must harness the strategies of product advertising, namely the power of the positive message.

"Many people know how Pinochet got into power by overthrowing President Allende but very few know how he got out," says Bernal who plays Saavedra.

"Even I, who am from Latin America, didn't know about the campaign that went on. I didn't know how important publicity was to the movement and what actually went on.

"It was one of the most interesting things about the film and encouraged me to do it."

Unified front

Used to working on promotions for products such as fizzy drinks, Saavedra dismisses focusing on the atrocities of Pinochet's rule to take the sweet shop approach to the Nos' campaign: shiny imagery of rainbows and a beautiful future full of sun-soaked days of family fun.

"The film sees the birth of democracy in Chile through the eyes of a publicist," says Bernal.

"An archetypal publicist doesn't exist, but this character is fascinating because of his joyful attitude.

"He has a childish fascination with toys and things like his new microwave. These kind of things gave the character an interesting way to see the story."

The No camp, a group made up of 16 political parties, are unsurprisingly unconvinced. But they pull together behind Saavedra in a spirit of unity and camaraderie.

Eugenio Garcia plays a member of the Yes campaign in the film

It's a dynamic that followed through into the cast, many of whom are the real-life members of the No campaign.

"There was the fraternal aspect to making the movie, which got me closer to the drama and to the freedom that that moment in history experienced," says Bernal.

As for the members of the Yes campaign, they made a point of making themselves elusive.

"All the protagonists from the campaign were very up for making the movie. Some acted as themselves and others play their antagonists," says Bernal.

"They couldn't find people from the Yes campaign. There was only one person who was known but he didn't want to talk. A victory has many generals but a defeat has none."

One of the original No team is Eugenio Garcia, on whom Bernal's character is based. Garcia, a smiling and gentle man, says he was taken aback when approached by Chilean director Pablo Larrain.

"It was a surprise for me as this happened 25 years ago and then I forgot, did my job and got on with my life," says Garcia.

"Now when I see the movie, it's very emotional. It's a very good interpretation of how we all felt at the time, our fears and anticipation. It makes me remember all the emotions. It's beautiful."

Underhand tactics

Meeting Garcia was a true honour and also valuable to understanding and playing Saavedra, say Bernal.

It all adds to the film's air of authenticity, which Larrain has taken pains to achieve through the use of an old U-matic camera to help blend news footage from the era with the acting scenes.

Rene Saavedra (Gael Garcia Bernal) is deep down just an ordinary family man

At heart, Saavedra is just a simple man of the people, deeply concerned for the young son who lives with him and longing to be reconciled with his estranged wife.

When the Yes campaign hit back with underhand tactics, Saavedra feels the threats on a deeply personal level, rather than as part and parcel of the dirty game of politics.

It sums up the other feeling pervading No: intimacy.

This, Bernal explains, is down to Larrain. No is the final part in Larrain's trilogy covering the Pinochet era. The first two films were Tony Manero and Post Mortem.

No signals a closure for the director, who was a child at the time of the events of the film and whose parents were Yes voters.

"It's a film that is very personal to Pablo. He was 12 when this happened," says Bernal. "It is, for him and other Chileans, a reconciliation, not just with society or the country, but with one's own history."

Ultimately, the No campaign is triumphant. An unexpected 97% of registered voters turn out at the polls. The No campaign wins almost 56% of the vote.

Pinochet stepped down in 1990 after losing democratic presidential and parliamentary elections. When he died in 2006, he was still to stand trial for human rights abuses, as ordered by the Chilean courts.

This "injustice" is just one of the many issues that make No relevant to today's audience, says the politically-minded Bernal. But would he ever turn his interest into a career?

"I am very interested in politics," says the actor, who is a big supporter of human rights group Amnesty International.

"But as for going into it seriously in a formal way, I can't see that happening. Then again how many politicians have said the same?"

No is released in the UK on Friday, 8 February.

The Academy Awards are on Sunday, 24 February.

- Published10 September 2012

- Published8 June 2012