Dan Brown on 'hurtful' reviews and saving the world

- Published

Before Inferno, Brown's five novels had sold 190 million copies

The latest thriller from The Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown is expected to be the best-selling book of the year. But that has not stopped literary critics from gleefully tearing Inferno apart.

Brown discusses his "hurtful" reviews, taking inspiration from Dante and why he thinks readers should worry about the novel's central theme of global overpopulation.

"Bilge", "noxious malarkey" and "entertaining twaddle" are just some of the choice phrases that have been picked to describe Dan Brown's Inferno in the press.

It is no surprise that Inferno has been met with such a reception. Since The Da Vinci Code was published a decade ago, Brown has been the author that the literati love to hate.

But nor is it a surprise that Inferno immediately shot to the top of best-seller lists, had the highest number of pre-orders since JK Rowling's The Casual Vacancy and is odds-on favourite to be 2013's biggest-selling book.

Brown's enthralling yarns, which intertwine plausible-sounding conspiracy theories with life-or-death treasure hunts and the resonating weight of art history, are incredibly popular. Before Inferno, Brown's five novels had sold 190 million copies.

Of anywhere in the world, he says his books get the worst reviews in the UK, where it "seems to be sport to kick me around a bit".

Does the criticism hurt?

Inferno was surrounded by strict secrecy before its publication last week

"I wish everybody loved what I do, of course," he replies. "Of course it's hurtful. I've learned that universal acceptance and appreciation is just an unrealistic goal.

"If a reviewer is beating me up, I just say, 'Oh well, my writing is not to his or her taste.' And that's as far as it goes. Because I will simultaneously read a review where somebody says, 'Oh my God, I had so much fun reading this book and I learned so much.'

"I learned early on not to listen to either critique - the people who love you or the people who don't like you.

"If you believe the people who love you, you get lazy. And if you believe the people who hate you, you become... maybe intimidated, or whatever the word might be, and you don't write as well.

"The best thing to do is just put on the blinders, write the book that you would want to read and hope that other people share your taste. It's really that simple."

In Inferno, Brown reintroduces Harvard symbology professor Robert Langdon, who wakes up with amnesia in Florence, Italy, and has to try to save the world from an evil scientific genius while simultaneously evading a crack squad of assassins.

Dan Brown: "It is a terrifying landscape that Dante paints"

Langdon must follow clues related to 14th Century Italian poet Dante and his epic creation Divine Comedy. Dante's gruesome vision of hell as depicted in the opening part of the poem, Inferno, may be where humankind is heading if Langdon fails.

"I was researching The Da Vinci Code. I had become very entrenched in church philosophy and came to understand that Dante's Inferno really inspired and informed our modern Christian vision of hell," Brown explains.

"This thing that we consider to be so important to Christianity, this idea of hell, didn't really come from the Bible. It came from this guy Dante, [who wrote] essentially a mainstream thriller, if you will, of his day. That was fascinating to me and very hard to resist."

Brown relocated to Florence, where Dante lived and from where he was exiled, to immerse himself in the poet's world. Brown's own fame helped open doors to normally secret areas of museums and palaces that he has used as settings for his chase scenes.

"All the secret passages in this novel are accurate," he says. "I've walked through them.

"We got a secret tour of the Palazzo Vecchio. I had this great experience where I got to the end of a secret passage and you push on this wall and the wall spins and I stepped out into the map room.

"I had pushed my way through a map of Armenia that a whole lot of people were looking at. These were tourists who thought, 'This is crazy, I'm in the Palazzo Vecchio and Dan Brown just stepped out of a wall'. They felt like they were in the novel."

One downside of his fame, though, is that there is intense speculation over what he is writing about next.

That meant that while in Florence, he feigned interest in lots of things that were utterly irrelevant to the novel in order to throw his hosts off the scent.

"There is a little cloak and dagger when I'm researching," he says. "Usually, half of what I'm looking at is for the book, and half is to create the illusion that I'm looking at something else.

"A lot of people assume, [because] you're writing about Dante, it's got to be about the church. Dante was very critical about the church, and I think a lot of people wanted to draw that line with me and say, 'That's where he's headed'.

"This book isn't about the church. It's referenced in a few places but it's not about the church."

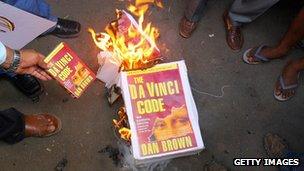

The Da Vinci Code drew protests around the world, including being burned in India in 2006

That may have been a logical assumption, given that Brown's most popular and notorious work The Da Vinci Code famously raised the ire of the Catholic Church by claiming the church had been involved in an age-old cover-up over the fact Jesus had married Mary Magdalene.

In Inferno, there is no historical conspiracy. Instead, Langdon has to stop a new plague being unleashed by scientific genius Bertrand Zobrist, who believes the only way to save the world from the consequences of rampant overpopulation is to wipe out a large proportion of the human race.

"I want to stress that this is not an activist book," Brown says. "But overpopulation is something that I'm concerned about.

"I talked to a lot of scientists who are also concerned about it and I came to understand that overpopulation is the issue to which all of our other environmental issues are tied.

"For example, things like ozone, where do we get our clean water, starvation, deforestation. These we consider problems. But they're really symptoms of overpopulation. So overpopulation to me seems like the big issue."

In the story, Langdon and Zobrist both believe they are saving the world.

'Horrific' idea

"I always try to choose the grey area and argue both sides," Brown says. "If I've done my job, you close this book saying 'Oh my God, what an enormous problem, and there is no simple solution, and I kind of see Zobrist's point.'

"I mean it's horrific. But the idea is that there is this moral, ethical and scientific grey area and you're left to ponder the ideas. I don't have an answer."

The consequences of Zobrist's actions may be unthinkable, but Brown has made sure the scientist's arguments and accompanying graphs, which illustrate the pressures humans are putting on the planet, are persuasive.

"It is," Brown says. "I was very persuaded. And the reason I think Zobrist is such an interesting character is because you can say, is he a madman or a genius? Or a little of both?

"There are moments in the novel, or at least when I was writing it, when I thought, wow, Zobrist may save the world here. Maybe this is how far we have to go to stop this."

He pauses before quickly adding a final "I don't know" to emphasise that he is not actually suggesting such an extreme solution.

"I don't have an answer," he says. "If I did, I wouldn't be writing novels, I'd be trying to help out for real."

- Published16 May 2013

- Published14 May 2013

- Published14 May 2013

- Published21 February 2013

- Published15 January 2013