I Am Breathing documentary charts MND sufferer's battle

- Published

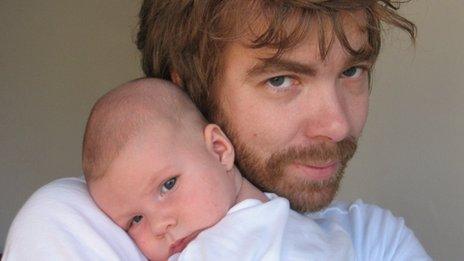

Neil wanted to write a letter to his infant son Oscar

Architect Neil Platt was just 33 with a baby on the way when he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND).

The condition, which leaves sufferers unable to move, to swallow and eventually to breathe, had already claimed the lives of his father and his grandfather.

To date, there is no known cure for MND and few who are diagnosed live beyond four years.

Knowing he had only a short time to live and concerned about what that would mean for his young son Oscar, Neil put together a letter and memory box for him.

He also resolved to share his disease with the world on a blog Plattitude, external, which documented his thoughts and feelings, often lacing his writing with black humour.

It was that blog that would eventually lead to the new documentary I Am Breathing, external, set to have its European premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival later this week.

The film was co-directed by Morag McKinnon and Emma Davie.

Film-maker McKinnon was friends with Neil and his wife Louise while the three studied at art school in Edinburgh. They kept in touch in the years afterwards and when Platt was diagnosed with MND in 2007, she was one of many friends who visited him.

But it was Neil himself who instigated the project using his blog as a means of raising awareness of MND.

McKinnon, who describes the documentary as having resulted through a "network of friendship", says: "He basically said he wanted to take some action and he asked his readers 'anything you can do... anyone you know'."

McKinnon, a director of short films and dramas, immediately contacted her friend Emma Davie - a documentary maker.

However, even with a willing subject on board, Davie admits a number of ethical concerns made her initially reluctant.

"I really felt I couldn't do this for a number of reasons," she explains. "I wasn't sure if it was ethically the right thing to do. Even if someone wants to be filmed, sometimes I feel that they might not be aware of the complexity of how that will affect their life."

A year later in 2008, both directors were confident they could make the film and started shooting, but it was McKinnon who struggled.

She now admits her closeness to the family was a genuine obstacle as she tried to maintain the dispassionate eye of the documentarian.

"I had real difficulty in the beginning," she explains. "Because I had visited a number of times beforehand to do the dishes or make cups of tea and I just went into this default mode of trying to help.

"Emma had to rein me in and say 'No we're here to do something else and it's just as useful in the long term'."

Rather than referring to her subject, McKinnon calls Neil a "collaborator" who took an active interest in how a film he would never live to see was being put together.

He even offered his suggestions about the soundtrack. It was Neil who suggested the film should open and close with the sound of the ventilator which helped him breathe "because it's what I hear from morning to night".

Davie agrees with McKinnon, saying that from very early on, it was Neil who was was much in the driving seat.

"Neil was really clear that there were no holds barred and he wanted us to film whatever we felt was right, even towards the very end he would have been happy for us to film him."

Platt spends much of the film hooked up to a ventilator that breathes for him

I Am Breathing is not an easy watch but the film isn't without moments of black humour as Neil describes trying to end his mobile phone contract.

"Can we offer three months more for free sir?" he is asked.

When Neil's power of movement leaves him, voice-activated software helps him dictate his blog. Never losing his sense of humour, he describes his disease as continuing to be "a right royal pain in the arse".

In the heart-wrenching final scenes, a barely conscious Neil dictates his last blog entry to Louise in a whisper. It treads close to the line of taste but MacKinnon insists it was Neil who again demanded the camera be present.

"There was a point when we stepped away and we didn't feel it was appropriate to be there - but those last bits of filming weren't filmed by us. They were filmed by the family and that was Neil's choice."

MacKinnon continues: "The camera falls away as Neil starts choking and he says 'Camera' and that was him saying, 'I'm still focused on the filming even though I'm in this dreadful situation.

"That's how great his need to communicate the disease was."

The cause of MND is still unknown and for some 10% of the 5,000 people in the UK suffering from it, it is a genetic condition.

Half of those people die within 14 months of diagnosis. The film's production notes reveal that while more than £300m is spent annually on cancer research in the UK, the average spending on MND research is £2m.

Neil died in 2009

Yet the film-makers have chosen to avoid turning I Am Breathing into a political tool.

"Neil, when we first began filming, was talking a lot about the need for more funding and we had long chats and told him it was great what he was saying, but those were facts that could be said in a newspaper article," says Davie.

"I said the power of film is that it can show you as a human, trying to be a father, trying to live as best you can while this disease is ravaging your body. I said let's show you as you are rather than trying to be a campaigner and that paradoxically will make it more effective."

The film will be screened internationally on 21 June - MND Global Awareness Day - which will coincide with its release in UK cinemas.

Visitors to the website are encouraged to set up their own screenings and, to date, screenings are happening in places such as China, Bahrain, India and Kosovo.

"People are being very creative, someone's showing it in a boat, there are screenings in Canada, houses in Yorkshire, town halls and churches in America.

"It's truly inspiring," says Davie.