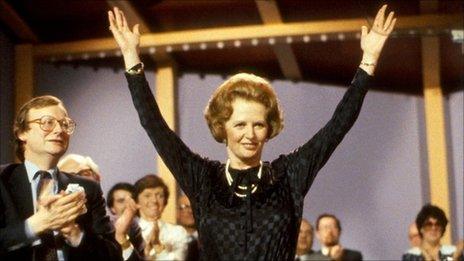

Margaret Thatcher: An inspiration to artists?

- Published

Has any other post-war politician provoked so much artistic output?

The best scene in The Iron Lady is the one that opens the movie.

We see an elderly and confused Baroness Thatcher in an inner-city supermarket, circa 2011. She is buying a carton of milk. As she walks toward the counter, a brash, middle-aged businessman rudely cuts in front of her. He is on the phone, haggling over a deal, oblivious to his surroundings. As he leaves and she takes her place at the counter, a young man in a rush queues behind her.

He stands a little too close, fidgeting impatiently, earphones in, music blaring. The day's newspaper headlines report: TERROR IN HOTEL BLAST. The message is clear. The once indomitable "Margaret Thatcher the milk snatcher" is now frail and bewildered by callous contemporary Britain: a culture she had a large hand in creating.

The irony is lost on the old lady portrayed by Meryl Streep, but not on the viewer. Thatcher's political children have not turned out as she thought they would, but to her bafflement, society has: There is no longer such a thing.

The scene is a subtle version of the artistic community's typical comment on Margaret Thatcher's legacy. From Ben Elton and Alexei Sayle to Jeremy Deller and Ken Loach, the prevailing view from the arts is that the first female British prime minister was not a good thing.

"You privatise away what is ours," sang Billy Bragg in the aptly-titled Thatcherites. "We'll take it back one day, mark my words, mark my words."

Margaret Thatcher chose her Desert Island Discs while leader of the opposition in 1978

Perhaps her one and only redeeming feature was that she acted as a catalyst for creativity. As Gerald Scarfe, who famously lampooned Thatcher with his scathing caricatures, said: "I didn't agree with her values, but she was amazing material. I could turn her into anything acerbic or cutting, like a dagger or a knife, probing and vicious."

Has any other post-war politician provoked so much artistic output? Margaret Thatcher has been the subject of theatre, film and television productions, of books and poems, paintings and performances.

For the 1980s alternative comedy movement she was both the inspiration and butt of its jokes. And for many a post-modern political pop song she was the go-to figure.

The iconoclastic "living sculptures" Gilbert and George are the only artists I can recall that have openly come out as Margaret Thatcher fans. They once told the Daily Telegraph: "We admire Margaret Thatcher greatly. She did a lot for art. Socialism wants everyone to be equal. We want to be different."

It's a comment that reveals another of the ex-prime minster's ironic legacies: in the arts world it is now radical to be Conservative.

"She did a lot for art," said George Passmore (left) of Gilbert and George

To many, her attitude towards the arts was encapsulated in the notorious Saatchi & Saatchi ad campaign for the V&A, which carried the infamous tag line "An Ace Caff with Quite A Nice Museum Attached". This was Thatcherism applied to high culture. Market economics over intellectual curiosity, consumption over contemplation.

But there is a counter argument, an argument that says Margaret Thatcher was the instigator of Britain's recent artistic golden age of flourishing museums, packed playhouses and general creative confidence.

At the very least it could be argued that, by deregulating the markets. she helped turn London into the world's capital city, which has brought new money, ideas and peoples to the country. The once shabby capital became the place to be.

And then there is the man whose company was behind that V&A ad, Mr Charles Saatchi. When he opened up his eponymous Boundary Road gallery in north London he started a process that would lead to the UK becoming one of the most exciting, innovative and open places in the world for an artist to live and work.

Damien Hirst told me that it was Saatchi's gallery that jolted him into action. As a student, he had no interest in making work to be shown at The Tate. But when he went up to Boundary Road an exciting future became apparent. "I wanted to make pieces that would go in there," he said.

Margaret Thatcher might have dismissed Francis Bacon, Hirst's hero, as "that man who paints those dreadful pictures", but the YBA artist admits that part of his success is due to the enterprising culture she created.

Damien Hirst's pickled shark, on display at the Saatchi Gallery, both arguably indebted to Margaret Thatcher

And it was Michael Heseltine, a member of the Thatcher cabinet, who suggested to the prime minister after the 1981 Toxteth riots in Liverpool that the city needed investment, and not to be put into a state of "managed decline" as suggested by the then-Chancellor Geoffrey Howe.

Heseltine said that he had "no difficulties at all in persuading the prime minister to let me do what I wanted to do." And his plan included encouraging the Tate Gallery to create a north-western outpost, as part of his larger rejuvenation plan for Liverpool's Albert Docks.

A few years later the new Tate Liverpool, housed in an old industrial building, set about showing what art could do to help regenerate an area. It's a formula that has since been copied across the country, and one which created the blueprint for Tate Modern.

If Margaret Thatcher had backed her chancellor and not her secretary of state for the environment, the cultural landscape of the UK might look much bleaker.

But it was backing another chancellor that was perhaps her greatest contribution to the arts.

She gave John Major his big political break with a job in the cabinet and then supported his campaign to be prime minster. Once in post, Major created the National Lottery and its charitable framework, which included a commitment to spend money on the arts. Cue the so-called Golden Age.

The standard position on Margaret Thatcher's appreciation for the arts is that she didn't have any. But that is patronising. Listen to her 1978 Desert Island Discs interview and it is clear that she liked and participated in the arts. She played the piano, sang in the Bach Choir when at Oxford, and was knowledgeable about opera.

True, her tastes were classical and conservative and she found contemporary culture baffling, but then so did many in her generation - several of whom had run or sat on the boards of arts organisations.

Margaret Thatcher will always be a divisive figure. She oversaw some good, some bad, and some very ugly times. She certainly wasn't a champion of the arts but, whether she meant to or not, she probably did contribute more than she is credited for, albeit acting quite often as the grit in the oyster.

- Published9 April 2013

- Published8 April 2013

- Published8 April 2013

- Published9 April 2013