David Bowie: Appreciating the eclecticism of an enduring star

- Published

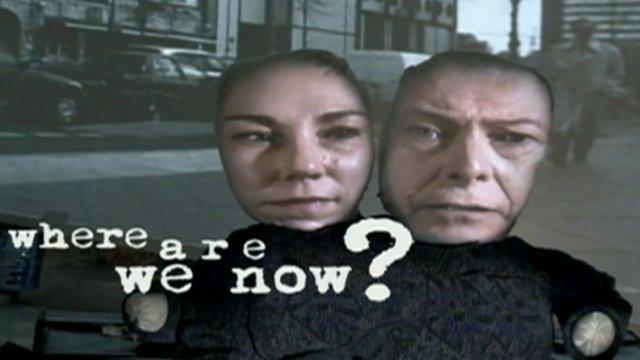

Bowie's latest album came as a surprise to fans

David Bowie enthusiast Paul Maguire gives an appreciation of David Bowie's work past and present as the singer releases his first album in 10 years.

The Next Day has dawned. Neither retired nor dying, we have new Bowie. Somebody up there likes us.

It was after years of silence that Where Are We Now? sneaked out earlier this year to widespread acclaim. But it merely took a mention of a Cold War era Potsdamer Platz to mean martial law was imposed on all reviews.

Immediately it was decreed that comparisons to Bowie's Berlin Trilogy must be made in knowing, reverential tones. It's as if that part of his back catalogue has its own Berlin Wall built around it.

Low, Heroes and Lodger together cast long, dark shadows over other treasures with less convenient catch-all labels. Not least the trilogy's immediate predecessors in the Bowie canon.

Released between the Ziggy and Berlin eras, Diamond Dogs, Young Americans and Station To Station form a musical troika which sashays through dystopia, dancing, drugs, Orwell, Lennon and Aleister Crowley. But tales of alleged Nazi salutes at Victoria station, exorcisms, and a daily diet solely consisting of milk, peppers and cocaine always dominate any discussion of these records.

1974's Diamond Dogs is easy to get into. You just have to love the idea of glam rock made by someone who has read 1984 once too often and is convinced our society is doomed. Which was something in mid-70s Britain that wasn't hard to envisage.

It also helps to not be disturbed by the images of a hybrid canine rock star with airbrushed genitals as portrayed on its cover. This is Bowie's most DIY album. He plays most of the instruments himself. Scratchy guitars, weirdly beautiful Moogs and Mellotrons abound.

It features his greatest ever vocal performance on the Sweet Thing medley. With Rebel Rebel you get both his best riff and exactly the record you'd have wanted to hear on a tinny transistor radio as the Thought Police came to take you away.

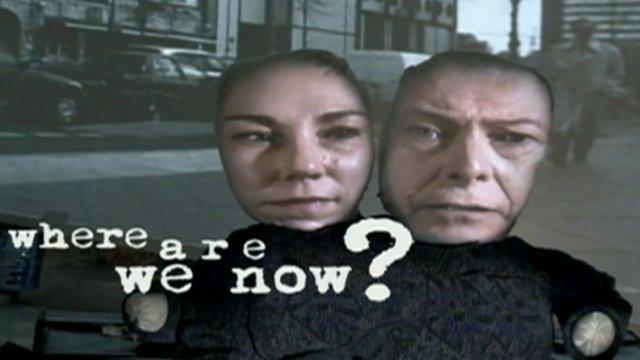

Bowie has only rarely played live in the past 10 years

Meanwhile, the jagged wah-wah guitars on 1984 conjure up visions of Winston Smith meeting John Shaft in a post-apocalyptic working men's club somewhere on the Isle of Dogs.

Young Americans followed in 1975. David Sanborn was Bowie's main musical foil which means his saxophone playing dominates this excursion into what Bowie called "plastic soul".

This may be because it sounds like it was recorded inside a plastic bag. It's airless and constricted. Soul albums don't sound like this.

It was recorded at the Sigma Sound studios in Philadelphia, the title track and John Lennon collaboration Fame were its hits and have been the staples of Greatest Hits ever since.

But just listen to them. You can dance to them but they just sound odd. Philly Soul? Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes didn't sound like this. Try the ballads such as Win and Can You Hear Me? or the up-tempo grooves of Fascination and Right.

The music is on the one hand his most accessible yet, but it makes you nervous. It doesn't sound like David Bowie, but then it doesn't sound like it could be anyone else. Better still, it contains arguably one of the world's worst Beatles covers in the shape of a second duet with Lennon on Across The Universe.

To promote the album he didn't tour but instead engaged in an epic skeletal duet with Cher on her TV show. Search for it on YouTube, it's unhinged.

Station To Station was then released in early 1976. This is the peak moment in Bowie's back catalogue. The album was made shortly after he had filmed his starring role as the alien Thomas Jerome Newton in Nicolas Roeg's The Man Who Fell To Earth.

He took the visual elements of that character and turned it into his final all-encompassing persona, that of The Thin White Duke.

Under this guise he decided to record this next album in Los Angeles. Whatever Bowie was reading and imbibing during his sojourn in LA the effect was not healthy.

Bowie reinvented himself with different personas

His concert tours had the air of a Nuremburg rally, reminiscent of Hitler acolyte Albert Speer's Cathedrals of Light. That's an artistic homage that one might not want to encourage.

That aside, the six songs contained within the album are all masterpieces. The title track is a 10 minute tour de force.

Phased locomotive sound effects combine with niggling distorted guitars to conjure up a nightmare journey across a shuttered, locked-down totalitarian state. Halfway through the mood breaks and the tension dissipates.

But Bowie's assertion that "it's not the side effects of the cocaine..." is fooling no-one. It certainly sounds like it's just that.

Golden Years, the album's hit single slithers and slinks its way out of your speakers. The story has always circulated that the song was offered to Elvis to cover, the mind somersaults with glee at the image of him doing it in his final Vegas years.

TVC15 is a piano led romp through tales of a TV set eating your girlfriend. Surely that happens to us all? With the track Stay Bowie invents a form of glacial European flavoured funk that points directly to his future direction.

That direction was towards Berlin and the entrance into a new phase of his record making. A phase that sees him cast off character lead public personas and traditional pop song structural norms.

There is no denying Low, Heroes and Lodger are great records. In hindsight who wouldn't want to have recorded next to the Berlin Wall, shared a flat with Iggy Pop (surely one hell of a washing up rota) and popped out to transvestite cabaret clubs of an evening?

But, when lauding his new work in the same old frames of reference we should do David Bowie a further service. He barely recalls making albums such as Station To Station. We should remember for him.

- Published11 January 2016

- Published8 January 2013

- Published8 January 2013