The bumpy road to the National Theatre

- Published

The Denys Lasdun building on the South Bank did not open its doors to audiences until 1976

The National Theatre may be approaching its 50th anniversary on 22 October, but did the delays and obstacles it encountered during its creation result in a more versatile and creative establishment than elsewhere in Europe?

Disdain and hostility are not uncommon responses to major new cultural projects in the UK, but the venomous attacks levelled, over two centuries, against the idea of a national theatre leave a sour taste in the mouth even today.

Seymour Hicks, an early 20th Century dramatist and star of musical comedies, was against it being created and said: "The National Theatre! I wonder if there are really half a dozen people insane enough to think it will ever come into existence. We have national taxes, national schools, national horrors of every kind - spare us a national theatre!"

France has had a national theatre since 1680, Denmark since 1748 and Greece since 1901. The National Theatre in London is a youngster by comparison, which seems surprising, perhaps, for the country of Shakespeare. But this is a complex and singularly British story in which the arts, history, politics and changing ideas about national identity share the stage.

The story begins in 1848, when the radical publisher Effingham Wilson published a pamphlet called A House for Shakespeare.

His passionate plea for a national theatre seized the imagination and support of figures such as Charles Dickens and Matthew Arnold, but there was fierce opposition from powerful West End actor-managers who liked the non-subsidised status quo.

National Theatre associate director Michael Blakemore said the real reason there was not a national theatre earlier was because the language was English.

"Now, if you run a theatre in say Denmark, then the performances and the productions' lives end at the border, since very few people in Europe speak your language, so the only way you can support a national theatre is with public money," he said.

"But in England, what happened was that a great actor like Henry Irving and all the great 19th Century actors had another market for their work and that market was the US and Australasia. They all went on tour and made a fortune so they didn't need to be supported by public money."

Meanwhile, in the countries where there was a theatre subsidised by the state or court - such as the Comedie Francaise in France - the same classic plays tended to be performed again and again in the same old way.

'Bubbled up organically'

So, perhaps it helped that the London National was not established earlier by the state?

Nicholas Hytner, the outgoing artistic director of the National, is proud of the range of its productions and wholeheartedly agrees.

"It was a very good thing that it was never set up by the court or by competing principalities looking to express their prestige through their theatres and opera houses and orchestras and dance companies. It's a good thing that it always bubbled up organically from underneath," he said.

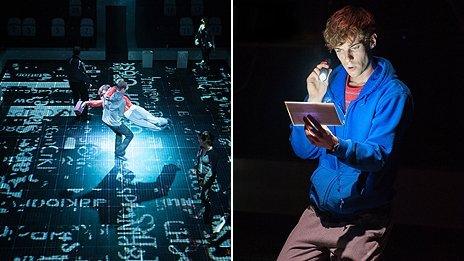

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time has been one of the theatre's recent hits

This bubbling up still took a surprisingly long time - with two World Wars intervening.

Playwright Michael Frayn says the optimism of the period immediately after World War Two when other national institutions were established may have been key in getting the National Theatre off the ground.

"The war fostered the idea that you could actually collaborate as a nation, you could get together to think about how to live your life," he said.

"And this made possible after the war a lot of things like the National Health Service and the so-called welfare state which would have been impossible in the context of the 1930s, and maybe the National Theatre rode on the back of that."

James Naughtie, the presenter of BBC radio programme Road to the National Theatre, believes in the powerful symbolic value of a third event.

"Post-war Britain was austere but exciting. From the rubble and the broken homes something better had to emerge. The National Theatre would become part of that process," he said,

"The Festival of Britain, the centrepiece of post-war culture, was erected in 1951, on the anniversary of the Great Exhibition, intended as a symbol of recovery and a confident trumpet call."

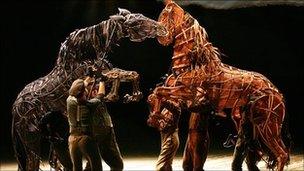

War Horse has been seen by more than 2.4 million people worldwide

At long last, during that year, a foundation stone was laid. It still took until 1963 for the establishment of the National Theatre, and the Denys Lasdun building on the South Bank did not open its doors to audiences until 1976.

What would Seymour Hicks - with his notion that less than half a dozen people believed in the idea of National Theatre - make of its success today?

Last year, one and a half million people attended National Theatre shows, either on the South Bank or at West End transfers such as War Horse, One Man, Two Guvnors or The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.

And that is not to mention the latest venture - National Theatre Live - which last year beamed performances of productions such as Frankenstein and Hamlet to more than three million people in cinemas across the globe.

The road may have been long, hard and boulder-strewn but, at a youthful 50, the National Theatre is more vibrant than ever.

Listen to the Road to the National Theatre on BBC Radio 4 on 6 and 13 October at 13:30 BST, or hear it on iPlayer.

- Published4 February 2013

- Published1 October 2012

- Published6 August 2012