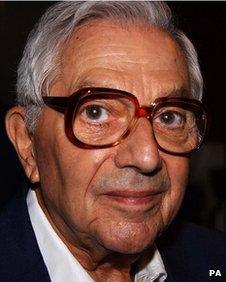

Kubrick recalled by influential set designer Sir Ken Adam

- Published

Peter Sellers, pictured with Sterling Hayden, played three roles in Dr Strangelove

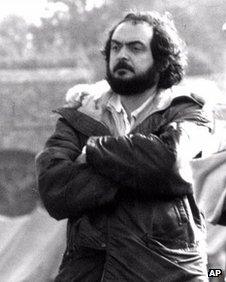

Steven Spielberg told production designer Sir Ken Adam his work for Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove included the best movie-set ever built. Kubrick's dark comedy is now regarded as a Cold War classic. Fifty years on, Sir Ken remembers his time working for Kubrick as a magnificent adventure - if you could take the stress.

Sir Ken Adam sits in his house in central London and summons up memories of Stanley Kubrick. His affection for the director is obvious and at times there's real emotion in his voice.

"I was incredibly close with him. It was almost like an unhealthy love affair between us. And I had a breakdown eventually."

Sir Ken was born Klaus Adam in 1921. The prosperous Jewish family fled Germany as he entered his teens but his Berlin accent remains. Even in retirement he is British cinema's doyen of production design, whose credits include most of the Bond films up to Moonraker (1979).

When summoned in 1963 to a London hotel to meet Kubrick he was aware the American director could be a demanding taskmaster. But the encounter proved unexpectedly easy.

"We were sitting across a table in the living room and all the time we were discussing Strangelove I was doodling. Immediately Stanley was fascinated by my doodles so we got on like a house on fire. Most days during production I drove him to the studio in my E-type Jaguar.

"I recommend this as a way to get to know your director.

"You know, in some ways Stanley was naive and we were both young and full of enthusiasm. At first I thought well this is amazing: here is a man who is supposed to be one of the most difficult directors ever and he accepts everything I've designed. All I have to do is hand it to the art department and they will get cracking. Well, little did I know."

The set everyone remembers from Dr Strangelove is the enormous war room. It is like something out of a dream - or perhaps a nightmare.

"It came as a big shock when two or three weeks into filming I realised Stanley wasn't so easy-going after all. I'd designed the war room as a split-level set with actors on each level but he came to me and said Ken what the hell am I supposed to do with 60 people on the upper level?

"They're standing around with egg on their faces doing nothing - get rid of the upper level. I said: 'Stanley, now you tell me. But of course he was right'.

"We had big rows because on other films I'd been used to telling the director where to do his establishing shot from. But Stanley said the hell with you I'm not putting my camera there - and you'll thank me in the end."

The war room is an acknowledged classic of movie design and Sir Ken can't resist quoting the biggest compliment he ever received.

"I was in the States giving a lecture to the Directors Guild when Steven Spielberg came up to me. He said 'Ken, that War Room set for Strangelove is the best set you ever designed'. Five minutes later he came back and said 'no it's the best set that's ever been designed'."

Sir Ken Adam designed the sets for seven James Bond films

But by the end of the Strangelove shoot Sir Ken had resolved never to do another Kubrick film: the process had been too exhausting. "We agreed to part as friends and I was so relieved."

But there was to be a second and more difficult chapter in the men's relationship.

"In 1972 he approached me about designing Barry Lyndon but I think he decided I was too expensive and he employed someone else. Three weeks later I was in the south of France doing a film and the phone went.

"It was Stanley sounding like a little New York boy: he said the designer hadn't worked out and he needed me. He schmoozed me into doing the film and I was never happy about it."

Barry Lyndon was an ambitious historical epic to be shot on location. But there was a problem: Kubrick wanted to find locations while barely leaving his family home in Elstree, north of London.

"So we set up in his garage a little war room, with Ordnance Survey maps on the walls and pins everywhere. We had an army of young photographers to go looking at buildings and possible locations and every evening we looked at what they'd done.

"He would be enthusiastic about a particular bed or whatever in a slightly voyeuristic way.

"But we'd have big arguments because I would say: 'No that's Victorian but the film is set in Georgian times'. Well Stanley was so competitive that he bought almost every book available on Georgian architecture so he could argue with me. But none of this was getting the movie made because the buildings and peaceful locations he wanted just don't exist anymore near London.

"It was nerve-destroying. But after five months I got Stanley to switch production to the Republic of Ireland - which I thought was my masterstroke."

Stanley Kubrick had a reputation as a demanding director

As Sir Ken recalls it, once in Ireland Kubrick changed totally. "He saw himself as General Rommel, who he admired greatly. He equipped all of us with Volkswagens so we became a complete mobile unit driving around Ireland finding locations.

"I spent weeks being chased through fields by bloody bulls. I was going crazy but this was Stanley's character - with all his fears and anxieties he was relentless. "

When Letizia, Sir Ken's Italian-born wife, came out to Ireland she was shocked at his state of mind. She persuaded him to return to England and see a doctor for the sake of his health.

"So now I was in hospital in England with a breakdown. Stanley rang the hospital every day to see how I was doing and if I was still alive. The day I left he phoned me at home.

"He said: 'Ken you were right: we're going to change the way we're making the film and you'll love it. I'm sending a second unit to Potsdam in Germany to pick up extra material and I want you to direct it."

Sir Ken laughs. "Well I found that idea such a huge shock I had to go straight back to the clinic and check in again."

After Barry Lyndon, Sir Ken decided this time, whatever his admiration for Kubrick, the two would never work together again. It was a vow he adhered to with one brief and slightly bizarre exception.

In 1977, designing the Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me, Sir Ken had built a vast set at Pinewood studios. It included a supertanker which was proving hard to light.

"So I called Stanley up and asked him down to Pinewood to give me ideas. At first he said I was out of my mind but eventually he agreed to come on a Sunday when only security were around.

"He spent three or four hours with me telling me how he would light the stage. And of course the whole thing being in secret appealed to Stanley's sense of drama. But I knew we would never work together again. And Stanley didn't ask - he'd been so scared when he saw what happened to me half way through Barry Lyndon."

In 2003, Ken Adam received a knighthood - the first for a film production designer. Kubrick died in 1999 at the age of 70, one of the world's most admired and most demanding directors.

Vincent Dowd was talking to Sir Ken Adam for the World Service's Witness programme