Grayson Perry: Serious character and lovable artist

- Published

Grayson Perry: "I've called this series of lectures Playing to the Gallery and not, you may note, sucking up to an academic elite"

Artist Grayson Perry is delivering this year's Reith Lectures for BBC Radio 4. His series, titled Grayson Perry: Playing to the Gallery, will consider the state of art in the 21st Century.

Moments after he won the Turner Prize in 2003 Perry was ushered away from the warm embrace of the paparazzi's flashbulbs - which he was thoroughly enjoying - and taken to a back room.

The elite team of Tate staff who undertook the operation had performed this "star removal" procedure many times before. The paps had their picture - it was time for Grayson to meet the press.

The then 43-year-old artist had come as Claire, his female alter ego. Perry is not bashful in any guise, but as Claire he says he turns himself "up to 11".

His outfit for the night consisted of a bright pink Little Bo Peep dress topped off with a ginger-blonde bob adorned with a red bow. It is safe to say the press had hoped Grayson would win.

He didn't disappoint, talking openly about his work, sexuality and art. In the space of those few minutes he was asked hundreds of questions, most of which he batted away with erudite ease.

There was one though - presented as informed observation - that penetrated the facade of his self-confident bonhomie and drove into the artist's psyche, where it has remained ever since.

"What I can't work out about you, Grayson," the journalist mused, "is whether you're simply a lovable character or a serious artist."

"Can't I be both?" asked Perry.

That was 10 years ago, and still the question haunts him. It is at the heart of his four Reith Lectures, which in essence explore two subjects: what is art, and the nature of the art world.

They are about belonging and status, about what constitutes an artwork and those who deem it to be one. They are about identity. Perry is presenting them as Claire.

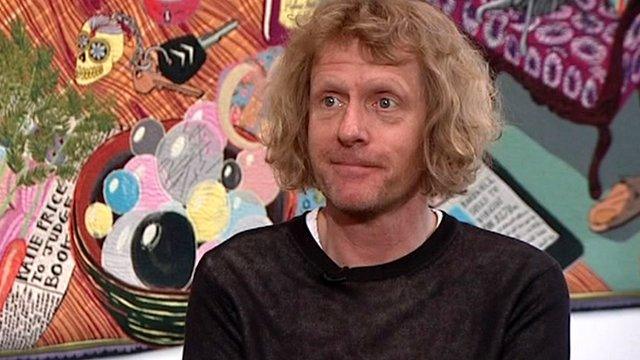

Grayson Perry in front of his tapestry entitled Map of Truths and Beliefs

This is his thing - to operate in the contested no-man's-land between art and craft, male and female, highbrow and low culture, as a serious artist and lovable character.

It is the same territory Andy Warhol occupied. It is the fertile ground on which modern art has flourished - the point where fine art meets everyday life.

I went to see him to talk about his lectures. He was in good shape, looking forward to moving into his new studio which is much closer to home.

"I checked out how far a mobility scooter could go and realised my old studio was much too far away," he says.

Perry's lovable character has made him a household name, seemingly en route to becoming a National Treasure.

He has used his natural warmth and good humour to great effect as a TV personality who can hone an argument and present it with flair, as the Bafta he won for his Channel 4 series on class testifies.

He loves an aphorism, a witty one-liner. Mostly they land, sometimes they don't.

"You know it's art when it's a boring version of something else," is one that he uses in his lectures that doesn't stand up to much scrutiny.

But he generally hits the spot.

"It's the middle brow that the art world worries about," is well observed, and the way he illustrates the point is reminiscent of the rambling narrative landscapes of his pottery and tapestries.

"Contemporary art is the city; the old masters the lovely rolling hills of the countryside. Craft is the suburbs, which the art world can't drive through quick enough."

Maybe not, but there are humps in the road, causing pause for thought.

Perry wonders, for instance, in his lecture called Beating the Bounds (with a riding crop as a prop, but no parish priest), when does craft become art and vice versa?

He takes photography as an example, a form of visual culture he thinks is "pouring into the world like sewage". He asked his friend - the artist/photographer Martin Parr - what's the difference between a smartphone snap and a revered photographic artwork.

"When the print is bigger than two metres and costs more than five figures," Parr replied. An employee of an auction house added that "it helps if it's in an edition of five".

Any investigation into the hoary old question of "what is art?" will lead fairly quickly to Marcel Duchamp.

The philosophical French artist, who like Perry had a female alter ego (his was called Rrose Selavy), is considered responsible for a century's worth of head-scratching and chin-stroking by decreeing that anything could be art.

Does our Reith lecturer think Duchamp's famous urinal (Fountain, 1917) is a work of art?

"I do," Perry says.

"At what point did it become so?" I ask. "When he bought it (from a plumber's merchants on Fifth Avenue, New York), when he signed it (R Mutt), or when he entered it for an exhibition (it was never shown)?"

"When it left the shop," he concludes after a pause so lengthy it is interspersed with several conversations on other topics. A detour that takes in his view of the work his peers are producing.

"Most contemporary art is rubbish," he says.

"Such as?"

"Well, Marc Quinn is a laughing stock. Gilbert & George's recent work is lame. Some artists have become museum supply companies.

"The worst are those that try to be global."

"Such as?"

"Anish Kapoor. Antony Gormley."

He talks of a "conspiracy of silence in the art world" and of collectors buying art as if they "were shopping for handbags."

He says that his answer to the problem of the crazy prices being paid for brand-name artists is to produce only a few works a year, such that the money he receives for them has some relation to the value of the materials used and time invested - an hourly rate which isn't completely out of whack with reality.

The only exception to the rule being his pottery charity dogs, which he "bangs out in an hour".

He reaches behind his chair and plucks one from a pile of bits and bobs in the corner. He unwraps the 10in object on which he has written "this time in yellow to make it seem unique".

"My record for one of these [at a charity auction] is £21,000."

He complains that there is nothing radical in art anymore, nothing shocking or surprising. It crosses my mind that maybe not being radical is in itself radical - art that isn't playing to the gallery or Capitalism's insatiable desire for novelty.

We talk about dogma in the art world and the codes of behaviour and attitudes that rule you in or out.

"Name me one right wing artist?" I ask.

"Well… [he thinks… laughs] Tracey [Emin]!" he replies - an artist he admires for "retaining her working class roots". Not so Beryl Cook, whom he thinks "failed even within the limitations of the type of work she was producing".

"Which wasn't art?"

"No," he replies, "an artwork has to address art history".

I think that's probably right, each new work just being "another link in the chain" as Cezanne once said.

Grayson Perry, Reith Lecturer 2013, is a serious character and a lovable artist.

The first of Grayson Perry's Reith Lectures will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday, 15 October at 09:00 BST.

Three more lectures will be broadcast at the same time on 22 October, 29 October, and 5 November. The programmes will also be broadcast on the BBC World Service and will be available to download.

- Published7 July 2013

- Published30 June 2012

- Published25 October 2011