On the trail of the Blues

- Published

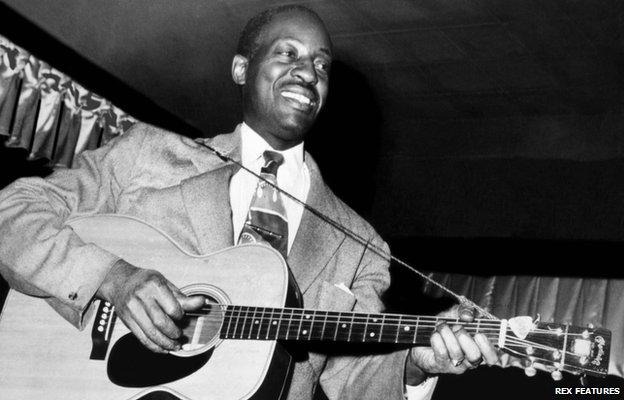

Before graduating to the guitar, bluesman Big Bill Broonzy improvised instruments including a cigar-box violin

Jeremy Marre recalls filming BBC Four documentary The Man Who Brought the Blues to Britain, on location in Arkansas.

Big Bill Broonzy was a giant of the blues world, a pioneer who, in 1920, escaped the racially-divided state of Arkansas for the city of Chicago.

From there, he travelled to Europe, influencing folk, jazz, and generations of rock musicians such as Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Ray Davies. But - strangely - none of them had any idea of who Big Bill really was.

On our voyage to unravel Broonzy's tangled private life and musical legacy, we flew to Arkansas, with no idea that we would shortly find ourselves in the embalming room of a mortuary in Main Street, North Little Rock.

Our first task was to find the legendary bluesman's grandnieces. Little Rock is where Bill first learned to play: "I made a fiddle out of a cigar box, and played for white people's picnics. A man told me: 'You're too good for playin' to Negroes'. White folks wanted all the good things for themselves."

We searched for his grandnieces down leafy streets flanked by morgues and churches. Competition for souls, in Little Rock, is fierce.

Broonzy's songs often depicted racial prejudice

Jo Ann and Rosie greeted us graciously; they're feisty, articulate ladies who recalled every detail of Uncle Bill's visits. "When he came home, he always had some woman with him. He'd always get the ladies' attention. I don't know if it was the guitar or his good looks."

Rosie gave a vivid account of the parties given in honour of Bill, and the dark spectre of racism that lay just beyond their windows: "Where my grandma lived, they burnt this big huge cross. The whole neighbourhood could see it. But Uncle Bill would always make it ok. He wasn't going to let anything happen to us."

Broonzy's songs often depicted the racial prejudice he and his family encountered:

If you're white, you're alright/If you're brown, stick around/But if you're black, oh brother/You gotta get back, get back, get back.

Rosie keeps a collection of Bill's albums together with some older, torn memorabilia: a certificate of his birth, and of his first marriage. But the dates didn't tally. Throughout his writings, fiction and fact are deftly inter-woven because often his words were metaphors or code for something better left unsaid.

That spring day in Little Rock was our last with Bob Riesman, our consultant. Bob is bearded and enthusiastic. He's also the world authority on Broonzy. And we needed to film the final part of his interview before his plane left, imminently, for Chicago.

He'd discussed the years when Broonzy was king of Chicago's all-black clubs while simultaneously playing Carnegie Hall to a white society audience hoping to see their first real-live Mississippi bluesman.

Bill wrote a song for that occasion called 'Just A Dream'. The audience thought it was so cute hearing Bill sing about a black man sitting in the White House, in the President's chair even. They laughed at its absurdity.

That was December 1938, just seventy years before Obama took his seat there. But in Broonzy's racially divided world, it was still 'Just A Dream'.

Closing prayer

We needed Riesman to reveal more about Bill's music before he left us. We set the camera on Rosie's porch, but every time Bob opened his mouth, an aircraft thundered overhead, a lawnmower started up or a wild dog howled. A neighbour, astride his twin-engine Honda, joked: "If it's peace you want, what y'all need is a morgue".

We drove all around North Little Rock in search of a quiet location. But it was Memorial Day Weekend and everything was closed. We tried the bars, churches and boarding houses. All locked. Our most pressing problem was Bob's plane, and Bob is risk averse. Which meant we became increasingly tetchy as the clock ticked slowly down on Main Street.

To every passer-by I'd call, with increasing desperation: "I need a room .. we're from the BBC .. a film on Big Bill Broonzy .. help us? Please?" Windows slammed.

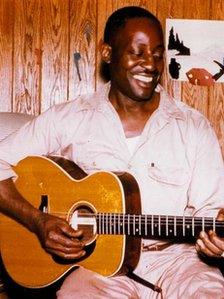

Broonzy died in Chicago in 1958

My last hit was a redbrick lawyer's office: Hardin and Grace, Experts in Real Estate and Litigation. A lady opened the door a crack and I recited my mantra. She asked: "That's Big Bill who?"

"Broonzy", I gasped.

"He wants to do an interview?"

"Broonzy's dead!"

Her eyes lit up. "I gotcha". She hurried off down a deep corridor.

Moments later a figure appeared from the gloom. He was small of stature, bald of head, white-bearded and with a shirt to match. He introduced himself not as Colonel Sanders but David A Grace, Attorney at Law. I repeated my lines with restrained panic. He eyed me sympathetically and whispered for me to follow him.

As I trod the dim corridor, I saw engraved above the doorways: Embalming Room (where the fluid of the dead are drained), and then what must have been the Refrigeration room, and next, the Viewing room (where bodies are washed and laid in coffins).

Finally he pulled open a heavy door that creaked like the soundtrack to a Hammer Horror film. I must admit I hesitated; and then I entered the room, astonished. The walls were hung with guitars and the shelves were crammed with books on bluesmen from every era. I'd entered the den of Big Bill's biggest, perhaps only, fan in Little Rock.

We did the interview with Bob in double time. And it ended with his recalling Barack Obama's inauguration as President, where Bill was invoked in a closing prayer: "That the day might come when black will not be asked to get back, when brown can stick around .. and when white will embrace what's right".

The Man Who Brought The Blues To Britain: Big Bill Broonzy is on BBC Four on Sunday 1 December at 21:00GMT