Historic Japanese erotica reveals Tokyo’s sex secrets

- Published

The British Museum is displaying 150 pieces of erotic art from Japan in one of its boldest ever exhibitions.

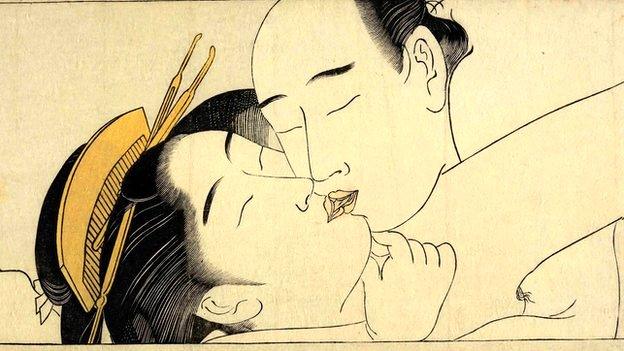

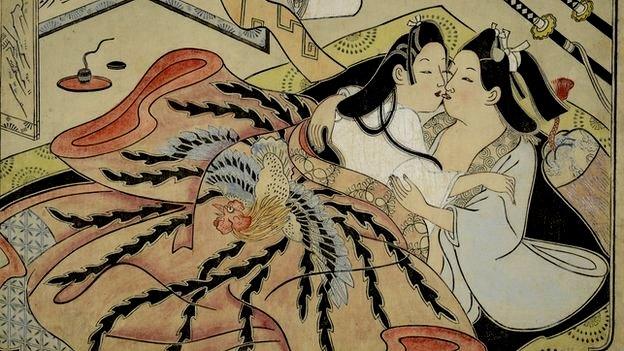

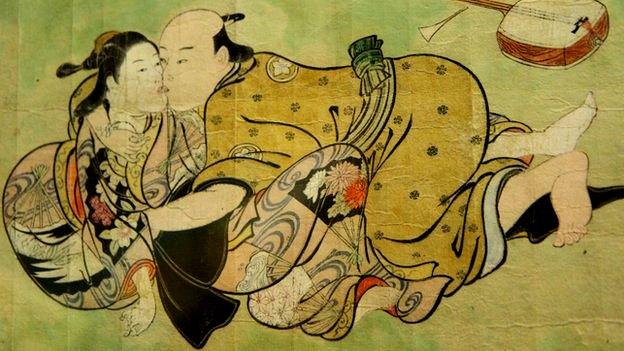

Known as Shunga, the pictures provide a perspective on sex quite different from European art of the same period.

The exhibition allows viewers to see the most intimate moments of Japan from a time when it was largely closed off from the rest of the world.

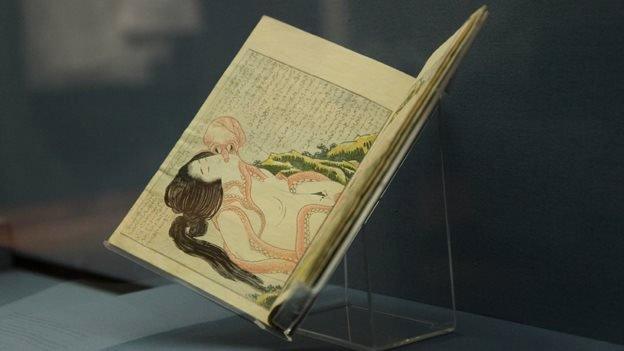

Most of the pictures are wood block prints, produced in Tokyo in the 16th, 17th and 18th Centuries and show a range of sex acts, often in explicit detail.

The term "Shunga" literally means "spring pictures"; a euphemism for the erotic art which flourished at a time when the city's population was growing rapidly and contact with the West was not allowed. They are also known as "pillow pictures" or "laughing pictures" and tend to show their subjects enjoying sex.

Most depict partnerships of men and women but there are some gay and lesbian scenes, as well as depictions of groups of people taking part in orgies.

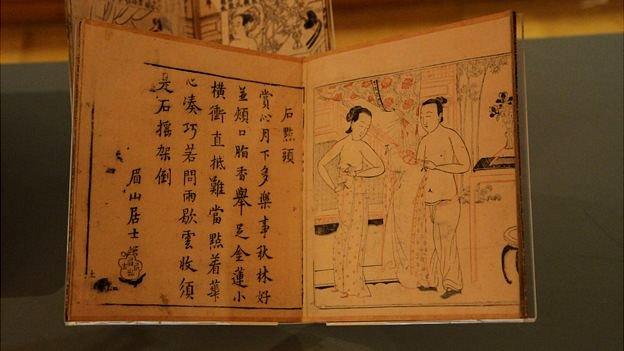

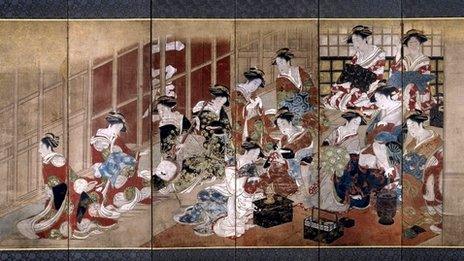

This image, from the 1780s, depicts the courtesans of Tokyo's Tamaya House

The pictures were sometimes sold in albums of 12 images, showing a range of different sexual situations. By purchasing a collection, buyers would not necessarily have to reveal which pictures they preferred to see.

Because of its explicit nature, the British Museum's exhibition can only be seen by people over the age of 16.

Other galleries have, in the past, regarded some Shunga as obscene and refused to show them. But, in recent years it has come to be accepted as a sophisticated art form, which provides an insight into the sexuality and gender politics of early modern Japan.

"Shunga are deep art. They are different from simple pornography," asserts Aki Ishigami from Kyoto's Ritsumeikan University, who is taking part in an academic symposium in London during the exhibition.

She says that the pictures were often enjoyed by women and form part of the "art of the floating world" which drew inspiration from Tokyo's so-called "Pleasure District", where musicians, actors and prostitutes provided entertainment for paying customers.

Sometimes albums of Shunga images were presented to young women before marriage to give them an idea of what to expect on their wedding night.

But art historian Dr Majella Munro says that, although Shunga had a role in sex education, this was not its main purpose.

"Shunga prints were not expensive and were bought by middle class urban collectors; they are artefacts of the popular culture of their time," says Dr Munro.

"Even though they were cheap, women were still unlikely to have had the means or motivation to buy them. They were sometimes bought by patrons of the floating world, wanting souvenirs of their visit to a world of pleasures that was only open to men to enjoy," says Dr Munro.

'Fine clothes'

To modern eyes, Shunga pictures sometimes resemble caricatures or contemporary manga cartoons from Japan, which can also be highly sexualised.

However, they rarely show completely nude bodies.

Professor Timon Screech from the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) says they need to be seen in context.

"The longstanding idea that the shape of the human body somehow encompasses perfection is drawn from a Greek ideal that was completely absent in all East Asian countries," says Professor Screech.

"It is much more likely that people thought beautiful, fine clothes were more sexually arousing than skin. Skin is what workers exposed in the street or what you saw at the bath house," he says.

"Whereas if you could run your fingers through some amazing piece of cloth - that was exciting. That is why the bodies are often covered in amazing fabrics."

The prints were well-known in Europe, with Toulouse Lautrec, Pablo Picasso and Aubrey Beardsley among the artists who owned sets

The first Shunga pictures to arrive in Britain were included in the cargo of a ship named the Clove, owned by the East India Company, which returned from a pioneering voyage to Japan in 1614.

It also brought back suits of armour and silk screens decorated with gold - presents from the Japanese Shogun (military commanders).

Some of the goods were sold at auction but the company confiscated the Shunga from the Clove's commander John Saris, considering it scandalous. It was later destroyed.

Professor Screech, who has written a book about Shunga, says the pictures rarely show compulsion or rape.

"The ultimate fetish seems to be that the person who I am doing it with actually wants to do it with me," he says.

In reality, prostitution was widespread in early modern Tokyo, when the city was known as Edo. Young women from poor backgrounds were often sold into the sex trade by their families. Venereal disease and unwanted pregnancies were common.

Art of the time - both erotic images and more mainstream depictions of women working as courtesans - presents a different picture, according to Professor Screech.

"Everyone is beautiful or gets beauty. There are a few stories of some vain person forcing their attentions on a person who rejects them but, for the most part, Shunga is celebratory of what can be termed, somewhat anachronistically, as a kind of free love - which we know was almost certainly not the case at the time," he says.

After the Shunga exhibition finishes at the British Museum it will take to the road and appear in other countries, including Japan.

Shunga - Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art runs at the British Museum from 3 October 2013 until 5 January 2014. Parental guidance advised.

- Published26 September 2013

- Published25 June 2013