Qatar's influence over the art world

- Published

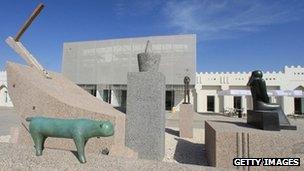

Qatar has opened a number of museums as part of its ambitious cultural programme

"Facts are stubborn things, but statistics are pliable," said Mark Twain.

The same could be said of all the power lists that are published, which are based on informed conjecture. They are a publishing construct, designed to draw attention to a publication and (typically) its specialism.

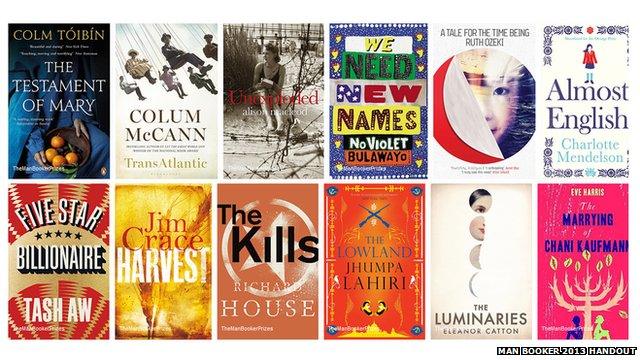

Today sees the publication of Art Review's Power 100, now in its twelfth year. The spin it has given to this year's chart, which is topped by Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani of Qatar, is that a power shift is taking place in the art world - away from publically-funded museums to the private wealth of individuals and collectors.

I'm not sure that's quite right. Or, at least, new.

Wealthy individuals have always been major players, from the Medici to Peggy Guggenheim; King George IV to Charles Saatchi. I don't think it's so much a power shift that's happening between public and private - more that the two worlds are converging.

To take a recent example, the Qatari royal family sponsored the Tate's Damien Hirst retrospective. It's now moved to Doha, where Tate director Nicholas Serota attended the official launch.

It's a symbiotic relationship based on mutual benefit, but one that has led to money being prized over art. It's telling that there are no artists in the top five of Art Review's list. The means has become the end.

World cup gallery?

Quite what Sheikha Al-Mayassa is planning to do with the trophy western art works she is buying is anyone's guess.

The 30-year old sister of the new Emir has been head of the Qatar Museums Authority for several years now. She has overseen the completion of the excellent Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the creation of a museum of modern Arab art, and is in overall charge of an exhibition programme that currently sees the Al Riwaq gallery space covered in Damien Hirst spots.

Sheikha Al-Mayassa is the sister of Qatar's emir

All of this is in the public domain. Information about her acquisitions of modern and contemporary western art is not. There has been much (informed) speculation as to what she has bought.

Major works by Warhol, Bacon, Rothko, Koons and Hirst are all thought to have made their way over to Qatar. As has, it is thought, Cezanne's Card Players (1895), the only one of this wonderful series not already in a museum collection, for which it is said, she paid a record-breaking $250 million.

What will become of these paintings and sculptures? Are they for private enjoyment, or perhaps to form the basis of a collection for a new museum of modern art to open in time for the 2022 World Cup?

And why are the Qataris spending so much on art (more than anyone else in the world according to the Art Newspaper and its art market expert Georgina Adam)?

International status and influence would appear to be a factor, along with a desire to compete with Abu Dhabi and Sharjah for the role as the region's cultural centre. Becoming a destination for tourism - both local and global - is likely to be part of the business plan: An investment made with the riches gained from selling oil and gas to prepare Qatar's economy for the time when those natural resources are less plentiful.

And, finally, to deliver on the Qatar National Vision 2030, as set out by her father, which aims to "build a bridge between the present and the future." The idea being to move the tiny state, in which there are only about 300,000 Qataris, from an oil and gas economy to a one that is knowledge-based.

- Published9 October 2013

- Published8 October 2013

- Published9 October 2013