Taking a fresh look at LS Lowry

- Published

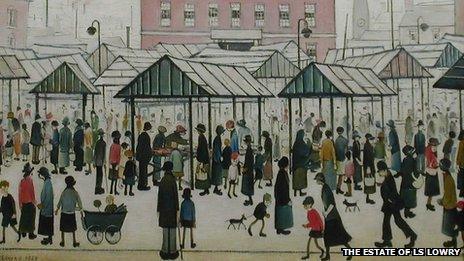

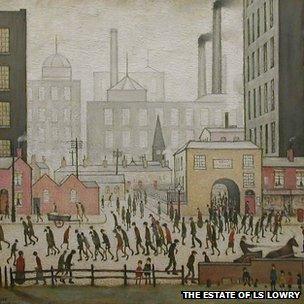

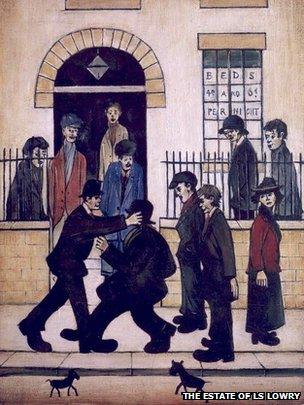

Few artists have divided opinion as strongly as Laurence Stephen Lowry. He is adored by millions, but many in the art world have been more critical - some say due to an anti-northern bias. As Tate Britain in London launches the biggest Lowry exhibition since his death in 1976, is it possible to look beyond regional views?

"The thing about Lowry," the art correspondent from the Times says on our first day of recording, "is that there's a certain 'Where's Wally?' aspect to his paintings."

As northerners, presenter Michael Symmons-Roberts and I do not know whether to chuckle at a decent gag or kick him in the shins.

The thing about Lowry, it seems, is that he still has the power to turn things tribal, to redraw the battle lines between capital and provinces with a flick of his brush.

The two of us, freshly delivered at Euston train station that January morning for the press launch of Tate's massive new exhibition, genuinely hoped that by now this would not be the case; it becomes clear that is the wish too of curators TJ Clarke and Anne Wagner, who are as keen to talk in their presentation about the influence of French art on Lowry as they are to rake up tired old debates about regionalism.

Come the questions from the critics, though, the old metropolitan disdain is thinly veiled at best. "Why isn't this exhibition at the Lowry Gallery in Salford?" asks one. Not "what is it about his painting that merits an exhibition?", you notice. It is similar to the snobbery that cannot abide that Shakespeare came from the sticks. Well, tough. He did.

Myth of a truculent misanthrope

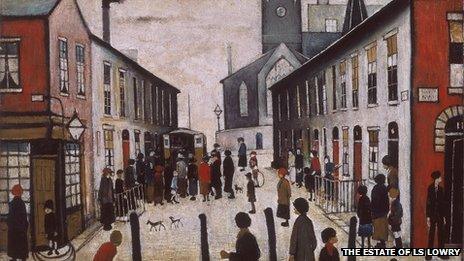

Seamus Heaney makes the case that some of the most enduring poetry is born away from the centre, and Lowry's example suggests that might also be true in art.

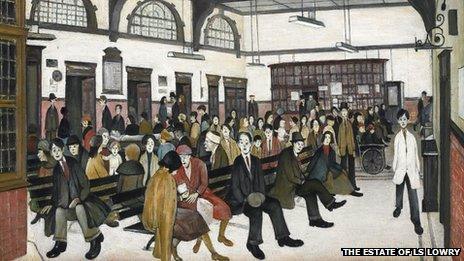

It is not simply that he lived in the industrial North West of England rather than a fashionable mews in London that set him at a distance, but that for decades he punched the clock as a rent collector instead of knocking off a portrait in the afternoon then heading off to some bohemian soiree.

As contemporary critic Edwin Mullins put it: "He doesn't belong to anybody. He belongs to a different kind of tradition, that of the English isolated eccentric. They are all isolated freaks."

The myth of Lowry himself as a truculent misanthrope, "buttoned tight against the weather and the world", as the Observer dismissively described him recently, only contributes to the notion that this is a man and artist we would all be better off without, even though he is one of the handful of British artists most of us could readily identify.

Lowry studied painting part-time in evening classes, and later only painted at night after work

The art establishment uses this image of loner Lowry like a father discouraging his daughter from dating someone she adores by saying he is a bit moody, rather than admitting it is because he did not go to the right school. The trouble is that that image simply does not hold up.

Frank and strident, clever and funny

Listening to the archive of Lowry talking, for example in the home recordings belonging to long-term friend Simon Marshall, the artist is warm and far from "buttoned tight against the world".

In the numerous interviews given to the BBC he is frank and strident, certainly, but he is also very clever and very funny: three parts AJP Taylor, one part John Lennon. Hearing him run rings round the clipped Received Pronunciation interrogation of the questioners fills a northern chest with a "Stick that in your pipe!" pride.

But it should not, it really should not. Establishment sniffiness might make the hackles rise, make us feel the need to defend one of our own, but that defensive proprietorial attitude is finally misplaced. We do not own Lowry, any more than the South of England owns Dickens, or France owns Toulouse-Lautrec. Anyway, thumping the tub as chippy northerner gets extremely dull extremely quickly.

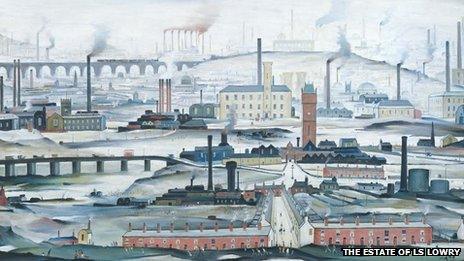

Also, even if the particular landscape of the industrial North provided Lowry with his chief subject matter, his paintings were amalgamated impressions rather than photographic documents. "I am not a recorder," he insisted, "I've never intended to interpret the industrial landscape as purely the industrial landscape. I'm recording my impression of the industrial landscape. I've always said that."

Lowry was appointed official artist for the Coronation of the Queen in 1953

So, having been drawn into those same old debates despite our best intentions, we were given a salutary jolt when we visited the Lowry in Salford and stood in front of a painting called The Sea from 1963. Its complete lack of content, other than the sea and the sky, means there is no clue about where the painter comes from. What counts is the sheer quality of the work and that, regardless of the painter's origin, his or her terrific ability is beyond doubt.

'Valuable part of English tradition'

That surely is the point, and the one we certainly arrived at by the end of our recording. If you cut LS Lowry into slices, I'm glad to say the word running right through his body wouldn't be "northerner", it would be "artist". For that is what he was: a serious, dedicated, talented artist with a singular vision.

And when Mullins put him in a line of isolated freaks, he added that as a man Lowry himself was in no way freakish. He added that this line of painters was a "very, very valuable part of the English artistic tradition", confirming the point by including in it the likes of Stanley Spencer and William Blake.

Pretty good company to be in, even if they were both southerners.

Lowry Revisited is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 24 June at 16:00 BST. Or listen again on iPlayer.

- Published1 June 2013

- Published26 January 2012