Killers' letters used in Edinburgh play

- Published

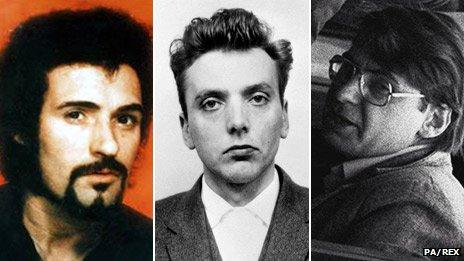

The play is based on letters by (L-R) Peter Sutcliffe, Ian Brady and Dennis Nilsen

Letters sent by Britain's most notorious serial killers to schoolchildren, supermarket shelf-stackers and lonely women have been used by the creator of TV drama Taggart for a new play at the Edinburgh Fringe.

Moors Murderer Ian Brady, who killed five children in north-west England in the 1960s, tells a schoolboy his favourite film is Bambi.

Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, who murdered 13 women in the 1970s and 80s, assures an infatuated woman he is no longer dangerous because he now ignores the voices in his head.

Dennis Nilsen, who killed 15 predominantly homosexual men in his London flat and disposed of their bodies by boiling body parts in his kitchen, gives relationship advice to a confused Waitrose worker who is looking for a gay affair.

This is an unholy trinity of the most evil men in modern Britain.

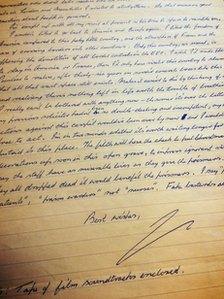

A dozen letters from Ian Brady to a schoolboy were bought from a dealer

The revelations - which range from the chilling to the surreal to the mundane - are contained in unpublished letters written from their cells to pen pals in the outside world, explains Taggart creator Glenn Chandler.

Chandler has acquired correspondence from these serial murderers. They now form the basis for his play Killers.

A dozen letters written by Ian Brady to a schoolboy and 15 from Nilsen to the shelf-stacker were bought from a dealer, Chandler says, while 150 from Sutcliffe to a woman who wanted to marry him came from an "anonymous source".

"Believe me, lots of women write to the Yorkshire Ripper and fall in love with him," Chandler says.

"The strangest people become fans of serial killers." As the writer of Taggart, which ran for 27 years until 2010, Chandler has spent more time than most trying to get into the minds of murderers.

In his new play, the three men are portrayed on stage at their writing desks.

"The exciting thing about the letters is the little mundane things about them, such as Ian Brady talking about his favourite film, which happens to be Bambi," Chandler says.

"And the avuncular advice that these serial killers give their fans on the outside. Ian Brady is advising his schoolboy correspondent to stick with school, and not follow a life of crime like he did, and become a mechanic or a chef and he picks him up on his handwriting.

"Dennis Nilsen likewise. One gets the impression the boy is writing to him saying, 'I'm very lonely I don't have any friends.' Denis Nilsen is writing saying, 'Look, you've got to go out and make friends.'

"He tells Denis Nilsen that he wants to go out and have a gay relationship. Denis Nilsen says, 'Remember, a gay relationship is a two-way thing. You must give and take.' Yet here's a guy who killed 15 of them and chopped up their bodies.

"So some of the ironies in the letters are absolutely fascinating."

There is "a fantastic amount of insight" into the psyches of the killers, Chandler suggests.

Brady refuses to answer his young correspondent's questions about his crimes and shows no remorse, according to Chandler, who says Brady asks the boy: "Why are you interested in me?

"Why aren't you interested in an American Air Force pilot who drops bombs on a village in Iraq? Is it because he kills with official permission and I don't kill with official permission? Is that what makes me so interesting?"

Chandler adds: "He goes on about that but he won't talk about his crimes.

"The Yorkshire Ripper, on the other hand, he does. He says to his lady correspondent, 'I'm cured now. I still hear the voices telling me to do these bad things, but I know that they're bad and I don't listen to them any more. If I got out now I'd be all right, I'd be perfectly safe, I wouldn't hurt you.'

"He says, 'I know all the things I did were bad and I wish I could put the clock back and not do them.' You get the feeling that there's not a lot of sincerity there. 'The things I did were bad' is a bit of an understatement."

The trio are linked by a sense of self-importance that comes from the knowledge that they have a reputation as "criminal celebrities", Chandler believes.

"If you're Peter Sutcliffe and you get 50 letters a month from different women… He never had that when he was a lorry driver."

Gareth Morrison (L) plays Sutcliffe, Arron Usher (C) plays Nilsen and Edward Cory plays Brady

In Brady's recent mental health tribunal, he unsuccessfully argued for a return to prison from a secure hospital. It was his first public appearance since his trial in 1966 and was criticised for simply giving him the attention he craved.

Won't a play in which they are centre stage feed their egos even more?

"I would respond to that by saying that for me, the most interesting aspect of the psychology is the people who are writing to the serial killers," Chandler says.

"The schoolboy, the guy who works in Waitrose as a shelf-filler, the woman who is in love with the Yorkshire Ripper. It's really the psychology of the writers and why they write reflected through the killers' letters that I think is the main focus of the play."

That is a little unconvincing given that it is the killers who are portrayed on stage, not their pen pals. Chandler says he only has the inmates' side of the correspondence.

If the show is feeding the reputations of these "criminal celebrities", so have countless books and TV dramas.

"I think they get enough publicity without a Fringe production to be honest," Chandler says.

Still, word about the play has reached Nilsen. Chandler says the killer contacted him through a third party after an early performance in Brighton.

"Someone had reported back to him and he said to me, 'Glenn, bear in mind I'm just a 68-year-old geezer and I accept that people will always want to write plays or books or articles about me.'"

Killers is at the Assembly Rooms, Edinburgh, from 1-25 August.

- Published28 June 2013

- Published13 June 2013

- Published22 May 2011

- Published16 July 2010