The business of David Bowie

- Published

Will Gompertz reported on David Bowie's influence, in 2013

Andy Warhol once famously said "good business is the best art".

At the time it sounded fey and facetious, but as was often the way with him, it turned out to be smart and prophetic.

He was outing a vulgar truth from the closet, which is that most artists like to make money, and the way they do it is by making art - it is their product, it is a commodity.

As we know, Warhol's ideas caught on - and not just in the art world.

They inspired a 16 year old called David Jones from Bromley: a young man fed up with his job in advertising who had a yearning for fame. What, he thought, if I turned myself into a product? What if I became a commodity and the fans my consumers?

After a couple of false starts, he launched his first brand called…David Bowie.

Some time later, in a BBC interview, he rationalised what had been instinctive: "I thought, well here I am. I'm a bit sort of mixed up creatively.

"I've got all sorts of things going on, that I'm doing on stage or whatever. I'm not quite sure if I'm a mime or a songwriter or a singer - or do I want to go back to painting again. Why am I doing these things anyway? And I realised it was because I wanted to be well known, basically.

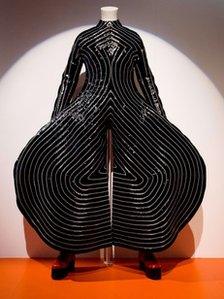

A collection of Bowie's costumes are part of the forthcoming retrospective at the V&A

"And that I wanted to be thought of as someone who was very much a trendy person, rather than a trend. I didn't want to be a trend, I wanted to be the instigator of new ideas. I wanted to turn people on to new ideas and new perspectives. And so I had to govern everything around that.

"So I pulled myself in, and decided to use the easiest medium to start off with - which was rock and roll - and to add bits and pieces to it over the years, so that by the end of it, I was my own medium. That's why I do it, to become a medium."

David Bowie is the Steve Jobs of rock, the Picasso of pop. He synthesises influences past and present, drops them into the Bowie Blender, and serves up something fresh and exciting. Jobs would come up with a new product, Picasso a new style; Bowie launches a new persona.

Take Ziggy Stardust for example. In his DNA you'll find Japanese Kabuki theatre, British rock and roll, and late 1960s dystopian sci-fi. Bowie turned pop art into post modernism, where superficiality and altered images were designed to question the certainty of past generations.

Here was a product wanted by British youth and by Young Americans. A pink-haired, cat-suit-wearing, androgynous-looking style leader - a new hero who dared a generation to be different. Or as those Apple ads would a quarter of a century later say, to think different.

While the Rolling Stones and Dylan were defined by their music and therefore to a certain extent trapped, Bowie was defined more as a character actor - a vaudevillian performer, which meant he was free to ring the ch…ch…changes whenever he wanted.

Here's what Bowie said about that in another BBC interview: "One painting isn't the painter's life. And often a painter will do a lot of paintings and he's only satisfied with a couple in his entire career, and that applies to me definitely.

"I'm only happy with a couple of albums. Occasionally I'll strike on something that's very good. But you can't set out and do a painting and say 'this is it', but it is it. You just hope and try and if it doesn't work, you put it to one side and try another one."

To paraphrase his mentor, Andy Warhol, Bowie's best art has been good for business. For an avant-garde artist his estimated fortune of £100m is impressive, especially as he has stepped off the lucrative touring circuit for most of this century. But it could have been a lot more.

His early publishing agreements and tour arrangements were not the sophisticated financial deals made by someone with a Harvard MBA, but with an A-level in art from a tech college in South London.

And his venture into the world of high finance in the mid-1990s is considered by some to have been part of the 'securitisation' craze that led to today's global financial crisis.

The infamous Bowie Bonds of 1997 saw the worlds of rock and stock merge in a deal in which bonds were issued against Bowie's future income.

But for once the musician's grasp of the zeitgeist had momentarily loosened, and he failed see the negative impact digital downloads was going to have on music sales.

Author Paul Trynka, who wrote the Bowie biography Starman, thinks he knows what led to this loss of trend-spotting form.

"When he got to the point where he realised he didn't own his own music, I believe that inspired a full-blown mental breakdown," he says.

"Everyone talks about his cocaine period - that came at the same time that he realised that his manager, Tony Defries, owned all of his music. Here's a guy who'd made all these massive sacrifices to make music, and he doesn't own it all.

"That really bothered him. He didn't talk about it - and in a way, that in itself is significant. The desire to control his music is what led to the creation of Bowie bonds.

"Ultimately, those bonds were classed as junk. It's something that didn't seem to benefit many artists in the long run - and there are some people who speculated that the notion of issuing bonds kicked off the crash of 2008. So they worked for him, but not for many other people."

What has worked is David Bowie's comeback album The Next Day. Without subjecting himself to any interviews, or taking on an exhausting tour, it has garnered praise, headlines and now a number one spot in the charts - the first time Bowie has enjoyed pole position for 20 years.

And with it comes the launch of a new image; that of a nostalgic legendary rock star called David Bowie. It's a brand he has reinforced by making his own back catalogue the album's subject.

Hence, perhaps, the no interviews policy and a career retrospective at the V&A in which he did not participate: this new persona wants us all to focus on his past, not his present.

Clever stuff. Worthy of Andy Warhol himself.