Consider this: How film-makers court the Oscar voters

- Published

Billboard posters become part of the Los Angeles landscape in the fight for Academy votes

The Oscar ballot closes on Tuesday, marking the calm after the storm, as the protracted and fevered period of awards season film promotion comes to an end. It's all designed to grab the attention of the 6,000 Academy voter members, secure a nomination and hopefully a win. But is such exertion really worth it?

Commonly known as campaigning, this frenzy has become a multi-faceted business.

Many of us are familiar with the giant billboard posters plastered around Los Angeles during awards season, which takes in the Golden Globes, the various guild awards and the Oscars.

These posters often feature the words "For your consideration" and push for nominations in certain categories; screeners of films sent to Academy members are equally well-known.

But campaigning now goes further, taking in parties, Q&A sessions, promotional websites, quirky gifts, special appearances and more.

From the outsider's perspective, it all seems rather hysterical but, says Oscar nominee Peter Lord of Aardman Animations, the possible benefits of an Oscar nomination alone justify such behaviour.

"The amount of contacts and negotiations I've had just for this nomination has been prodigious," says Lord, director of best animated film nominee The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists!

Publicists remain tight-lipped on the cost of their Oscar ad campaigns but Screen International's Nigel Daly, says the average spend by a bigger US studio is around $250,000 (£161,000) - $300,000 (£193,000).

"But there is no ceiling and some will spend $500,000 (£322,000). The years of the big money have gone though, it's very measured," says Daly.

"They watch the reviews and various other awards results and they can tweak accordingly. Much is spent online now too, which allows for measurement and targeting."

Building momentum

To economise, "trophy" films - those studios consider Oscar contenders - are typically released at the end of the year.

"There is a deliberate design to bring out good films late on, the summer is almost uniquely confined to huge special effects comic book films. It's always been the case, but now more than ever," says Glenn Whipp of the LA Times.

The advantage of this is that campaigning can tie in to normal promotion, cutting costs and building momentum over a long period, up to the final ballot.

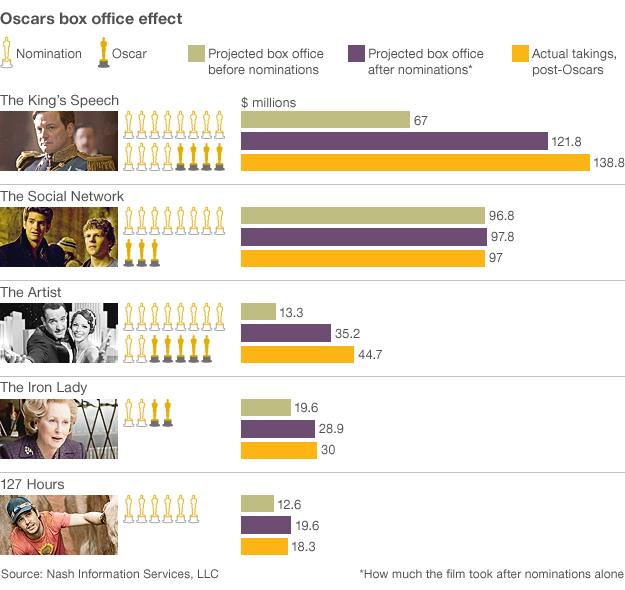

Box office analysis shows that nominations have more of an impact on takings than winning an Oscar

An example this year was Argo. It opened in the US in October but effectively began its campaign at the end of August with a big premiere at the Telluride festival, says Whipp.

It went on to Toronto and other big festivals and has not stopped, even though a normal promotion period - in the US and overseas combined - would end after a couple of months.

Yet, the extra spend and effort is not just about massaging star egos. Studios also have their coffers firmly in mind.

Nominations and awards can translate into box office gold. Unsurprisingly perhaps, the more accolades a film picks up along the way to the Oscars, the more people want to see it.

Data from Nash Information Services in California shows 2011's big Oscar winner, The King's Speech, saw its predicted box office takings rise by $54,790,849 (£35m) after nominations and its final takings, after winning best picture, by $17,017,401 (£11m).

Conversely, in 2011, The Social Network saw a slight box office bump after receiving 11 nominations but, when it failed to pick up any major Oscar awards, its earnings fell short of predictions by $806,210 (£519,222).

Harvey Weinstein (right) is this year banking on Silver Linings Playbook and its star Bradley Cooper (left)

DVD rentals also feel the Oscar effect. After the 2011 ceremony, pre-orders for The King's Speech from Lovefilm were up 281% and other Colin Firth titles also saw renewed interest, including 2005's football movie Fever Pitch, which saw a 340% rise in rentals.

The King's Speech was a triumph for Hollywood's king distributor and promoter Harvey Weinstein.

He insists that the best way to push a good film is to get bums on seats. His films open in a few cinemas and then expand once nominated. This was the case with The King's Speech and 2012's triumph The Artist, and again this year with Silver Linings Playbook.

"We said, 'We're going to roll the dice and the take chance it will be critically well-received and get an award accolade that would keep it in the ether and, through word of mouth, more people would go to see it,'" says its star Bradley Cooper.

However Weinstein has also been known to use more artful methods. Ahead of nominations for the 2012 Oscars, he turned up at a screening for silent movie The Artist with two of Charlie Chaplin's granddaughters, keeping its profile high amongst the Hollywood cognoscenti who decide the victors.

Academy whim

The Academy - no doubt fearful of potential damage to its well-guarded image - last year tightened campaigning rules. Limiting the number of post-nominations screenings and outlawing hospitality are just two examples of stricter control.

But there is an argument that some winners are born, not made. Academy voters take notice of what the various critics groups find worthy but they also have their own particular tastes.

Amour's star Emmanuelle Riva gave it the pedigree to make it a best picture nominee

Films such as Lincoln that tackle weighty issues and tap into patriotism are favoured, says Wendy Mitchell, editor of Screen International.

"Lincoln's strength is predicated on the story and its bi-partisan effort to pass the Third Amendment which, from talking to some voting members and the public, makes them feel very proud of the democratic process at a time when Congress is in gridlock and it's very hard to pass laws."

Foreign-language movies are a hard sell and are rarely chosen for best picture, instead sidelined to their own category.

"Getting audiences to see foreign-language films is tough. There was an era when any good art film was a big event but now things have changed and it's all down to smart marketing," says Mitchell.

And smart marketing by distributor Sony Classics has played a big part in securing multiple nominations, including best picture, for French-language film Amour.

Sony would have played on the fact that Amour had won at Cannes, had a well-respected director in Michael Haneke and a revered leading lady in Emmanuelle Riva, says Mitchell.

As for feature-length animations, they could be seen as underdogs too. Without their own category they might never be seen, let alone receive awards, says Peter Lord.

"The Oscars are obsessed with actors and celebrity and we don't have ours on screen. Pixar is a powerful company making heartfelt films and want them to be considered for best picture," says Lord.

Conscientious objectors

Joaquin Phoenix is among a handful of stars who stay adamantly aloof

And then, against this backdrop of aggressive promotion, there are those individuals who really do seem to prove it's all a waste of time.

Joaquin Phoenix refused to take part in any campaigning for The Master, as did Sean Penn for the film Milk.

But Phoenix is a nominee going into this year's ceremony, and Penn went on to win best actor at the 2009 Academy Awards.

"These are actors who believe the craft should speak for itself. They don't like publicity, they are private people," says Whipp.

It's a sentiment Lord agrees with.

"You want to believe, as a film lover and an optimist, that the best film will win. With any vote or election, to think a vote has been bought is distasteful," he says.

"Lobbying, campaigning is not my instinct but then that's probably a very British thing to say. I believe in the old-fashioned way: Virtue will triumph."