Too famous to see?

- Published

Las Meninas depicts Velazquez (in a self-portrait) alongside the Spanish Royal Family in 1656

Diego Velazquez's Las Meninas, external is one of the most famous paintings ever produced. The public admire the grandeur of its size and subject, artists drool over the conceptual nature of the composition. It is iconic.

So much so, that Mat Collishaw - one of the original Young British Artists, external - became a little worked up over seeing it for the first time. He feared he might suffer from Stendhal's Syndrome - a psychological reaction that can occur when a person is exposed to a very well known, very beautiful painting - which can lead to palpitations and dizziness. It's a sort of art Beatlemania.

Mat wanted to have a direct relationship with the picture: To feel as if he was seeing it in the artist's studio for the first time. He figured he needed to find a way of eradicating all the propaganda and "poison" that had infiltrated his mind about the painting, which he worried would neuter his own critical faculties. His aim was to look at the picture and have an unmediated reaction; to silence the hundreds of voices in his head telling him how magnificent it is and why.

He came up with an elaborate plan, external.

Back in his London studio, he persuaded a friend to place a blindfold over his eyes, escort him by taxi to Heathrow, catch a flight to Madrid, lead him into the Prado museum, and position him in directly in front of Velazquez's Las Meninas. Only at this point was the blindfold to be removed. For three minutes.

After which, the blindfold was to be put back on and the whole charade repeated for the return journey back to the London studio. Whereupon Mat would remove the blindfold and have a think.

"Did it work?" I asked.

Mat Colishaw en route to see Las Meninas

"No," he said. "It had made the situation worse."

Instead of clearing his mind, it added yet another layer of reverence to those in which museums routinely wrap and present their most well known works. The grand entrance, stark lighting, glorious frame, hushed tones and attendant security guards are all part of the quasi-religious theatre.

The experience of seeing Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is not designed to encourage you to look at it like a painting in your local gallery; It's intended to be akin to a visit to the altar, or the celestial end point of a pilgrimage. Visitors don't come to see, they come to pay their respects.

When a painting becomes an icon, a psychological semi-translucent veil is placed over the work that partially obscures it from us. We can't see it afresh, we have already been told what to think, what to see and what to feel. The subject of the painting stops being what the artist chose to depict, but the object itself and what it represents.

No painting leaves the artist's studio as an icon. It becomes one over time. What then, causes the transformation?

We know certain images can become iconic through simplicity of design, openness to interpretation and relative ease of reproduction - the Apple logo for example. But that isn't enough. Even overwhelming approval is not sufficient to turn a painting into an icon, although it is a constituent part of the process. No, what turns a painting into an icon is fame.

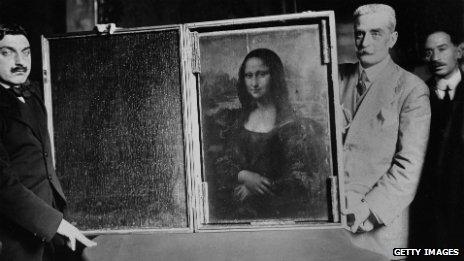

The Mona Lisa has not always been such a revered object. Arguably, that happened when it was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, and became an international cause celebre, routinely labelled as "the most famous painting on the planet".

The Mona Lisa was returned to the Louvre in 1914, three years after being stolen by employee Vincenzo Peruggia, who believed it should be returned to Italy

We should count ourselves fortunate that the work of several important artists has not become iconic and is therefore fully available for us to all enjoy. Paul Cezanne, for example, was the greatest painter of the modern period but not one of his many masterpieces would be considered an icon. He's not famous enough. And yet when he died in 1906, having set the world on a path to modernism, it was his paintings that led to the creation of a twentieth century icon.

Cezanne's death created a vacuum and challenge: Who would or could pick up the great man's gauntlet? Which artist had the wit, wisdom and wherewithal to take the "Master of Aix's" discoveries and innovations to the next stage? There were only two genuine contenders: Matisse and Picasso.

The two rivals and occasional friends got to work. Matisse continued his colour-saturated experiments with Fauvism. Picasso went back to his Bateau-Lavoir studio in Montmartre and painted.

And painted.

And painted.

Until, eventually, he was ready to show his own singular response to Cezanne's investigations into perspective and abstraction. He asked a few select friends from the more radical end of the city's avant-garde to drop by his studio and take a look at his unfinished canvas.

He expected some informed criticism to help him complete the picture. He didn't expect to the roundly abused. But he was.

One by one, the hipsters arrived, and one by one they left shaking their heads - not just at the size of Picasso's enormous canvas - but also at the magnitude of his failure. Matisse exploded, accusing his fellow artists of mounting an assault on art, and of trying to bring the modern movement to a premature and calamitous end.

Even Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet and critic, who had long been a supporter and champion of Picasso's work, was flummoxed by the artist's change in direction. Why, he asked, had his gifted young friend turned his back on everything that had made him successful? Another artist joked morbidly that one day Picasso would be found hanging behind "his giant canvas".

The painting was a failure. Picasso removed it from its stretchers, rolled the canvas up, and left it unfinished at the back of the studio. And there lay Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, external (1907) for many, many years, unloved and unwanted, gathering dust.

It is quite possible, if Picasso had died the day he painted Les Demoiselles that neither he nor his painting of five awkward-looking, two-dimensional prostitutes parading their wares in front of the viewer would be any more than footnotes in the story of modern art.

.jpg)

To what extent is our reaction to Les Demoiselles shaped by reverence for Picasso's work?

But he didn't. He went on to found Cubism (with Braque), which led to Modernism and Picasso becoming the most famous artist in the world. And his entire oeuvre being reappraised.

When the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) acquired Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in 1937 it was still a largely unknown work, although Picasso had eventually sold it to a collector in 1924. It had very, very rarely been seen in public.

Which meant that, when MoMA displayed it for the first time in 1939, it was able to promote it as something of a revelation that marked the moment the now-celebrated Picasso changed art forever. MoMA presented the once derided image as the foundation stone of Modernism and turned it into an icon.

When we look at Les Demoiselles today we don't simply see a large blue, white and pink painting inspired by Cezanne and African masks, as Matisse and Apollinaire once did. Our experienced is shaped by the romanticism of the picture's past, by its links to our present, and our understanding of its place in the canon.

We could dismiss it, but that would be idiotic. The best we can do is peer past the crowds; enjoy it for what it has now become, and tick the box.

Alternatively one could go to the Courtauld Gallery, external in London, lose oneself in its un-crowded galleries and wallow in its exquisite collection of less celebrated Cezanne masterpieces. I think that's what Picasso would have done.

Arts Editor Will Gompertz explores what makes a work of art into an icon.

The Editors is broadcast on BBC One on Monday 20 May at 23:20 GMT. It is also on BBC World News.