How did Doctor Who reflect the real world?

- Published

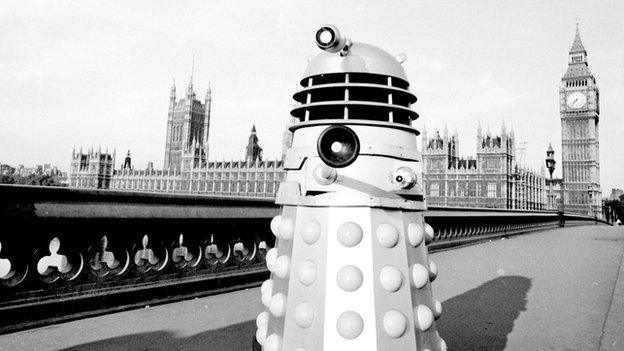

The Dalek Invasion of Earth

How did Doctor Who reflect what was happening in the real world?

When Doctor Who was born, at 17:15 GMT on 23 November 1963, the headlines were dominated by the assassination the previous day of US President John F Kennedy.

And the shock events in Dallas, Texas, eclipsed coverage of the deaths of writers CS Lewis and Aldous Huxley, also on 22 November 1963.

While that first trip though the doors of the Tardis may have had echoes of entering Narnia in Lewis' The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, it was the world-changing events of the previous decades that helped shape early Doctor Who.

"It is very much part of the post-[World War Two] era," says Graeme Burk, co-author of the book Who's 50 - The 50 Doctor Who Stories to Watch Before You Die.

"The science fiction of Doctor Who was very influenced by the post-war sci-fi of Brian Aldiss and John Wyndham and, to a lesser extent, CS Lewis.

"Early stories like The Daleks were written by people who grew up under the threat of Nazism and war."

The very first Doctor Who story, An Unearthly Child, saw the Doctor and his companions transported through time to the Stone Age where they encountered a tribe that had lost the secret of fire.

"There's dialogue about how fire is necessary but at the same time viewed as a threat by certain members of the tribe," says Burk.

"That story came about a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, so you can't help but see a metaphor for atomic weapons as things which could bring benefits or mass destruction."

The next story, The Daleks, introduced Doctor Who's most famous monsters.

The Tardis lands on the planet Skaro in the aftermath of a neutron war where two races survive - the Daleks, mutated creatures inside metal casings, and the pacifist Thals.

Coming less than 20 years after the end of World War Two, the allegorical reference to atomic warfare is not hard to spot, and many commentators draw parallels between the Daleks and the Nazis.

"The Cold War and WW2 come together in that first visitation from the Daleks," says Dr Graham Saunders, of the department of film, theatre and TV at the University of Reading.

"It's become a cliche that the Daleks are the Nazis. You could turn it on its head and argue that they all think the same way, so they are Communistic as well - they are both echoes from the war and the threat of the Red Terror."

The WW2 influence is even stronger in the second Dalek story, 1964's Dalek Invasion of Earth, set in the 22nd Century.

Tom Baker's Doctor meets Davros in Genesis of the Daleks

The story presents a vision of what things would have been like if Germany had won the war, says Mark Campbell, author of Doctor Who: The Complete Guide.

"Although it's set in the future the costumes and scenery is really 1940s-50s England. There are banners up everywhere and the Daleks do Nazi salutes. The images would have been very resonant to those who fought in the war."

When writer Terry Nation revisited the early history of Skaro in 1975's Genesis of the Daleks (with Tom Baker's fourth Doctor), the Nazi references were far more explicit.

Scientist Davros is intent on creating a master race while the military elite seek to exterminate the Thals.

As Dr Saunders notes, when Davros rants about racial supremacy in his underground lair it's like "Hitler raving in the bunker".

'Computers go mad'

Just as the 2013 Doctor Who story The Bells of Saint John featured new London landmark The Shard, the 1966 story The War Machines saw William Hartnell's Doctor visit the Post Office Tower (now the BT Tower) - which had officially opened the previous year.

The tower contains Wotan, a super-computer that creates an army of intelligent, armed mobile machines in order to take over the world.

The story tapped into the topical debate about technological progress. "I think Doctor Who is always more interesting when it's commenting on issues that are just bubbling under," says Dr Saunders.

"The War Machines is a story in which computers go mad and produce these war machines. It's The Terminator way before its time.

"The old Doctors were always sceptical of computers. In The Ice Warriors (1967) the Doctor does all the calculations himself - he doesn't trust computers . Although in new Doctor Who he seems much more comfortable with them, which says something about our age.

"In old Doctor Who up to the 1970s computers were these huge disembodied things with wheeling tapes, often with malign purpose."

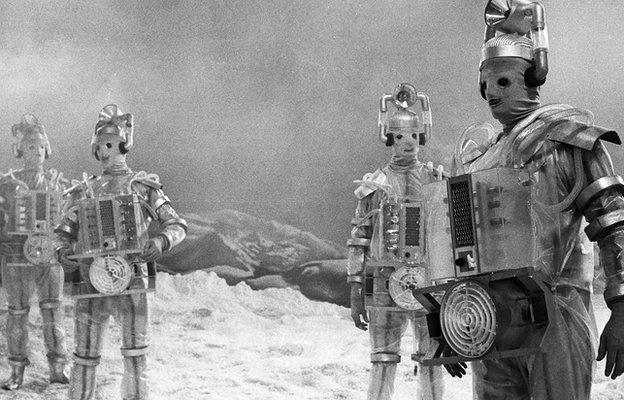

The Cybermen made their first appearance in The Tenth Planet

The War Machines were based on an idea by Dr Kit Pedler, Doctor Who's unofficial scientific adviser, who went on to create the show's second most popular villains, the Cybermen.

Making their first appearance in William Hartnell's final story, 1966's The Tenth Planet, the Cybermen were humans who had replaced their body parts with artificial organs.

Graeme Burk: "At that point organ transplants were coming in and Kit Pedler saw the next step as artificial transplants, so the Cybermen were very much created out of a response to that idea."

Just over a year after this story was broadcast, in December 1967, the first human heart transplant was carried out by Dr Christiaan Barnard in South Africa.

Aliens and the EEC

In the early 1970s, Doctor Who stories often reflected topical events such as the energy crisis (when oil-producing countries stopped exports to West), ecological concerns, industrial strife and terrorism.

In Jon Pertwee's second story, The Silurians (1970), a hibernating reptile race is awakened by tests on a new underground nuclear reactor. Later the same year, Inferno centred on a drilling project that releases a gas that turns people into werewolf-like creatures.

The Curse of Peladon, in 1972, mirrored a major political story at the time.

Pertwee's Doctor and companion Jo Grant arrive on the planet Peladon, whose king wants it to join the Galactic Federation, but his high priest opposes the union, claiming it will strip Peladon of its independence.

At the time the story was broadcast, British Prime Minister Edward Heath was in negotiations for the UK to join the European Economic Community (EEC).

The Curse of Peladon, with Jon Pertwee's third Doctor, referenced Britain's EEC membership

The metaphor may have been clear to adult viewers, but it would have gone over the heads of most children.

"It's actually an Agatha Christie whodunnit and it still works if you take away the stuff about going into the federation," says Mark Campbell. "It's a story with lots of monsters."

A return visit to the same planet in 1974's The Monster of Peladon was influenced by the miners' strikes of the period. The moderates and militants among the miners on Peladon allude to the real-life rift within the leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Eco-concerns, and the rise of groups like Friends of the Earth, were addressed in 1973's The Green Death, in which giant maggots emerged from the industrial effluent produced by Global Chemicals.

Dr Saunders detects the "shadow of Northern Ireland" in stories such as the Day of the Daleks (1972), which featured "terrorists" from the future, and Invasion of the Dinosaurs (1974) with armed troops on the streets - images which were familiar in news bulletins at the time.

'Video nasties'

Moving to the 1980s, the Colin Baker story Vengeance on Varos came shortly after the Video Recordings Act 1984 was passed in the wake of the press furore about "video nasties".

Colin Baker's sixth Doctor in Vengeance on Varos

In the story, the poverty-stricken people of Varos are kept entertained by screenings of public torture.

Mark Campbell calls it a "problematic story" because while it satirises on-screen violence as public entertainment, one episode contains a scene in which the Doctor delivers a quip after seeing a guard die horribly in an acid bath.

"I think the story says more about the power of television than the so-called video nasties," he adds.

Since its 2005 reboot, with Russell T Davies as show runner (2005-2010), the new series of Doctor Who hasn't shied away from political references ripped from the headlines.

In the episode World War Three, where aliens The Slitheen have invaded 10 Downing Street, there is a reference to "massive weapons of destruction" which can be deployed in 45 seconds.

"It's not hard to see that's a comment on the Iraq War," says Campbell, referring to the September 2002 dossier which became notorious for its suggestion Iraq could deploy weapons of mass destruction within 45 minutes.

The first David Tennant story, The Christmas Invasion, contains a scene which echoes former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's decision to sink the General Belgrano during the Falklands conflict in 1982.

Penelope Wilton's prime minister orders the destruction of a retreating alien spaceship, a decision condemned by the Doctor.

Graeme Burk detects fewer overt political references in the Matt Smith era of the show, with Steven Moffat in charge.

"Steven Moffat is a very different animal to Russell T Davies, who is a very political writer," he says.

"Moffat is more about taking something in the real world and making it scary or magical."

- Published21 November 2013

- Published19 November 2013

- Published19 November 2013

- Published11 September 2013