Napster: From bedroom to silver screen

- Published

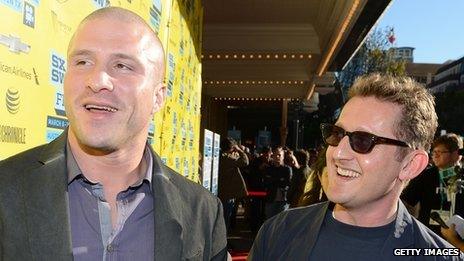

Napster founder Shawn Fanning (l) and director Alex Winter premiered their film, Downloaded, at the 2013 SXSW Music

To some, they were pioneers of a revolution. To others, the owners of music file-sharing service Napster were no better than online terrorists, hijacking one of the biggest industries in the world by offering music to fans for free.

Now the story of Napster, told from both sides of the debate, has been made into a documentary by director Alex Winter - famous for being one half of movie duo, Bill and Ted.

The film, called Downloaded, had its world premiere at the SXSW music and film festival in Texas this week.

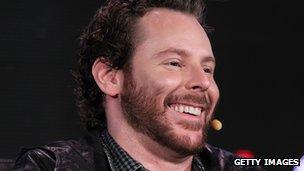

It was attended by the entrepreneurs who started Napster - 34-year-old Sean Parker, who went on to co-finance the brands Facebook and Spotify, and 32-year-old Shawn Fanning from Massachusetts, who is also a Silicon Valley investor.

The film documents how the pair became friends as teenagers in an internet chatroom, and discovered a shared love of music, as well as a talent for emerging online technology.

"We were just kids at the time," Fanning says. "Back in 1998, when we first moved to California to start this company up, we were 17 or 18 years old. Neither Parker nor myself went into it seeking this huge fight with the music industry, let alone re-architect it."

"The pair of us had never left our hometowns, or even been on an aeroplane before," Parker says. "We founded Napster as music fans. It was hard that at one point, all these artists we idolised seemed to want to kill us."

Drummer Lars Ulrich (l) of Metallica testified against Napster in 2000 for copyright infringement

Although director Alex Winter first met Parker and Fanning 10 years ago, he says he only started making the documentary recently.

"I realised that the conversation we were having 10 years ago about Napster, about whether they were hijackers and thieves, hadn't actually changed at all in the wider context of the internet.

"When you look at something like Wikileaks, there is still a great deal of suspicion and debate about the sharing of information online. Napster was there right at the start of the argument about transparency and freedom."

In 1999, Napster was one of the first online communities created by the still fledgling internet. Its technology allowed fans to share and swap music files on MP3 formats - for free.

It proved popular; at its height in 2001, Napster had 26 million users, changing not only the way fans bought their music - from a physical CD to downloading - but also their perception as to whether they had to pay for it.

However, record labels didn't share the audience enthusiasm, and accused Parker and Fanning of being "pirates" who wanted to bring down the industry. Parker disagrees.

"Fifteen years ago, the music business was a shining example of US success abroad. It embodied ideals of America and was worth about $48bn (£32bn) to the economy.

"We were teenagers who barely knew what we were doing, and we were up against not only the labels, but their media machine. They demonised us. We didn't set out to create music piracy, we wanted to create a service that filled a void, and frankly, it was a void because the labels were incompetent.

Sean Parker told disbelieving journalists in 1999 that music would be listened to on mobile phones

"In 1998, there was the technology available to have created a Spotify or an iTunes service back then. The labels never did it. Their entire focus at the start of the digital age was, 'how do we lock this up, how do we make sure that not even a single piece of content is ever stolen from us?' They were too caught up in their fear of piracy, and because they were unable to take the lead, they lost the entire industry and have been playing catch-up ever since."

Some artists embraced Napster and claimed it ultimately boosted sales; in 2000 tracks from Radiohead's Kid A album were leaked on the site before its official release.

The band had never had a Top 20 album in the United States, but in the wake of the publicity it went to number one in the Billboard charts. Other acts, though, and several record labels, sued the company for copyright infringement - most notably, heavy metal band Metallica and rapper Dr Dre.

After losing in the US Court of Appeal in 2001, Napster had to shut down in July of that year. It went bankrupt in 2002, although parts of the company were sold off and would eventually become an online music store.

In two years of operation, though, Parker claims that the company presided over "a golden age of music" which he is still hoping to replicate.

"Back in 1999, I have never seen so much passion and so much excitement about music from fans, about what the new technology enabled them to do. I haven't seen it before or since."

Several other websites continued to offer file-sharing services, and although Napster was closed, there was no shutting the door on the idea that music could exist outside of a record label's protection - an effect, Alex Winter says, "you still see at a festival like SXSW to this day".

"Here you have around 2,000 bands playing gigs, many of whom don't have a label, offering much of their music directly to their fans via a website, and some of that will be for free. A free taste of a band's content is now a standard promotional tool. Napster's legacy is how the entire music industry operates today."

The archive footage of Downloaded shows a teenage Parker telling journalists that in the future, fans will listen to music on their mobile phones.

Justin Timberlake starred as Sean Parker in the film, The Social Network, alongside Andrew Garfield and Jesse Eisenberg (L-R)

"Telling anyone that," Parker remembers now, "was like trying to sell someone a light bulb before electricity was invented. I always had this idea that one day we'd listen to music on all sorts of different devices, and that consumers would pay for the convenience of having one music collection available across all their different platforms. I said that back in 1999, but no-one was ready to hear it."

Last year, Parker's personal wealth was estimated at around $2bn (£1.3bn), mainly due to his part in founding Facebook. He also went on to invest in music streaming service Spotify, which offers a subscription service to users. Shawn Fanning is also a millionaire - but he says Napster was not formed for the money.

"We didn't make much cash out of Napster at all, the lawyers were the real winners out of the entire experience. We were kids who went to California, saw some crazy stuff, learned a lot about people and business and it was an incredible ride. I wish the entire thing had been handled differently on both sides, though."

"We thought we were starting a company, but actually it was a cultural revolution," Parker says, "although you never realise you are in the middle of one at the time. You don't get many opportunities in life like that. However, I feel like my part in the evolution of the music industry is now over. I'm done now."

- Published16 January 2013

- Published6 December 2012