Jonathan Miller complains of ageism in the arts

- Published

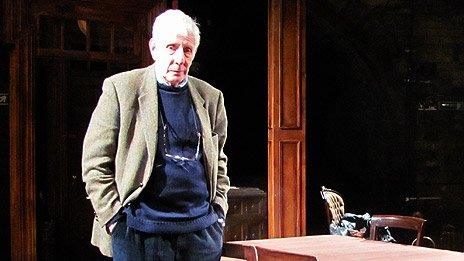

Jonathan Miller, pictured on the set of his latest production

Jonathan Miller's plays, operas and TV programmes have made him a grandee of British culture. Now 78, he says ageism has crippled his career and that he was "silly" to accept a knighthood.

"When you get to my age, there's a certain point at which you're assumed to be dead," says Jonathan Miller, explaining why there has been a five-year gap between plays he has directed.

"Or if not dead, then almost certainly rotting. So they don't ask you at all."

Miller, who was knighted in 2002 but who prefers not to be be called Sir Jonathan, may be advancing in age. But his formidable intellect and indignation are obviously undimmed.

He is sitting in a cafe in Halifax at the home of the Northern Broadsides theatre company, for whom he is currently directing the 1912 play Rutherford and Son.

Although he has continued to contribute to revivals of his famous opera productions, some of which have been going strong around the world for three decades, his last play was Hamlet, at the Tobacco Factory in Bristol, in 2008.

Miller (right) starred in Beyond the Fringe with (l-r) Alan Bennett, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore

After Rutherford and Son, he has a "very modest" opera lined up in Devon in the summer but no other offers of work.

"Unless you spend a great deal of time networking and going out and having dinners and making appointments and seeing people and schmoozing, you don't get jobs after a certain age," he says.

"Next year I'll be 80, and they assume that if you're 80, the chances are that you're either in a care home, and that in any case you're probably dead from the neck up, so you don't get jobs.

"But if you keep your wits about you and you don't develop Alzheimer's, you're probably better the older you are because you've seen a longer stretch of human life.

"I think I'm probably as good if not better than I was when I was younger. But they ignore that entirely."

He is grateful, then, that "they" did not include Barrie Rutter, the acting and directing powerhouse behind Northern Broadsides, whom Miller first met while directing for the Royal Shakespeare Company in the 1980s.

Rutter sent Miller the script for Rutherford and Son, a long-neglected tale of family feuding by Githa Sowerby, and the director accepted at once.

"It's an extraordinary play," Miller says. "It was written only eight or nine years after The Cherry Orchard, and I think it's every bit as good as Chekhov."

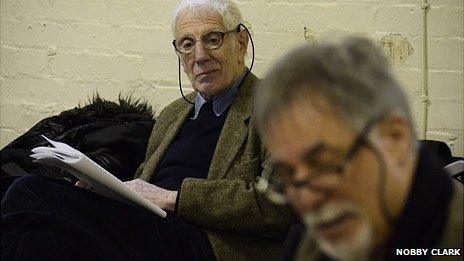

Miller is directing Barrie Rutter (front) in Rutherford and Son

Before Halifax and Bristol, Miller's most recent theatre production was The Cherry Orchard at the Sheffield Crucible in 2007.

He has not avoided working in London, but "deeply disapproves" of the idea that everything of importance happens in the capital.

"And I really disapprove of the idea of the thing called the National Theatre being on the south bank of the Thames," he says.

"It's as absurd as having the National Health Service at St Thomas' Hospital [also on the South Bank].

"I think there's a whole group of theatres all over the UK which at a certain level ought to have that NT logo, in that they are, as this is, a national theatre."

Miller was an associate director at the National Theatre under Lord Olivier, but fell out with his successor, Sir Peter Hall, in the 1970s.

Yet he did persuade the current incumbent, Sir Nicholas Hytner, to stage his production of The Matthew Passion in 2011.

In attempting to sum up Miller's career, it would probably be quicker to list what he has not done than what he has.

He was on course to become a neurologist when his satirical university revue Beyond The Fringe, co-written with and co-starring Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett, became a 1960s sensation.

He then turned to stage directing, then editing and presenting television documentaries on the arts and sciences, as well as directing films and writing books.

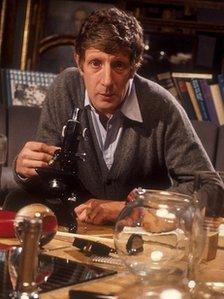

Miller presented the landmark science series The Body In Question

He directed his first opera in 1974, despite being unable to read music and claiming never to have even seen one. Yet he seemed to manage to make a success of whatever he tried.

Critics have not always liked his creations, however, and he has gained a reputation as something of a pompous curmudgeon.

That may be a by-product of his straight-talking nature and his supreme confidence, which mean he sees no need to pull punches or partake in false modesty.

With confidence is also openness, curiosity, an attraction to absurdity, a disdain for authority and a seemingly complete grasp of language and whatever subject he chooses to discuss. Who's Who lists his only recreation as "deep sleep".

He was knighted in 2002 but now asks that he is not addressed as Sir Jonathan. "I shrivel as soon as I hear anyone doing that," he says.

"I have serious misgivings about having accepted it. It's part of the general hemisphere of English snobberies in which titles are said to be so important.

"It goes with people who can boast about having been at Eton or having been in the Royal Horse Artillery.

"I was silly to have accepted," he continues. "My children urged me in the end. They said, 'Go on, Dad, you deserve it.'

"My wife was furious when I accepted it and cannot bear to be called Lady Miller."

Miller's other TV work included directing a 1980 BBC production of Antony and Cleopatra

At the end of an Arena documentary about his career that was broadcast last year, Patrick Uden, the producer of some of Miller's television documentaries, suggested Miller was unhappy with the way the world had treated him.

"I don't think the world has treated me badly at all," Miller responds. "I sometimes get reviewed occasionally spitefully by critics.

"But I don't think the world has treated me badly. I've been rather well treated I think. I've done a lot of work which I've enjoyed doing.

"Ageism has treated me badly. But it's also treated lots of other people badly as well. People assume that you ought to be cheerful all the way and I've got this, I think, unjustified reputation for being grumpy.

"I'm angry or disappointed at the condescension which I encounter from people who are 30 years younger than I am and know 100 per cent less than I do. That's all."

Rutherford and Son is at the Viaduct Theatre in Halifax until 16 February, when it begins a UK tour.

- Published7 March 2012