Stephen King: Meeting the 'father of fear'

- Published

Stephen King talks to arts editor Will Gompertz

He arrived as if by teleportation: without a sound or visual cue. It gave me a jump.

"Crickey Stephen! How did you get here?"

"In the Tesla."

(It was teleportation!)

"The what?" I ask.

"The Tesla. My new car."

Stephen King, the father of fear, the crowned head of horror, stood over me and smiled a "howdee" sort of smile.

"Want to take a look?" he said.

I did.

The lanky 65-year old with an easy manner and a friendly air, took me on a guided tour of his snazzy new electric sports car. He'd been given it by his wife for his birthday and was obviously delighted to have a bright red motor with cool green credentials. It was mighty fast he told me, and had a range of around 250 miles.

That didn't seem very far for someone who lived in the middle of Maine, New England: a place where people will drive for a few hours to "pop over" to see some friends. I don't know if it would even manage a round trip visiting all of King's properties in the county.

He has several houses in the area. The interview took place in one. It was not his primary home, which is nearby, but a guesthouse (six bedrooms, huge garden, tennis court, lake!) that is extremely well appointed but barely used. Bought, I am told, not as a financial investment, but to stop the building of condos around the lake that would spoil the area's natural habitat and landscape. The house, like the car, was in showroom condition.

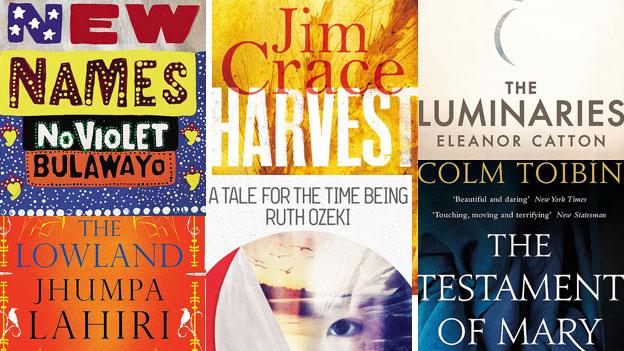

On a sideboard in the kitchen, for instance, were three pristine piles of books, unread and box fresh. One stack had Stephen King printed on the spine; another bore the name Joe Hill. Next to them was a slighter shorter column of novels by Owen King. Here was the physical manifestation of the most recent work produced by the householder and his two sons. His wife Tabby is also a successful novelist.

Pretty extraordinary, don't you think? Name another family, other than perhaps the Bronte's, which can boast that many best-selling authors.

I asked him if he thought he and his family have a literary version of The Shining: a sort of paranormal ability to channel stories. "I do," he said. And then added that he thinks all writers have the ability to go into a trance-like state of self-hypnosis where "you find yourself able to access all kinds of information" and from which a story emerges.

"People ask me what was it like to write Lisey's Story and I tell them I don't know: I was like dreaming awake."

King is a total pro when it comes to keeping the conversation on topic, which in this instance was to promote Doctor Sleep, the soon-to-be-published sequel to The Shining. He answered questions fully and thoughtfully, but generally found a way to weave in the new book. Not though, when I asked him about the early days.

He was a "brash young man," he said. Furious about the advantages he perceived the Ivy League crowd had over him, a clever but poor working-class boy without money or contacts to help him on his way.

To illustrate his point he recalled the time in the 1970s when Carrie and Peter Benchley's novel Jaws were about to be made into mass-market paperbacks by their mutual publisher. According to King it was Jaws that received all the marketing spend and not his book because the Harvard-educated Benchley hung out in the same uptown places and spaces as the bow-tied, hoity-toity posh publishing set.

Nowadays, having sold hundreds of millions of copies of his books, the anger and resentment has dissipated. He has all the material trappings and big-time contacts anybody could wish for, but has no interest in playing the high society game. He dresses in jeans and T-shirt, eats lunch at the bar in a local diner, and is content to hang out in his sparsely populated part of Maine (although he heads down south to Florida every winter to sooth the aching bones, the legacy of being knocked down by a truck in 1999).

He recalls, almost nostalgically, how vicious the critics were towards him when he started out, deriding him as a "genre" writer who was only interested in money. The Village Voice published a cartoon of King sitting at a typewriter greedily devouring the dollar bills it was spewing. It hurt "a lot" he said, but you must "never let them hear you yell".

Critical revulsion has largely turned to reverence, but I sensed the feeling of being one down still lurks within him.

Harold Pinter, I mentioned, tended to start a play with a single image in his head. It wasn't an opening scene, or the final act, but a powerful vision around which he would build a narrative. King stopped and looked up at a tree.

"I do that," he said.

"With Joyland it started with an image of a boy in a wheelchair flying a kite on a beach. And I live with that image for four years, looking for what was around him, and little by little it started to grow and then I sat down and wrote the story."

He pauses a little

"That's cool," he muses, and then asked for clarification.

'He said that, Harold Pinter?'

"He did."

"I love it."

- Published11 September 2013

- Published10 September 2013

- Published23 July 2013

- Published17 December 2012